Explaining the first

language acquisition

● The behaviourists: ‘you say what I

say’

● The innatists: ‘it’s all in your mind’

● The interactionists: ‘it’s from both

inside and outside

Classification of Language

Acquisition Theories Around

“Nurture and Nature Distinction”

THEORIES BASED ON "NURTURE"(environmental

factors are believed to be more dominant in

language acquisition)

- Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal

Development

- Skinner’s Verbal Behavior

- Piaget’s View of Language

Acquisition

Classification of Language

Acquisition Theories Around

“Nurture and Nature Distinction”

- The Competition Model (E. Bates)

- The Speech Act Theory

- The Acculturation Model

Classification of Language

Acquisition Theories Around

“Nurture and Nature Distinction”

-

Accommodation Theory

- The Interactionist View of

Language Acquisition

- The Connectionist Model

Classification of Language

Acquisition Theories Around

“Nurture and Nature Distinction”

THEORIES BASED ON

“NATURE”(innate factors are

believed to be more dominant in

language acquisition)

- A Neurofunctional Theory of

Language Acquisition

- The Universal Grammar Theory

- Fodor’s Modular Approach

Behaviourism

A theory of learning, most

influential in 1940s and 1950s, that

assumed people learn by imitation

and repetition. They are

encouraged to imitate through

consistent „positive reinforcement”

until habits are formed.

Behaviourists’ views on learning

the first language

Children imitate and practise the language

produced around them

The imitation is reinforced through

parents’ praise or successful

communication

Habits of „correct” language use are

formed

The quality and quantity of the language

the child hears as well as the consistency

and the intensity of the reinforcement

influence the child’s language behaviour.

B.F. Skinner (1957) Verbal behaviour

Behaviourists’ views on learning

the first language

Imitation:

Word for word repetition of all or

part of someone else’s utterance:

e.g.

Mum: „Shall we play with the puffer

train?”

Child: „Play with puffer train! Puffer

train!”

Behaviourists’ views on learning

the first language

Practice:

repetitive manipulation of form:

e.g.

Mum: „See, puffer trains have

wheels.”

Child: „Puffer train have wheels.

And car have wheels. They both

have wheels.”

Behaviourists’ views on learning

the first language

30% - 40% of children’s speech are

imitations of what someone has just said

Children imitate words and structures that

are just beginning to appear in their

speech

The imitation is structured (methodical)

The choice of what to imitate is based on

sth. new they have just begun to

understand and use.

Behaviourists’ views on learning

the first language

Points to consider:

- How do children choose what to

„practise”?

- How do children know how to

practise?

- Why do children who imitate less (by

20%) develop at the same rate?

- Why are children creative using

language?

Examples of children’s creativity

in language use

Patterns:

e.g.

Mum: „I think we need to take you to

the doctor.”

Child: „Can she doc my head?”

Examples of children’s creativity

in language use

Unfamiliar formulas

e.g.

Adult guest at a party: „I’d like to

propose a toast!”

Child: „I’d like to propose a piece of

bread!”

Examples of children’s creativity

in language use

Question formation

e.g.

„Are dogs can wiggle their tails?”

„Are those are my boots”

„Are this is hot?”

Examples of children’s creativity

in language use

Order of events

e.g.

„You took all the towels away

because

I can’t dry my hands.”

Innatists’ views on learning the

first language

●„The logical problem of language aquisition:

children come to know more about the

structure of their language than they could

reasonably be expected to learn on the basis

of the samples of language they hear”

Noam Chomski (1959),

review of B.F. Skinner (1957) Verbal behaviour

Innatists’ views on learning the

first language

The logical problem:

e.g. a)

John saw himself.

b) *Himself saw John.

c) Looking after himself bores John.

d) John said that Fred liked himself.

e) *John said that Fred liked himself.

f) John told Bill to wash himself.

g) *John told Bill to wash himself.

h) John promised Bill to wash himself.

i) John believes himself to be intelligent.

j) *John believes that himself is intelligent.

K) John showed Bill a picture of himself

howchildrenaskqus

Innatists’ views on learning the

first language

All human languages are fundamentally

innate

The input from environment (speech)

makes only a basic contribution – the

biological programming does the rest

Language develops in the same way as

other biological functions e.g. walking,

seeing

(animal instincts, critical period hypothesis, deaf

children/parents)

The same universal principles underlie all

languages (Universal Grammar)

Innatists’ views on learning the

first language

Universal Grammar – evidence:

– universality of complex language

(‘Stone Age’ tribe in New Guinea, 1930, Michael Leahy; Mt Kilimanjaro,

Bantu lg: Kivunjo, Cherokee)

- grammar in action: pidgins and

creoles

(children reinvent lg, Dereck Bickerton, 1970s sugar

plantations in Hawaii)

- mental disability, SLI

(Christopher)

- children brought up in different

environments (e.g. SAE vs. BEV)

Universal Grammar

- main assumptions

Universal Grammar – evidence:

- language universals

by Greenberg

(1966):

- lexical categories

(noun, verb)

- structure dependency

(SVO,OVS,VSO)

- phrase structure consisting of

Head, Specifier and Complement

- recurent structures

(phrases containing

a Head of the same type as the phrase)

Universal Grammar

- main assumptions

Universal Grammar – evidence

by Chomsky

:

-

People know which sentences are

grammatically well formed in their native

language

- They have this knowledge also of previously

unheard sentences

- So they must rely on mentally represented

rules and not only on memory

The final rules of a language depend on a set of

universal rules - principles (true for all languages)

and a set of parameters (features specific for the

particular language e.g. omission of a subject)

Universal Grammar

- main assumptions

Universal Grammar – evidence:

● language universals (principles)

by

Chomsky (continued)

- Projection Principle (syntactic structure is

determined by entries in the lexicon e.g. give, let)

- Subjacency Principle (any constituent of a

sentence that is moved can only cross one major

boundary e.g. questions)

- Binding Principle (anaphors e.g. himself, each

other can only refer to antecedents within the

same sentence (unlike other pronouns))

Universal Grammar

- main assumptions

● language universals (principles)

by Chomsky (continued)

- Grammar is generative: finite set of

words can generate an infinite number of

sentences

- The inborn grammar system specifies all

possible patterns which are correct and

excludes those that are not

.

.

Generative Grammar

- main assumptions

● language universals (principles)

by Chomsky (continued)

Many differences among languages represent

not separate designs but different settings of

a few "parameters" that allow languages to

vary.

The notion of a "parameter" is borrowed from

mathematics.

y = 3x + b

when graphed, correspond to a family of parallel lines with a

slope of 3; the parameter b takes on a different value for each

line, and corresponds to how high or low it is on the graph.

Similarly, languages may have parameters.

.

.

Generative Grammar

- main assumptions

● language universals (principles)

by

Chomsky (continued)

e. g. "null subject" parameter (sometimes

called "PRO-drop") is set to "off" in English

and "on" in Spanish and Italian

(Chomsky, 1981).

(In English, one can't say *”Goes to the

store”, but in French or Spanish, one can say

the equivalent.)

The reason this difference is a "parameter"

rather than an isolated fact is that it predicts

a variety of more subtle linguistic facts.

.

.

Generative Grammar

- main assumptions

● language universals (principles)

by

Chomsky (continued)

In null subject languages, one can say:

*”Ate John the apple?” or *”Do you think that left?”

This is because the rules of a grammar interact

tightly; if one thing changes, it will have

series of cascading effects throughout the

grammar.

*”

Do you think that left?”

is ungrammatical in

English because the subject of „left” is an

inaudible "trace" left behind when the

underlying subject was moved. In English trace

cannot appear after a word like „that”, so its

presence marks the sentence as ungrammatical.

.

.

Generative Grammar

- main assumptions

● language universals (principles)

by Chomsky (continued)

In French, Spanish or Polish, one can delete

subjects. Therefore, one can delete the

trace subject of „left”, just like any other

subject.

The trace is no longer there, so the

parameter that disallows a trace in that

position is no longer violated, and the

sentence sounds fine in in the ‘nul

subject’ languages.

Universal Grammar

- main assumptions

● language universals (principles)

by

Chomsky (continued)

- Language is structure dependent and provides

models of standard phrase types (deep

structure vs surface structure )

- Deep structure constituents are moved to new

slots to provide a surface structure pattern.

When it has moved it leaves a trace (t). It

enables the listener to retrieve the original deep

structure from the sentence.

e.g. Sara

is

reading

a book

.

What is Sara t reading t ?

Deep structure vs surface

structure

.

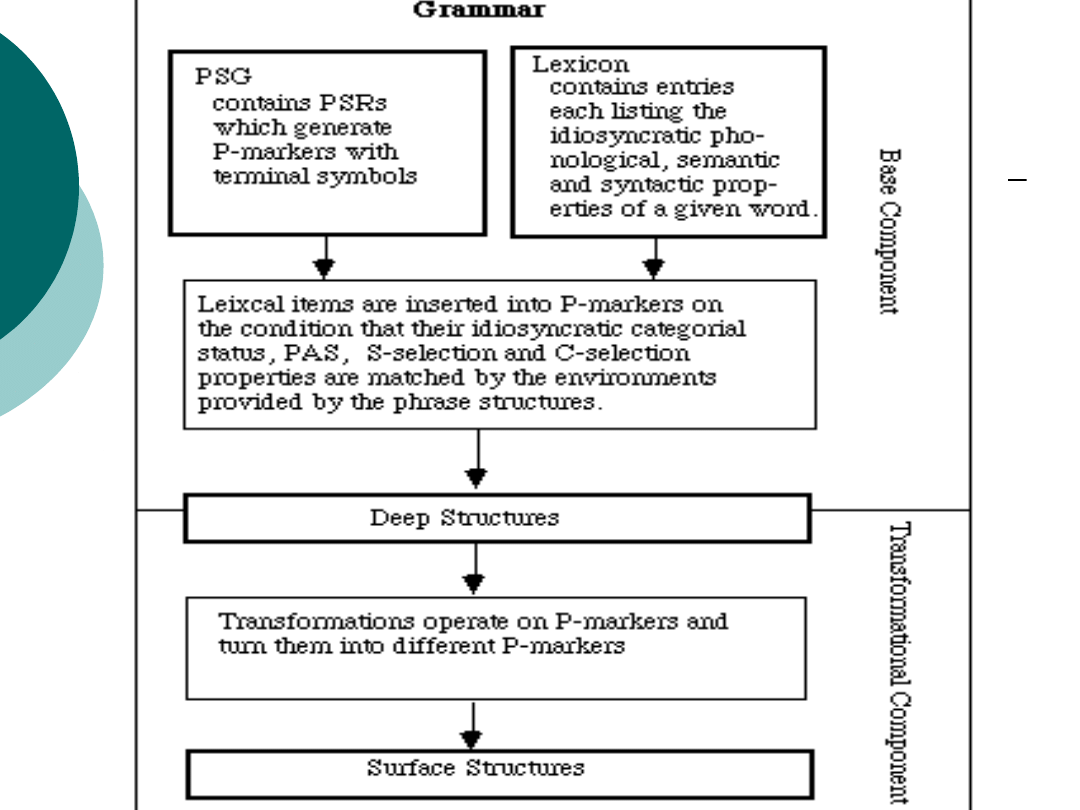

Approaches to Generative

Grammar

Aim: to come up with a set of rules or principles that will

account for the well-formed expressions of a natural

language. The term generative grammar has been

associated with at least the following schools of

linguistics:

Transformational grammar (TG)

Standard Theory (ST) (deep structure, surface structure,

1957-1965)

Extended Standard Theory (EST) (phrase structure, X-bar

theory, 1965-1973)

Revised Extended Standard Theory (REST) (restrictions

upon X-bar theory, move

α

1973-1980)

Principles and Parameters Theory (P&P) (1981-1990)

Government and Binding Theory (GB)

Minimalist Program (MP) (1990-present (a set of

questions and issues rather than a theory or a new

framework)

Approaches to Generative

Grammar

Relational Grammar (RG) (ca. 1975-1990,

subject, direct object, indirect object determine the

structure of utterances

)

Lexical-Functional Grammar (LFG,

movement

paradox: *I aren't allowed to do that

Aren't I allowed to do that?

)

Generalised Phrase Structure Grammar

(GPSG, context free)

Head-Driven Phrase Structure Grammar

(HPSG)

Categorial Grammar

Tree Adjoining Grammar

Generative Grammar

- main assumptions

Based partially on mathematical equations

generative grammar is a set of rules

which define a possibly infinite set of finite

strings

The ability to acquire such sets of rules is

most probably uniquely human.

The set, made up of fixed elements, provides

a framework for all the grammatically

possible sentences in a language, excluding

those which would be considered

ungrammatical.

Generative Grammar

- main assumptions

A classical generative grammar consists

of four elements:

A limited number of nonterminal signs

(e.g. word class labels like noun, verb, etc.) ;

A beginning sign which is contained in

the limited number of nonterminal signs

(e.g. sentence);

A limited number of terminal signs

(e.g.

vocabulary);

A finite set of rules which enable

rewriting nonterminal signs as strings of

terminal signs.

Generative Grammar

- main assumptions

If we take a generative grammar which consists of

the set of nonterminal symbols {X,Y} with X

the start symbol, the set of terminal symbols

{a,b}, and the rules X->aYb, Y->Xb, and Y-

>ba.

Applying X->aYb, followed by an application of Y ->

Xb yields the intermediate string aXbb. This string

still contains a nonterminal symbol. Therefore, it

requires reapplication of the rule X->aYb (yielding

aaYbbb) and subsequently the rule Y -> ba to

yield a string that consists solely of terminal

symbols, in this case aababbb.

Generative Grammar

- main assumptions

In English: the red book but *the book red

Descriptive grammar: adj. go in front of nouns, not after them

Generative grammar: the order specified in the rewriting rule: NP -> Det

AP N.

In this rule, a noun phrase (NP) is rewritten as a string in which

the Determiner (Det) is followed by the adjectival phrase (AP)

and the noun (N) in that order: NP -> Det AP N.

Replacing the nonterminal symbols Det, AP and N by the

terminal symbols: the, red and book resp. yields the red

book.

By contrast, the rewriting rule which makes adjectives end up

after nouns (NP -> Det N AP) is not part of the generative

grammar of English.

The generative grammar thus provides a fully explicit syntax,

rather than the informal or implicit characterization often

found in traditional grammars.

Generative Grammar

- main assumptions

Generative grammar is recursive, which

means that any output of application of

rules can be the input for subsequent

application of the same rule. That should

enable generating strings like:

the daughter of the father of the brother

of his cousin.

(NP -> NP’(D+N) + PREP + NP(D+N)’’)

Generative Grammar

- main assumptions

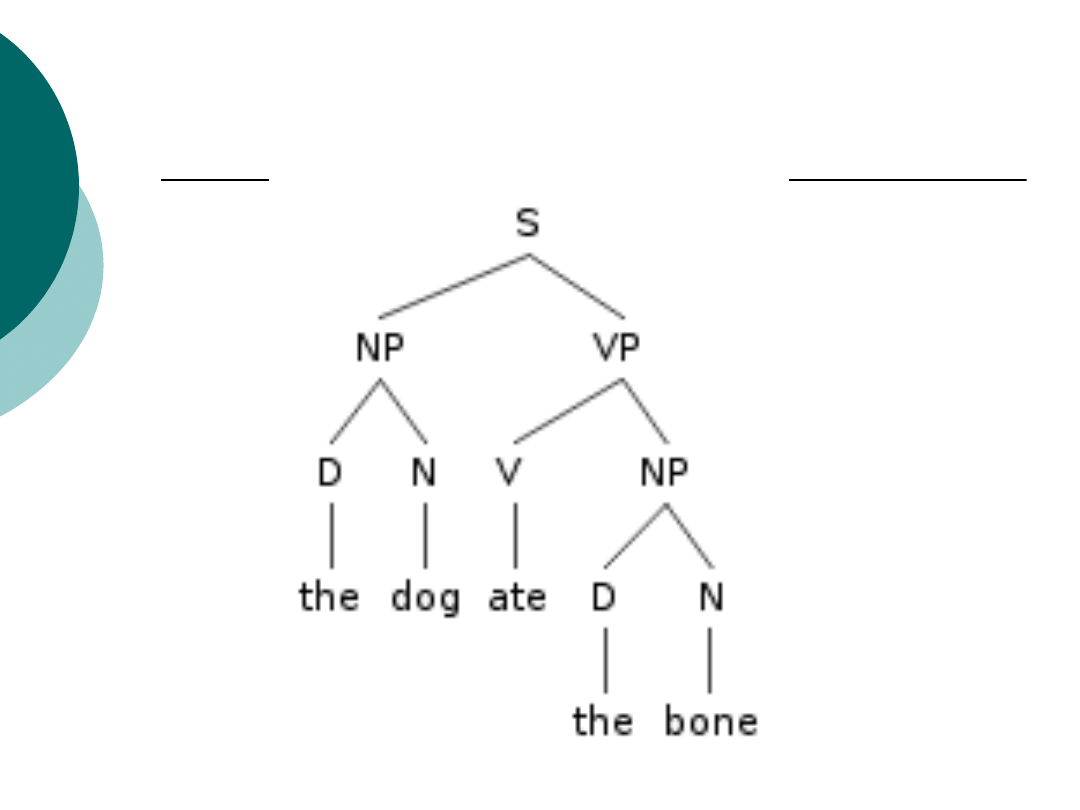

S - > (

NP(D+N)

+

VP(V+NP’(D+N

)))

e.g.

The dog

ate the bone

.

My sister

painted a picture

.

Some students

did their homework

.

The flood

destroyed many areas

.

S - > (NP(D+N) + VP(V+NP’(D+N)))

e.g.

The dog ate the bone.

Critique of innatists’ views on

learning the first language

Complex language is common

among human beings but so is Coca

Cola

Universal Grammar reflects

universal experience and limitations

of information processing

People learn to communicate

because it is useful in everyday life

Language vs thought

Language = thought?

Early behaviorists: „Thought equals sub vocal

speech”

(Smith , Brown, Toman and Goodman, 1947,

paralyzing drug

)

Language ≠ thought?

Levy: Language is independent of thought

and is served by a specialized module of

language-specific representations and

processes

(Williams syndrome, linguistic savants)

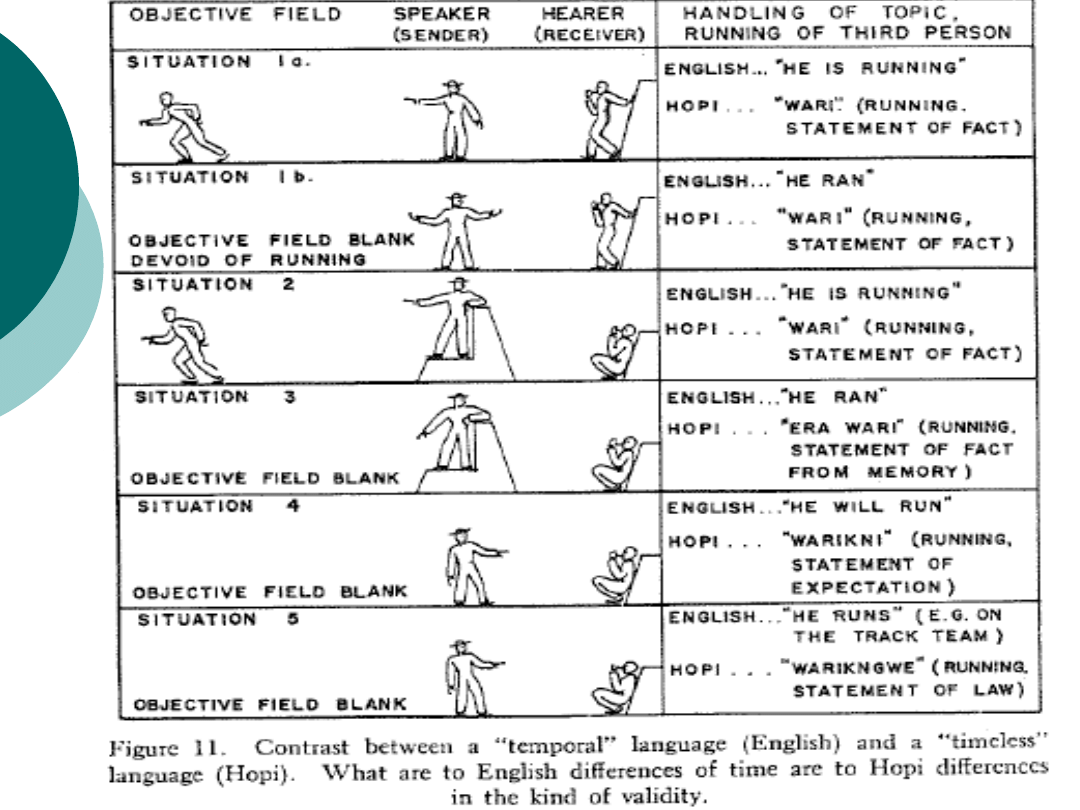

Language vs thought

- Language => thought?

Linguistic relativism: Thought is shaped

by the nature of language

Linguistic determinism: The way we

think is determined by the language we

speak (Sapire&Whorf)

(snow-Eskimo lg,

time-Hopi lg

Humboldt: “The differences between

languages are not those of sounds and

signs but of differing world views.”

(infants, animals, mental images)

Language vs thought

- Thought => language

Piaget: „The development of language is

determined by the stages at which

cognitive concepts are acquired.”

Boroditsky: “What we normally call

‘thinking’ is in fact a complex set of

collaborations between linguistic and

nonlinguistic representations and

processes”

(space/time)

Interactionists’ views on learning

the first language – latest

developements

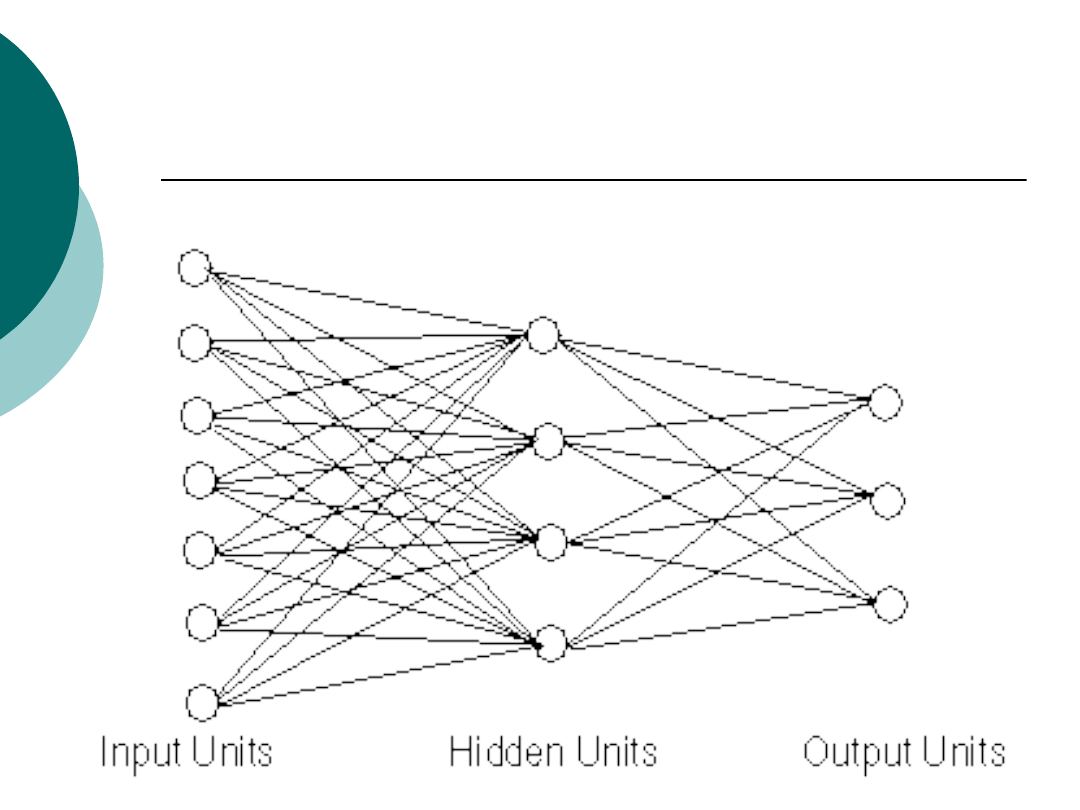

Connectionism

:

learning from

environmental stimuli and storing this

information in a form of connections between

neurons

Learning a language is basically improving the

strength of your network's connections.

If the connections between the words are stronger,

you should be a better speaker, because you can

more easily come up with antonyms, synonyms

and other related words

(‘cow’, Parallel Distributed Processing,

past tense forms, less is more,)

Interactionists’ views on learning

the first language – latest

developements

An illustration of a simple neural network

Interactionists’ views on learning

the first language – latest

developements

Computationalism:

mental activity is

: the mind operates by

performing purely formal operations on

explicit symbols

(e.g word classes or functional categories)

-

symbolic sub-systems are designed to

support learning a particular skill e.g.

language

-

mind (and language as its representation) is

made up of a structure of explicit symbols (

) and

rules for their

internal manipulation

Interactionists’ views on learning

the first language – latest

developements

An artistic representation of a Turing machine

A Turing machine is a theoretical

device that manipulates symbols

contained on a strip of tape. Described

by

in 1937 it is a

computing machine (thus they have

never actually been constructed). They

help computer scientists understand

the limits of mechanical computation.

Interactionists’ views on learning

the first language – latest

developements

How language might be computed:

(theoretical constuct using the Turing machine model)

Socrates

is a man.

Every man

is mortal.

Socrates is mortal.

Reasoning – Artificial Intelligence!

Interactionists’ views on learning

the first language – latest

developements

Emergentism: learning is

a complex

phenomenon which results from the

aggregation, organization, and interaction

of component parts within a particular

constellation, system, or context

Linguistic emergentism assumes that

language use and acquisition emerge

from basic processes that are not

specific to language

Interactionists’ views on learning

the first language - overview

Human beings are able to learn from

experience

Cognitive development and acquisition of

language are connected and dependent

on each other (children use words for

concepts they understand e.g. „bigger”)

Environment plays a major role in the

development of language

Language is one of many symbol systems

developed in childhood (e.g. body

language, abstract maths)

Document Outline

- Slide 1

- Slide 2

- Slide 3

- Slide 4

- Slide 5

- Slide 6

- Slide 7

- Slide 8

- Slide 9

- Slide 10

- Slide 11

- Slide 12

- Slide 13

- Slide 14

- Slide 15

- Slide 16

- Slide 17

- Slide 18

- Slide 19

- Slide 20

- Slide 21

- Slide 22

- Slide 23

- Slide 24

- Slide 25

- Slide 26

- Slide 27

- Slide 28

- Slide 29

- Slide 30

- Slide 31

- Slide 32

- Slide 33

- Slide 34

- Slide 35

- Slide 36

- Slide 37

- Slide 38

- Slide 39

- Slide 40

- Slide 41

- Slide 42

- Slide 43

- Slide 44

- Slide 45

- Slide 46

- Slide 47

- Slide 48

- Slide 49

- Slide 50

- Slide 51

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

3 Theories of the First language?quisition

Year II SLA #3 Theories of First Language Acquisition

Lecture XIII First language acquisition

First Language Acquisition

Lecture XIV First language acquisition

Year II SLA #2 First Language Acquisition

First Language Acquisition Vs Second Language Learning

4 Theories of the Second Language?quisition

Ellis R The study of second language acquisition str 41 72, 299 345

Han, Z H & Odlin, T Studies of Fossilization in Second Language Acquisition

A practical grammar of the Latin languag

the Placement tests for Speakout Speakout Overview of Testing Materials

An Elementary Grammar of the Icelandic Language

ebook The Secret Language of Women

THE HISTORY OF THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE 2

Analysis of the First Crusade

The?onomic Underpinnings of the First British Industrial R

Exalted Dreams of the First Age Map of Creation 2e

więcej podobnych podstron