Zbigniew TURLEJ

Electrotechnical Institute

Efficiency and colors in LEDs light sources

Abstract. The light gains from LEDs continue to grow, doubling a about every two years. It gives real hope for the LEDs solving problem of

efficiency in the lighting. This paper presents review some problems connected with efficiency and colors inorganic LEDs technologies, also gives

some new perspectives for development based on organic LED and plasmonics.

Streszczenie. Światło emitowane przez źródła LED podwaja swą skuteczność świetlną co dwa lata. To stwarza poważną nadzieje na rozwiązanie

problemu efektywności energetycznej w oświetleniu. W referacie zarysowano historię i perspektywy rozwoju efektywności i barwy w technologii LED

ze szczególnym uwzględnieniem materiałów nieorganicznych, organicznych i efektów plazmoniki. (Barwy i efektywność źródeł światła LED).

Keywords: energy efficiency, LED colors and technology, light and health, illuminating technology.

Słowa kluczowe: efektywność energetyczna, barwa i technologie LED, światło i zdrowie, technika świetlna.

Lighting and energy efficiency

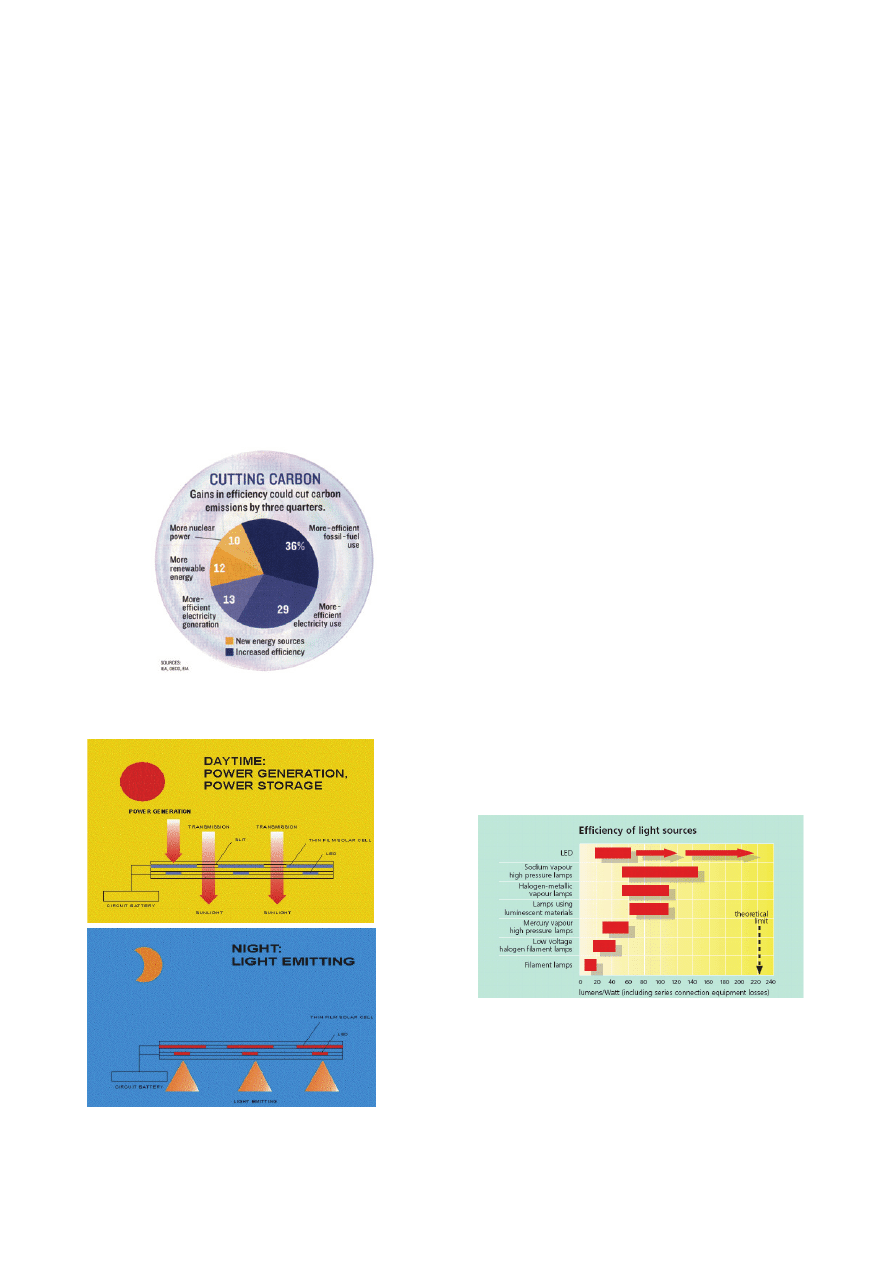

Population and economic growth threaten to keep

energy demand and carbon emissions growing, too. But the

new long-range forecasts (fig.1) produced by energy

experts show that in many key areas, increased efficiency

offers real hope for solving the problem.

Fig.1. The increasing efficiency offers the cutting carbon emissions

[1]

Fig.2. The integration of LEDs with photovoltaic (PV) and

architectural transparent materials

Lighting gobbles up 20% of the world’s electricity, or the

equivalent of roughly 600.000 tons of coal a day. Forty

percent of that powers old-fashioned incandescent light

bulbs – a 19

th

-century technology that wastes most of the

power it consumes on unwanted heat. Light emitting diode

(LED) lamps, not only use less electricity then incandescent

bulbs to generate the same amount of light, but they also

last 50 times longer. In December 2006, Dutch electronic

firm Philips became the first major bulb manufactures to

announce a gradual phase out of the production of

incandescent bulbs. Now exist an opportunity to have

lighting systems that modulate their intensity to supplement

natural light. These systems will require the integration of

LEDs with photovoltaic (PV) and architectural transparent

materials (fig.2).

The unique properties

Light sources should be as small as possible, produce

light efficiently and have a long life. Until now, however, no

filament or discharge lamp has combined all three

properties. Only light emitting diodes (LEDs) achieves this.

No other lamp possesses comparably small dimensions.

The miniature form requires small optical systems and

creates new demands for light guidance. The light optical

systems are mode from synthetic materials with light

refractive indices and replace the classic metal reflector.

The light gains from light diodes continue to grow, doubling

about every two years. It is not unrealistic to assume that in

ten to fifteen years LEDs will become the most efficient light

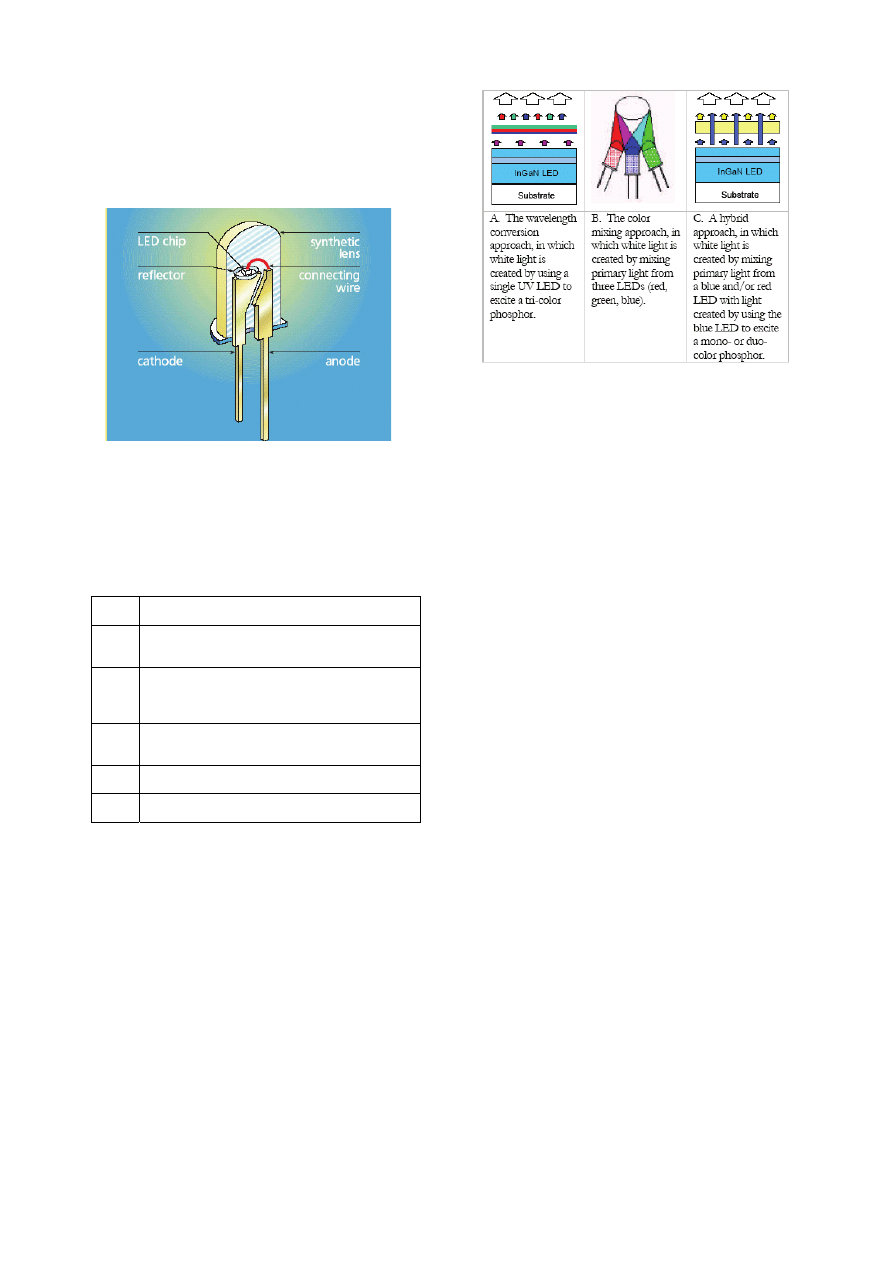

sources (fig. 3).

Fig.3. The light yield from LEDs is reaching ever higher vales [2]

With 50.000 operational hours light diodes have a very

long life. This results in a new conceptual approach to the

design and development of lighting. There is no longer a

need for equipment for changing the light source. LEDs and

luminaire grow old jointly and both are changed together

when the lamp has reached the end of its lifespan.

PRZEGLĄD ELEKTROTECHNICZNY - KONFERENCJE, ISSN 1731-6106, R. 5 NR 1/2007

55

The light production

In conventional lamps visible light arises as a by-product

of the warming of metal helix, or by a gas discharge or by

the conversion of a proportion of the ultraviolet radiation

produced in such a discharge. In light diodes the production

of light takes place in a semiconductor crystal which is

electrically excited to elektroluminescence (fig. 4, table 1).

Fig.4. LED functional principles. The light comes from

semiconductor crystal (LED chip). It is electrically excited to

produce light: two areas exist within the crystal, a n- conducting

area with a surplus of electrons and a p- conducting area with a

deficit of electrons. In the transitional area, called pn- transition or

depletion layer, light is produced in a recombination process of the

electron with the atom with the deficit of an electron when current is

applied to the crystal [2].

Table 1. History of light production by LED

1907

Henry Joseph Round (1881- 1966) discovers the

physical effect of elektroluminescence.

1962

The first red luminescent diode of type GaAsP

comes onto the market. The industrially produced

LED is barn.

1971

From the beginning of the seventies LEDs are

available in further colours: green, orange, yellow.

Performance and effectiveness is continually being

improved in all LEDs.

1980s to early 1990s High performance LEDs (LED

modules) in red, later red/orange, yellow and

green become available.

1995 The first LED producing white light by

luminescence conversion is introduced.

1997

White LEDs come onto the market.

As protection against environmental influences the

semiconductor crystal is set into a housing. This is

constructed so that the light radiates in a semicircle of

almost 180 degrees. Guidance of the light is thus easier

then in filament or discharge lamps, which generally radiate

light in all directions.

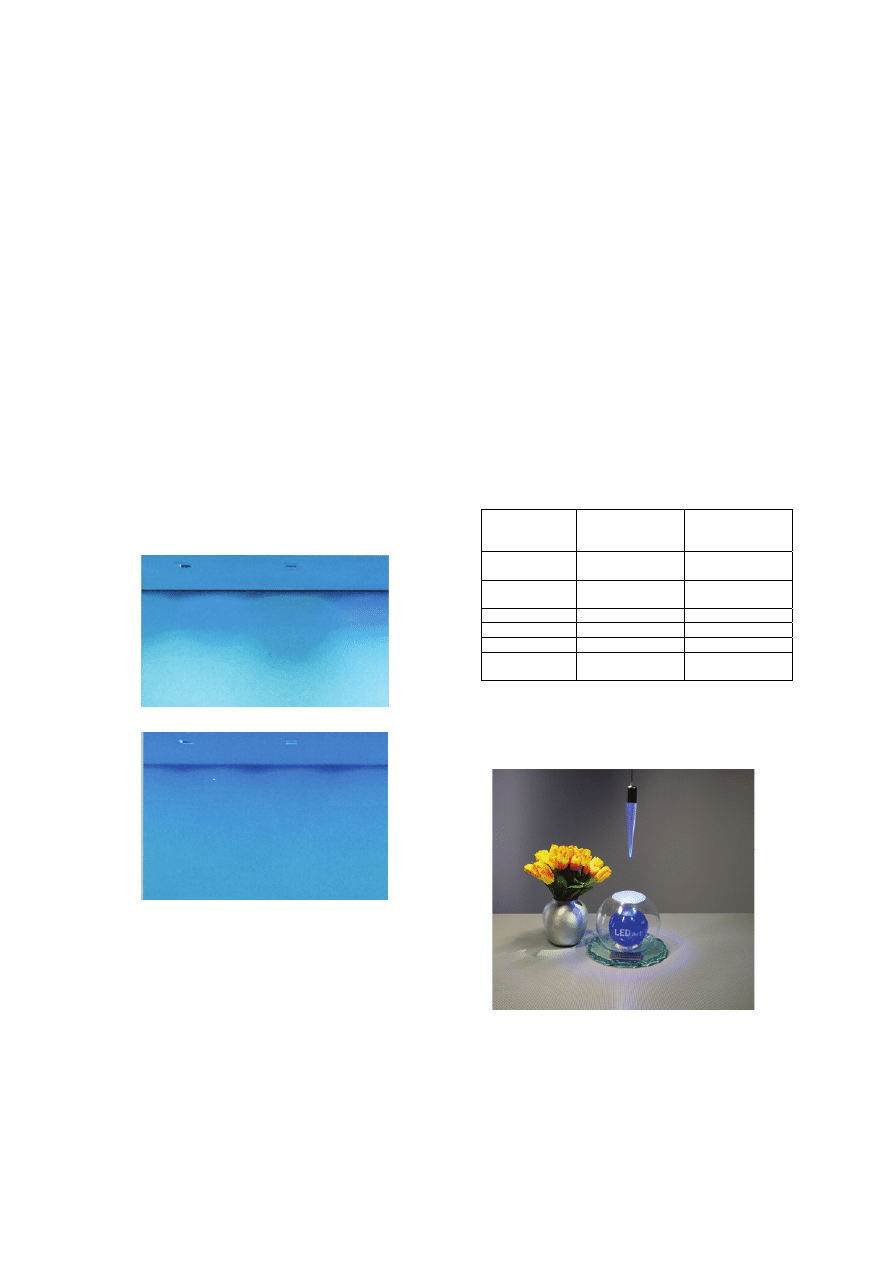

The monochromatic and the white colores

According to the type and composition of the

semiconductor crystal the light diode has different

monochromatic colors. Today there are blue, green, yellow,

orange, red and amber, together with nuances of these

colors. The white light can be generated by three general

approaches, illustrated in figure 5. The first is the

wavelength-conversion approach; the second is

the color

mixing approach; and the third is a hybrid between

the two.

Fig.5. The three possible approaches to white-light production [3]

Wavelength Conversion Approach

The first approach for transforming narrowband

emission into broadband white light involves using UV LEDs

to excite phosphors that emit light at down-converted

wavelengths. In general, this approach is likely to be the

lowest cost, because of its low system complexity (only a

single LED chip, and since the colors are created already

blended, lamp-level optical and color engineering is

minimized). It is also likely to be the least efficient, because

of the power-conversion loss associated with the

wavelength down-conversion; and the least flexible, since

the colors are “preset” at the factory.

Hence, a general challenge will be the development of UV

(340-380 nm) LEDs with high (>70%) external power-

conversion efficiency and input power density, and

multicolor phosphor blends with high (>85%) quantum

efficiency.

Color Mixing Approach

The second approach for transforming narrowband

emission into broadband white light is to combine light from

multiple LEDs of different colors. In general, this approach

is likely to be the most efficient, as there are no power-

conversion losses associated with wavelength down-

conversion. It is also likely to be the most flexible, since the

hue of the

light can be controlled by varying the mix of

primary colors, either in the lamp, or in the luminaire.

However, it is also likely to be the most expensive, because

of its high system complexity (multiple LED chips, mixing of

light from separate sources, and drive electronics that must

accommodate differences in voltage, luminous output,

element life and thermal characteristics among the

individual LEDs). Hence, a general challenge will be the

development of red, green and blue LEDs with high (>50%)

external power-conversion efficiencies and input power

density, and low-cost optics and control strategies for

spatially uniform, programmable color-mixing either in the

lamp or in the luminaire.

Hybrid Approach

The third approach for transforming narrowband

emission into broadband white light is a hybrid approach.

The present generation of white LEDs, with luminous

efficacies of 25

lm/W, is based on this approach. Primary

light from a blue (460 nm) InGaN-based LED is mixed with

blue-LED-excited secondary light from a pale-yellow

YAG:Ce

3+

-based inorganic phosphor. The secondary light is

centred at about 580 nm with a full-width-at-half-maximum

PRZEGLĄD ELEKTROTECHNICZNY - KONFERENCJE, ISSN 1731-6106, R. 5 NR 1/2007

56

line width of 160 nm. The combination of partially

transmitted blue and reemitted yellow light gives the

appearance of white light at a color temperature of 8000 K

and a luminous efficacy of about 25 lm/W. This combination

of colors is similar to that used in black-and-white television

screens – for which a low-quality white intended for “direct”

rather than “indirect” viewing – is acceptable. Other

variations of this approach are possible. The simplest

extension would be to mix blue LED light with light from a

blue-LED excited green and red duo-color phosphor

blend25 – this variation is likely to be give the best balance

between efficiency, color quality, cost and system

complexity. A more complex but perhaps more efficient

extension of this approach would be to mix blue and red

LED light with light from a blue-LED excited green

phosphor. In general, this approach is intermediate

amongst the three approaches in efficiency, complexity and

cost. It is likely to be intermediate in efficiency, as power-

conversion losses from wavelength down-conversion are

less from the blue than from the UV, but still greater than no

power-conversion losses. It is likely to be intermediate in

cost and system complexity, as only one (or at most two)

LEDs is used, but light from the LED must still be color-

mixed with light from the phosphor. Hence, a general

challenge will be the development of blue LEDs with high

(>60%) external power-conversion efficiencies and input

power density, blue-excitable duocolor phosphor blends

with high (>80%) quantum efficiency, and low-cost optics for

spatially uniform color-mixing in the lamp.

a)

b)

Fig. 6. The human eye registers even the slightest deviation in hue

(a) such as coloured wall washing (b) [2]

Problems with colors

One of the key characteristics of LEDs is their light color

saturation. Because of the manufacturing process we con

have deviations in the light colors of two of same LED

modules. The human eye registers even the slightest

deviation in hue (fig.6). Semiconductor producers classify

each LED into different categories, known as “binnings”

using the values actually measured. But even with the most

stringent selection, deviations still have to be accepted. To

ensure consistent colour Erco has introduced a

colour

compensation system. Every colour compensated LED

modules is individually measured and adjusted in the

factory. The compensation factors are permanently stored

in the control gear.

Blue LED and health

Circadian phototransduction is a term used to describe

how the retina converts light into neural signals that

regulate rhythms such as sleep, body temperature and

hormone production, and has been a topic of interest in

many laboratories around the world. We now know that the

circadian system is maximally sensitive to short-wavelength

light and that a combination of classical photoreceptors and

newly-discovered retinal neurons, which respond directly to

light exposure (called intrinsically-photosensitive retinal

ganglion cells or ipRGCs), participate in circadian

phototransduction. Much of what we do in lighting rests

upon a quantitative foundation for the specification of light

sources and light levels for vision. The model of circadian

phototransduction is the first attempt to establish a parallel

foundation for the circadian system. Much like we want to

know many lumens per watt a light source produces for the

visual system, it is now possible to calculate circadian

stimulus per watt. Table 2 shows values of circadian

stimulus per watt for several commercially available light

sources.

Table 2. Photopic lumens per watt and circadian stimulus per watt

for various light sources [3]

As we can see in Table 2 the blue LED light source (470

nm) is the most effective in suppressing melatonin than

others. Figure 7 shows the fixture for a melatonin regulation

in workplace.

Fig.7. The blue LED (470 nm) fixture for a effect melatonin

regulation in workplace designed by Electrotechnical Institute [4]

Looking a long way into the future, it is easy to imagine

that new standards will be adopted, new light sources

circadian systems, we may all end up in a healthier built

environment.

Light source

Photopic

lumens/watt

Circadian

stimulus/watt

Fluorescent

3000K

100 lm/W

74 CS/W

Fluorescent

7500K

100 lm/W

157 CS/W

Incandescent

12 lm/W

12 CS/W

D65

70 lm/W

133 CS/W

Clear Mercury

45 lm/W

18 CS/W

Blue LED

(470nm)

8 lm/W

15 lm/W

223 CS/W

418 CS/W

PRZEGLĄD ELEKTROTECHNICZNY - KONFERENCJE, ISSN 1731-6106, R. 5 NR 1/2007

57

LEDs - the new horizons

Korean company has released a single-die white

inorganic LED that can emit up to 240 lm at its maximum

drive current of 1A. The new P4 emitter is also claimed to

offer the word’s highest luminous efficacy, coming at 100

lm/W at 350 mA drive current that is required for general

illumination applications. Company says that the high

luminosity was reached through its proprietary phosphor

and packaging techniques, and further improvements are in

the pipeline. A 135 lm/W source is due to emerge this year,

and more incremental improvements are expected to lead

to 145 lm/W performance early in 2008.

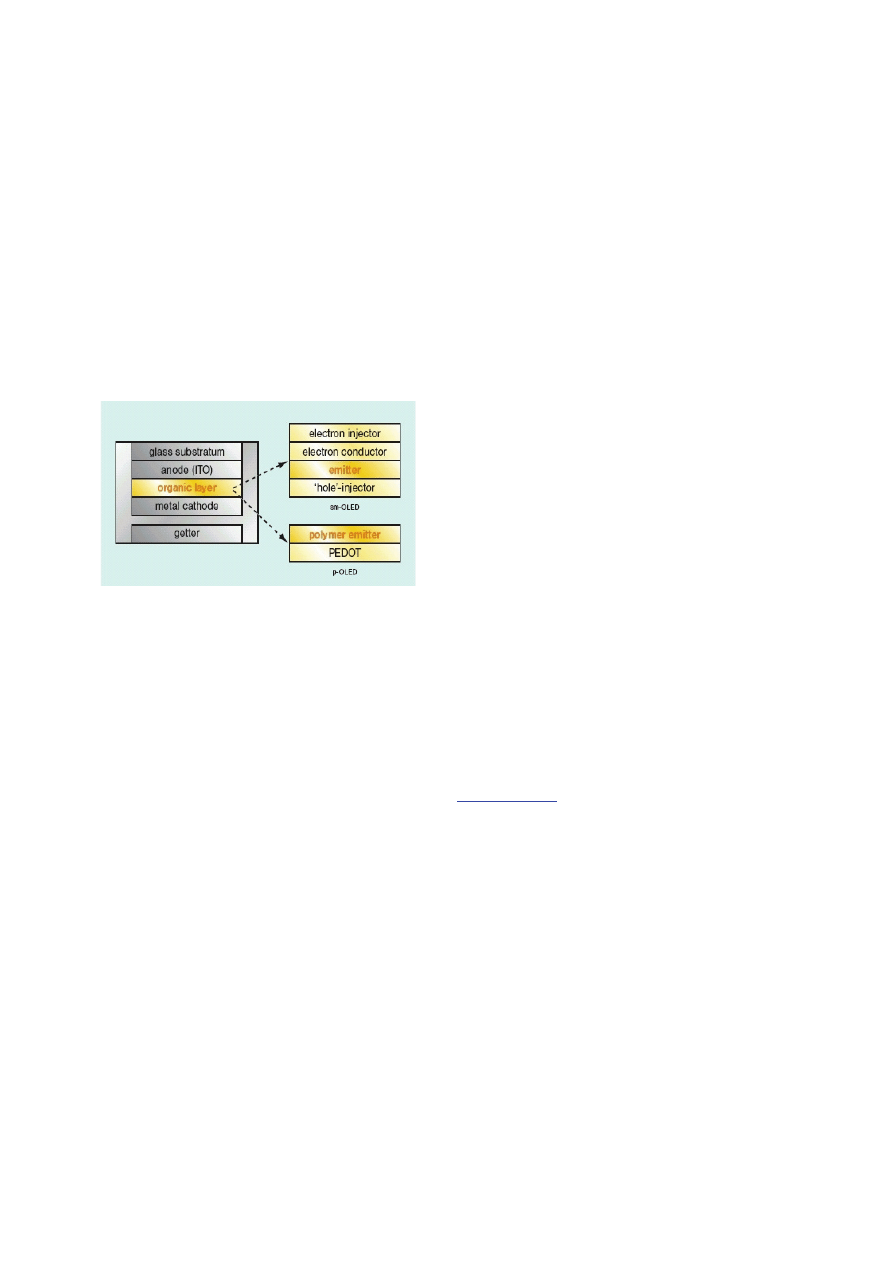

Another

revolutionary means of lighting for the future is organic

LEDs (OLEDs).Today they illuminate displays, but they will

soon open up other types of lighting. Research on materials

has discovered a series of systems in which light can be

produced. The results reveal two groups: sm-OLEDs with

small molecules and p-OLEDs with polymers. They are

mainly differentiated by the number of materials necessary

to construct the light producing layers (fig 8).

Fig.8. Schematic representation of the functional principles of

OLEDs – the organic layer of sm-OLEDs consists of four coatings.

The same functionality can be achieved in p-OLEDs with two

coatings [5].

Using a method of light mixture in this organic layers,

white and colored OLEDs which are completely transparent

when switched off, can be manufactured. The production of

these is simple but their light can, however, only be dimmed

and not changed in color. The mixture for white light makes

it possible to adjust color temperature because distinct

organic layers are used to produce the three basic colors.

Such solutions hence offer possibilities for the design of

color sequences. Alternatively white light can be produced

with the aid of conversion principle, exactly as with

inorganic LEDs. If white OLEDs, which are constructed in

this way, then the light source is not transparent when

switched off. OLEDs, which are constructed from single,

individually controllable points, offer maximum flexibility in

the production of color and in dimming, however at very

high cost. In future solutions to this problem information

could, for example, be presented on illuminating surfaces.

Recently, however, scientist have been working on a new

technique for transmitting light through nanoscale interface

structures made of a metal and a dielectric. Under the right

circumstances, we have a resonant interaction between the

waves and the mobile electrons at the surface of the metal.

The result is the generation of surface plasmons – density

waves of electrons that propagate along the interface like

the ripples that spread across the surface of a pond after

you throw a stone into the water. Plasmonic materials may

revolutionize the lighting industry by making LEDs brighter.

It has become evident that this type of field enhancement

can also dramatically raise the emissions rates of dots and

quantum wells – tiny semiconductors structures that absorb

and emit light – thus increasing the efficiency and

brightness of solid-state LEDs. In 2004 at Japan’s Nichia

Corporation was demonstration that coating the surface of a

gallium nitride LED with dense arrays of plasmonic

nanoparticles (made of silver, gold or aluminum) could

increase intensity of the emitted light 14-fold.

REFERENCES

[ 1 ] G l a i n S . , K a s h i w a g i A . , K r o v a t i n Q ., Seeing the

scenarios, Davos Special Report, Newsweek, (2007), n.4, 44-

45,

[2] LED – Light from the Light Emitting Diode, Fördergemeinschaft

Gute Licht, (2006)

[3] Light Emitting Diodes (LEDs) for General Illumination, OIDA,

(2002)

[ 4 ] T u r l e j Z., Czynnik hormonalny w oświetleniu wnętrza, Prace

Instytutu Elektrotechniki, (2006), n.228, 297-306

[5] Briefings, Lighting, (2007), n.2, 8-14

[ 6 ] A t w a t e r H., The Promise of Plasmonics, Scientific American,

(2007), n.4, 38-45,

[7] F i g u e r o M., Research matters, LD+A, (2006), n.5, 24-26,

[8] S c h i e l k e T., Color compensation: ERCO technology for trude-

color varychrome LED luminaires, ERCO Leuchten GmbH, (2006),

25

_____________________

Author: dr inż. Turlej Zbigniew, Electrotechnical Institute,

Pożaryskiego 28, 04-703 Warsaw, Poland, e-mail:

PRZEGLĄD ELEKTROTECHNICZNY - KONFERENCJE, ISSN 1731-6106, R. 5 NR 1/2007

58

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Emissions and Economic Analysis of Ground Source Heat Pumps in Wisconsin

Masonry and its Symbols in the Light of Thinking and Destiny by Harold Waldwin Percival

How effective are energy efficiency and renewable energy in curbing CO2 emissions in the long run A

Kołodziejczyk, Ewa Literature as a Source of Knowledge Polish Colonization of the United Kingdom in

Degradable Polymers and Plastics in Landfill Sites

Estimation of Dietary Pb and Cd Intake from Pb and Cd in blood and urine

Aftershock Protect Yourself and Profit in the Next Global Financial Meltdown

General Government Expenditure and Revenue in 2005 tcm90 41888

A Guide to the Law and Courts in the Empire

D Stuart Ritual and History in the Stucco Inscription from Temple XIX at Palenque

Exile and Pain In Three Elegiac Poems

A picnic table is a project you?n buy all the material for and build in a?y

Economic and Political?velopment in Zimbabwe

Power Structure and Propoganda in Communist China

A Surgical Safety Checklist to Reduce Morbidity and Mortality in a Global Population

VENTILATION AND COOLING IN UNDERGROUND MINES (2)

VENTILATION AND COOLING IN UNDERGROUND MINES

więcej podobnych podstron