1

Y

EAR

T

WO

Second Language Acquisition

Academic Year 2011-2012

#18: Motivational factors and attributions

1. Defining motivation

By and large, the social-psychological construct of motivation is thought of as

an inner drive, impulse,

emotion, or desire that moves one to a particular action. In other words, it refers to "the choices people

make as to what experiences or goals they will approach or avoid, and the degree of effort they will

exert in that respect" (Brown 2007:168-169). However, when applied to language-learning situations,

motivation may be interpreted as "the attitudes and affective states that influence the degree of effort

that learners make to learn an L2" (Ellis 1997: 75). In the light of extensive research, it is believed to be

a key to learning (Crookes & Schmidt 1991). In fact, motivation appears to be the second strongest

predictor of success in the study of L2, after aptitude (Gass & Selinker 2008: 426; after Skehan 1989).

2. Motivation and human needs

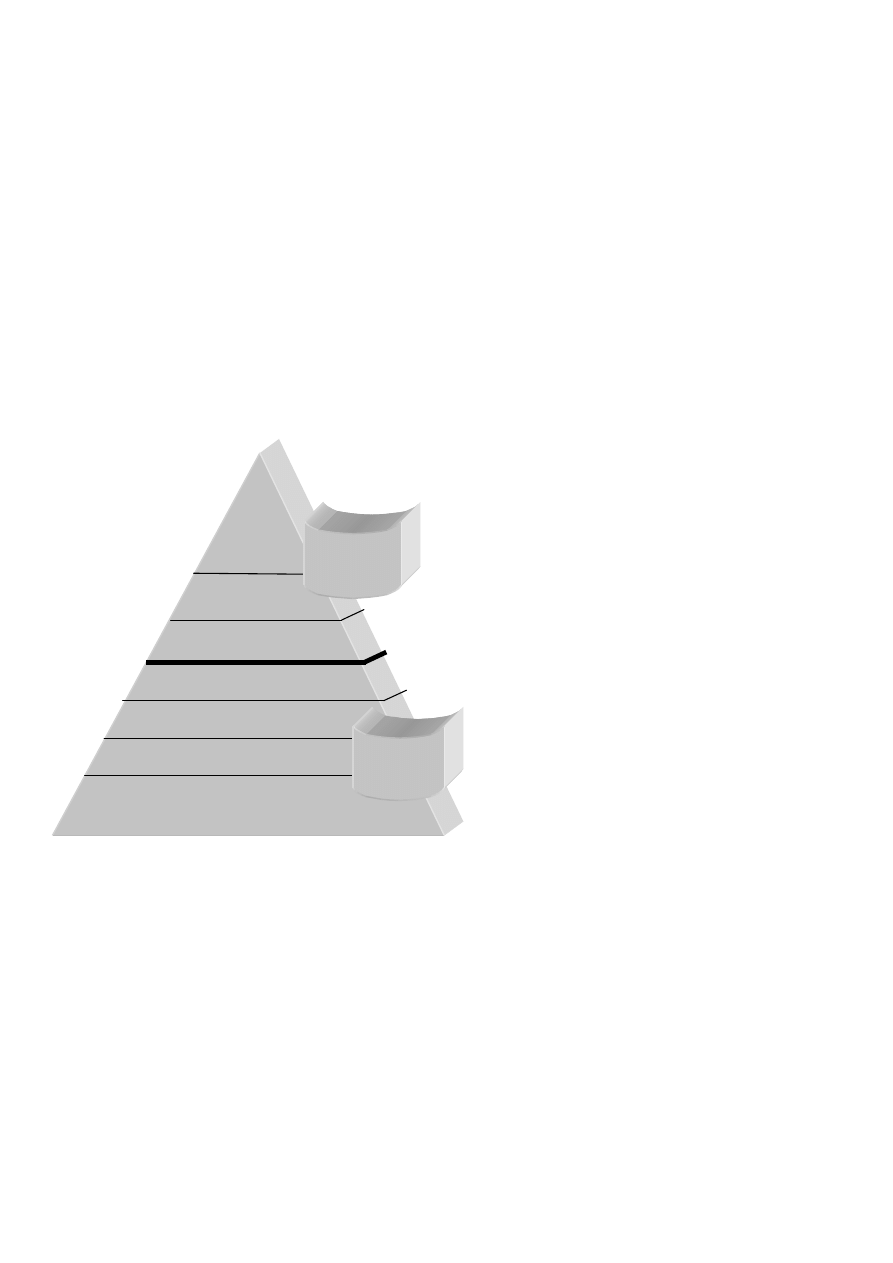

Fig. 1. Maslow's hierarchy of basic needs

(Salkind & Rasmussen 2008: 634)

Social psychologist Abraham Maslow (1970)

put forth the concept of a hierarchy of basic

human needs (cf. Fig. 1) which are believed

to account for motivation. The strata of

Maslow’s pyramid begin with

deficiency

needs, such as physiological necessities

(air, water, food), and then advance to

higher needs of security, identity, and self-

esteem, the fulfilment of which, in turn,

leads to

growth needs: from cognitive and

aesthetic needs to self-actualisation.

Other psychologists have acknowledged

further

fundamental

needs,

such

as

achievement, autonomy, affiliation, order,

change, endurance, aggression. Educational

psychologists,

for

example,

define

motivation in terms of certain

needs or

drives.

Cognitive

psychologist

David

Ausubel identified six such needs (Ausubel

et al. 1978: 368-379):

o

the need for

exploration, i.e. for seeing "the other side of the mountain", for probing the

unknown;

o

the need for

manipulation, i.e. for "operating" on the environment and causing change;

o

the need for

activity, i.e. for movement and exercise, both physical and mental;

o

the need for

stimulation, i.e. the need to be stimulated by the environment, by other people, or

by ideas, thoughts, and feelings;

S

ELF

-

A

CTUALI

-

SATION

A

ESTHETIC

N

EEDS

C

OGNITIVE

N

EEDS

E

STEEM

N

EEDS

B

ELONGINGNESS AND

L

OVE

N

EEDS

S

AFETY

N

EEDS

P

HYSIOLOGICAL

N

EEDS

G

ROWTH

N

EEDS

D

EFICIENCY

N

EEDS

2

o

the need for

knowledge, i.e. the need to process and internalise the results of exploration,

manipulation, activity, and stimulation, to resolve contradictions, to quest for solutions to

problems and for self-consistent systems of knowledge;

o

the need for

ego enhancement, i.e. for the self to be known and to be accepted and approved of

by others.

Brown (2007) believes that motivation, like self-esteem, can be viewed as global, situational, or task-

oriented. Learning a foreign language might require some of all three kinds of motivation. For example,

a learner may be highly "globally" motivated but his low "task" motivation may hinder his participation in

group activities or his written performance in L2.

3. Learner orientations - instrumental vs. integrative motivation

In the 1970s a significant tradition of motivational studies applied to L2 learning was developed in

Canada by Robert Gardner and his associates (cf. Gardner & Lambert 1972; Lambert 1972; Gardner &

MacIntyre 1991; MacIntyre & Gardner 1991; Gardner

et al. 1992), who proposed a distinction between

instrumental and integrative orientations of the L2 learner. Instrumental motivation refers to a need to

acquire a language as a way to achieve instrumental goals, such as pursuing a professional career,

reading literature in the field, translating, etc. Integrative motivation, on the other hand, is activated

when the learner wants to get integrated with the L2 speech community and culture - to identify himself

with and become a part of that social group.

However, more recent studies show that there is no single motivational factor determining the learning

of L2: certain learners in certain contexts may indeed profit from integrative orientation, while others in

different contexts may be more successful if they are instrumentally oriented. The findings also lend

support to the more and more widespread conviction that the two types of motivation are not

necessarily mutually exclusive. Second language learning is rarely stimulated by attitudes that are purely

instrumental or purely integrative. In most situations, the two types of motivation complement each

other.

4. Learner orientations - intrinsic vs. extrinsic motivation

Motivation is also typically examined in terms of the

intrinsic and extrinsic orientations of the learner.

Learners who study for their own self-perceived needs and goals are intrinsically oriented. In

contradistinction to the above type, those who pursue a goal exclusively to receive an external reward

from someone else are extrinsically motivated. Among typical extrinsic rewards are money, prizes, good

grades, and even certain types of positive feedback. Behaviours carried out solely to avoid punishment

are also extrinsically motivated, though punishment avoidance can also be viewed by some learners

intrinsically as a challenge that can enhance their sense of competence and self-determination.

However, the intrinsic-extrinsic construct must be differentiated from Gardner and Lambert’s

instrumental-integrative motivation. Although many instances of intrinsic motivation may indeed turn

out to be integrative, some may not. For example, a learner could, for highly developed intrinsic

purposes, want to learn L2 in order to progress in a career or to pursue an academic programme.

Similarly, another learner might adopt a positive

attitude toward the second language speech

community for extrinsic reasons: parental reinforcement, teacher’s encouragement, etc.

3

5. The motivational grid

Brown (2007: 175) plotted the relationship between the two above-mentioned dichotomies on the

following diagrammatic representation:

Motivational Taxonomy

INTRINSIC

EXTRINSIC

INTEGRATIVE

A L2 learner wishes to integrate

with the L2 culture (e.g., for

immigration or marriage)

Someone else wishes the L2 learner to know the

L2 for integrative reasons (e.g., Japanese-

American parents send their children to a

Japanese language school)

INSTRUMENTAL

A L2 learner wishes to achieve

goals utilising L2 (e.g., for a

career)

An external power wants the L2 learner to learn

L2 (e.g., a corporation sends a Japanese

businessman to the U.S. for language training)

6. Resultative motivation

Various other kinds of motivation have also been identified. One of the most interesting concepts is

resultative motivation. It is described by Ellis (1997) in the following words (pp. 75-76):

An assumption of […] research […] is that motivation is the

cause of L2 achievement. However, it

is also possible that motivation is the

result of learning. That is, learners who experience success

in learning may become more, or in some contexts, less motivated to learn. This helps to explain

the conflicting research results. In a context like Canada, success in learning French may

intensify English-speaking learners' liking for French culture. However, in California success in

learning English may bring Mexican women into situations where they experience discrimination

and thus reduce their appreciation of American culture.

7. Attribution theory

Alongside emotional security, a language student needs to develop a positive attitude to himself as a

learner. According to attribution theory, which studies causes that learners assign their success or

failure to, behind one's performance in L2 there are factors within one's control as well as those beyond

one's control. By and large, attribution theory shows how people make causal explanations and what

responses to questions beginning with 'why' are given. It accounts for the behavioral and emotional

consequences of those explanations. As Weiner (1984) states, achievement behavior may be influenced

by a task's objective qualities and to a considerable extent by an individual's attribute responsibility for

success on the task.

Psychologists believe that when learners feel that their performance is determined by factors which they

can control - such as their own efforts or abilities - they will show achievement behavior and respond

positively to failure, trying harder next time. On the other hand, when they are convinced that their

output is determined by factors outside their control - such as luck or the task’s difficulty - they may

respond negatively to failure and give up altogether, believing that they will not succeed, however hard

they may try.

4

Attribution theory originated in the 1950s and 1960s as one of the approaches to the study of

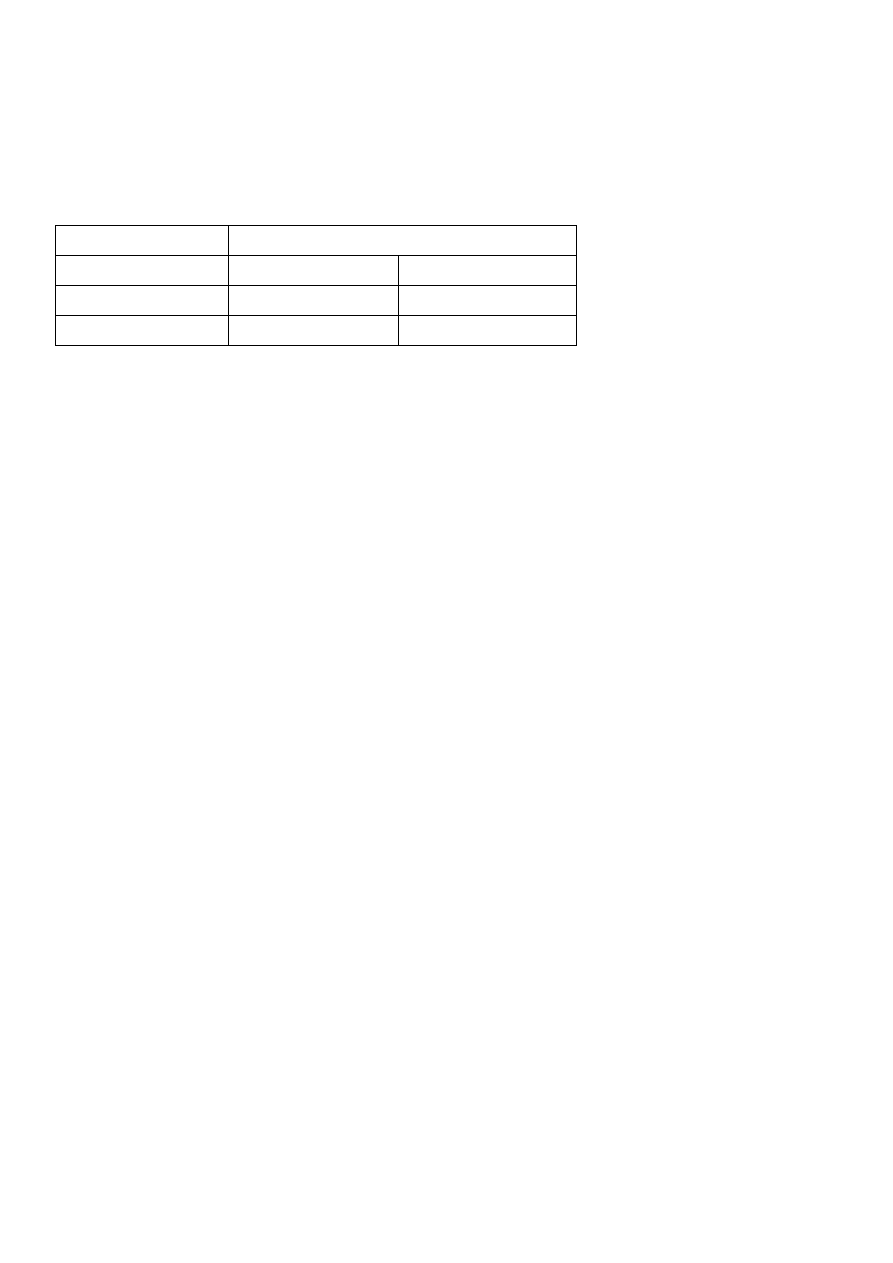

motivation. It suggests that people vary in the way they attribute causes to events. The four principal

determinants of success are:

ability, task difficulty, effort, and luck. These are analyzed in terms of

stability and locus of control (see the table below; after Skehan 1989: 51). The former two are relatively

unchangeable and are therefore in the stability dimension. In contrast, the latter two are unstable and

they are subject to modification.

LOCUS OF CONTROL

STABILITY

Internal

External

Stable

Ability

Task difficulty

Unstable

Effort

Luck

Graham (1994) adds further traditional attributions: mood, family background and help or hindrance

from others.

For the learning/teaching context, the worst situation obtains when individuals "consistently attribute

bad outcomes to stable internal attributes, and good outcomes to unstable external causes" (Skehan

1989: 52) - in other words, when they are convinced that their failure is due to their lack of ability.

Clearly, for language learning it is essential to what a student ascribes his or her achievement. If the

unstable factors, for example effort, are believed to be the causes of success, the motivation tends to

be higher. Learners who think that they have succeeded thanks to effort which they have invested are

usually more persistent and motivated, since they perceive themselves as having some bearing on the

learning process.

According to Dőrnyei (2001), there are two reasons why attribution theory is relevant for the study of

language learning. Firstly

, the feeling of failure in learning an L2 is very common: most learners are not

fully satisfied with their level of L2 and they typically fail in at least one L2 during their lifetime.

Secondly, a lot - and quite rightly so - can be attributed to linguistic aptitude. As Covington (1998)

states, "it is not so much the event of failure that disrupts academic achievement as it is the meaning of

failure. Thus, rather than minimizing failure, educators should arrange schooling so that falling short of

one's goals will be interpreted in ways that promote the will to learn". Additionally, promoting effort

attributions is important. Teachers should stress the role of effort and make students believe that it can

lead to success, but they should not lay emphasis on ability because, unlike effort, it does not offer

everyone en equal chance.

8. Locus of control

Locus of control […] is a personality dimension which can be presented as a continuum from

external to internal control over life events […]. [It] is not objectively but subjectively

determined, i.e. people perceive life events not as they really are but according to environmental

circumstances. In other words, life events can be either caused by our own actions (internal

control) or by the environment, i.e. other people, God, luck, fate etc. (external control). […] It is

assumed that people with more internal control are better prepared to guide their individual

development and their assimilation with the environment. Consequently, they appear to be more

ambitious and more academically gifted. On the other hand, too much internal control may

result in individuals blaming themselves for all negative events which were, in fact, caused by

5

other people. Individuals with external locus of control are more conformist, submissive, less

ambitious, more dependent on others, and generally less gifted academically. (Michońska-

Stadnik 2006: 147-148)

The process of change of the locus of control from the external to the internal world is called

regulation. During those periods when the child is most controlled by another person, he or she

is considered to be other-regulated, and upon the attainment of the ability to function

independently in the task, he or she is considered to be self-regulated. (Buckwalter 2001:

382)

9. Ways of encouraging language learners

Dőrnyei (2001) suggests some means of encouraging foreign-language students:

o

Providing feedback on effort: feedback that teachers give to their students is the most

convincing means towards promoting effort attributions. If students fail, teachers should

underline the low effort and communicate to students that they can do better in the future, but

if students fail in spite of the fact that they put effort into their work, teachers should explain

that effort has to be complemented with sufficient skills and strategies.

o

Refusing to accept ability attributions: teachers should not pay attention to ability and when

students assess their attributions to low ability, e.g. 'I'm not good at languages', teachers should

make it clear that they are convinced about their abilities.

o

Modeling effort-outcome linkages: teachers may talk about their personal experiences how they

managed to do a difficult task by putting a lot of effort to succeed. They can also encourage

learners to offer effort explanations: by giving suitable prompting and support. For instance,

teachers may ask learners what they found thought-provoking about a language task, what they

have found out from the experience.

o

Making effort and perseverance a class norm: teachers should make remarks such as 'I like the

way you try' or 'That was a nice piece of effort' and underline the significance of effortful

behaviour. This should be made classroom norm. Strategic effort attributions help learners to

believe that working hard in a particular way is what leads to success. Teachers can encourage

them to view failures as problem solving situations in which the search for an improved strategy

becomes their main focus of attention.

REFERENCES AND SUGGESTIONS FOR FURTHER READING

Ausubel, D. A., Novak, J. D. & Hanesian, H. 1978.

Educational Psychology. A Cognitive View. Second

Edition. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Brown, H. D. 2007.

Principles of Language Learning and Teaching. Fifth Edition. Englewood Cliffs, NJ:

Prentice Hall Regents.

Buckwalter, P. 2001. "Repair sequences in Spanish L2 dyadic discourse: A descriptive study".

Modern

Language Journal 85/3: 380-397.

6

Covington, M. V. 1998.

The Will to learn: A Guide for Motivating Young People. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Crookes, G. & R. Schmidt, W. 1991. "Motivation: Reopening the research agenda".

Language Learning 41:

469-512.

Dörnyei, Z. 1994. “Understanding L2 motivation: On with the challenge!”

The Modern Language Journal

78/4: 515-523.

Dőrnyei, Z. 2001.

Attitudes, Orientations, and Motivations in Language Learning: Advances in Theory,

Research, and Applications. Nottingham: University in Nottingham.

Dörnyei, Z. 2005.

The Psychology of the Language Learner. Individual Differences in Second Language

Acquisition. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Ellis, R. 1997.

Second Language Acquisition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gardner, R. C. & Lambert, W. E. 1972.

Attitudes and Motivation in Second Language Learning. Rowley,

MA: Newbury House Publishers.

Gardner, R. C. & MacIntyre, P. D. 1991. "An instrumental motivation in language study: Who says it isn’t

effective?"

Studies in Second Language Acquisition 13: 57-72.

Gardner, R. C., Day, J. B. & MacIntyre, P. D. 1992. ‘Integrative motivation, induced anxiety, and language

learning in a controlled environment.’

Studies in Second Language Acquisition 14: 197-214.

Gass, S. M. & Selinker, L. 2008.

Second Language Acquisition. An Introductory Course. Third Edition.

New York: Routledge.

Graham, S. 1994. "Classroom motivation from an attributional perspective". In O’Neil, Jr, H. F. & M.

Drillings (Eds.),

Motivation: Theory and Research. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence: Erlbaum, 31-48.

Lambert, W. E. 1972.

Language, Psychology, and Culture: Essays by Wallace E. Lambert. Stanford, CA:

Stanford University Press.

MacIntyre, P. D. & Gardner, R. C. 1991. "Language anxiety: Its relationship to other anxieties and to

processing in native and second languages".

Language Learning 41: 513-534.

Maslow, A. H. 1970.

Motivation and Personality. Second Edition. New York: Harper & Row.

Michońska-Stadnik, A. 2006. "Some aspects of environmental and gender constraints on attributions of

second language learners". In Zybert, J. (Ed.),

Issues in Foreign Language Learning and Teaching.

Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego. 147-160.

Salkind, N. J. & Rasmussen, K. (Eds.), 2008.

Encyclopedia of Educational Psychology. Thousand Oaks, CA:

Sage.

Skehan, P. 1989.

Individual Differences in Second-Language Learning. London: Arnold.

Weiner, B. 1984. "Principles for a theory of a student motivation and their application within an

attributional framework". In R. Ames and C. Ames (Eds.),

Research on Motivation in Education:

Student Motivation (Vol.I). San Diego: Academic Press. 15-38.

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Konspekt prezentacji #18 Motivational Factors & Attributions

Year II SLA #16 Neurolinguistic Factors

Year II SLA #11 Gender

Year II SLA #5 The Contrastive Analysis Hypothesis

Year II SLA #7 Error Analysis & Interlanguage

Year II SLA #17 Learning Strategies & Ambiguity Tolerance(1)

Year II SLA #3 Theories of First Language Acquisition

Year II SLA #19 Language Anxiety, Classroom Dynamics & Learner Beliefs

Year II SLA #2 First Language Acquisition

Year II SLA #6 The Significance of Learners Errors

Dramat rok II semsetr I English literature year II drama sample questions

Budownictwo Ogolne II wyklad 18 sc dzial (2)

18 SOŁŻENICYN ALEKSANDER DWIEŚCIE LAT RAZEM CZĘŚĆ II ROZDZIAŁ 18 W LATACH DWUDZIESTYCH

Arnold Rossetti study questions year II

II DWK 18 Preludium i fuga gis moll nr 18 BWV 887

akumulator do mazda 6 ii gh 18 mrz 20 mrz 25 mrz

akumulator do toyota rav 4 ii xa2 18 vvti 20 vvti 4wd 24 vvti

akumulator do volkswagen jetta ii 19e 18 18 t 18 16v 18 sy

więcej podobnych podstron