The Marriage of Figaro Page 1

The Marriage of Figaro

“Le Nozze di Figaro”

Italian opera in four acts

by

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Libretto by Lorenzo da Ponte after

Beaumarchais’s play

La Folle Journée ou

Le Mariage de Figaro,

“The Crazy Day, or

The Marriage of Figaro” (1784)

Premiere at the Burgtheater, Vienna,

May 1786

Adapted from the

Opera Journeys Lecture Series

by

Burton D. Fisher

Story Synopsis

Page 2

Principal Characters in the Opera

Page 2

Story Narrative/Music Highlights

Page 3

Mozart..

.and The Marriage of Figaro

Page 16

the Opera Journeys Mini Guide Series

Published and Copywritten by Opera Jour-

neys

www.operajourneys.com

The Marriage of Figaro Page 2

Principal Characters in the Opera

Count Almaviva

Baritone

Countess Almaviva

Soprano

Figaro, the Count’s valet

Baritone

Susanna, lady-in-waiting

to the Countess,

betrothed to Figaro

Soprano

Cherubino, a young page Soprano

Dr. Bartolo, a physician Bass

Marcellina, Dr. Bartolo’s

housekeeper

Contralto

Don Basilio, music master

Bass

Antonio, a gardener,

and Susanna’s uncle

Bass

Don Curzio, a lawyer

Tenor

Barbarina, Antonio’s daughter

Soprano

TIME and PLACE: The 18

th

century.

The Count Almaviva’s chateau in the

country-side near Seville

Story Synopsis

In the first episode of the trilogy, The Barber of

Seville story, Count Almaviva courts Rosina, luring her

from the jealous guardianship of Dr. Bartolo through a

series of subterfuges, intrigues, and adventures, all

engineered by Figaro, Seville’s illustrious barber, factotum,

and jack-of-all-trades.

In the second episode, The Marriage of Figaro,

Count Almaviva has married Rosina: she is now the

Countess Almaviva; Figaro is the Count’s valet, the

additional reward he received for his services during the

course of the plot of The Barber of Seville; and Dr.

Bartolo has become the “doctor of the house.” Dr. Bartolo

seethes with revenge against Figaro for having outwitted

him and enabling the Count to marry Rosina. Together

with the housekeeper, Marcellina, who also harbors

resentment toward Figaro, both conspire for vengeance

against Figaro.

The noble Count Almaviva of the The Barber of

Seville story, has become transformed into a philanderer

with amorous designs on Figaro’s bride-to-be, Susanna,

the Countess’s personal maid.

The Marriage of Figaro story deals with 18

th

century

social struggles between lower class servants and their

aristocratic masters, the intrigues in their relationships

complicated by sex, rivalries, jealousies, and revenge.

The Marriage of Figaro Page 3

Story Narrative with Music Highlights

Overture:

The Overture to The Marriage of Figaro captures

the spirit of the opera: its themes are specific to the

Overture and do not appear elsewhere in the opera.

Mozart musically suggests the story’s underlying

ironies and satire: the Overture contains bubbling and

delightful music that conveys rollicking good humor, as

well as subtle suggestions of the story’s intrigues and

skullduggery.

ACT I: Scene 1 - A room assigned to Figaro and

Susanna.

Figaro and his bride-to-be, Susanna, are making last

minute preparations for their wedding. The Count has

assigned them to new quarters, and presented them with

the present of a new bed. Figaro is preoccupied with

measuring if the bed will fit or not, while Susanna tries

on a hat and veil she has made herself, and plans to wear

at her wedding: the traditional wreath of orange blossoms,

known as le chapeau de mariage. Susanna tries in vain

to get Figaro to take interest in her hat, and then becomes

petulant. Finally, he heeds to her demands, gives her

attention, and acknowledges her hat.

Intuitively, Susanna has become suspicious of the

Count’s sudden “generosity” in providing them with a

room so close to his own quarters. At the same time, she

becomes exasperated by Figaro’s unsuspecting

complacency, and his failure to realize that the proximity

of their rooms may indeed be an intentional ploy on the

part of the lustful Count. Susanna awakens Figaro: she

suspects that the Count does not really want her close to

her mistress, the Countess, but rather, conveniently

located so that he could invent an errand to dispense

with Figaro, and then she would be at his mercy.

Their master has become a philanderer: rather than

seek licentious amusement away from home, he has

decided that he has many opportunities for amorous

adventure right in his own chateau. Susanna has heard

from Don Basilio that the Count has intentions of renewing

the droit de seigneur, or ius primae noctis, the old custom

of “the feudal right of the lord,” the tradition by which

the lord of the manor, in compensation for the loss of

one of his female servants through marriage, had the

right to deflower his feudal dependents before the husband

took possession. Nevertheless, Susanna has become his

intended victim, and with his customary despicable

arrogance, he intends to achieve with consent from

Susanna, the right he ceded by law.

Upon hearing Susanna’s revelation, Figaro becomes

The Marriage of Figaro Page 4

stunned, unable to comprehend the Count’s betrayal of

him after he provided his unstinting help and friendship

during the Count’s courting of Rosina. Figaro becomes

alarmed, and is now convinced that the Count, if he

succeeds in becoming the ambassador in London, will

send him off as his courier, and then have Susanna at his

mercy.

Figaro decides that he must outwit his master, and

with his customary confidence, concludes that the Count

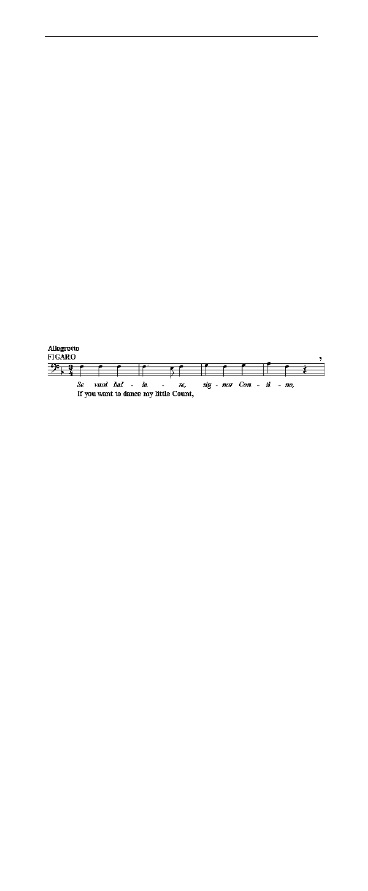

will never be able to match his ingenuity. In his aria, Se

vuol ballare, Signor Contino, “If you want to dance my

little Count,” Figaro sums up the underlying conflict and

tension within the entire opera story: the lower classes

need for cunning to survive under aristocratic power.

Although Susanna is confident she can control the

lascivious Count, Figaro is more apprehensive, and even

somewhat jealous.

Figaro: Se vuol ballare, signor Contino….

In a moment of need, Figaro had borrowed money

from Marcellina, Dr. Bartolo’s housekeeper, however,

lacking collateral, he promised to marry her if he did not

reimburse her. Marcellina arrives to demand repayment

from Figaro, and with the encouragement and assistance

of Dr. Bartolo, intends to legally force Figaro to repay

her. Likewise, Dr. Bartolo still antagonistic and bearing

a grudge against Figaro, seeks revenge against him for

his trickery in helping the Count lure Rosina from him.

Further gratifying Bartolo is the opportunity to rid himself

of the now extremely unattractive Marcellina, who, many

years earlier, bore Dr. Bartolo an illegitimate son.

Marcellina and Dr. Bartolo unite and become

impassioned accomplices in their conspiracy against

Figaro: Dr. Bartolo concludes that his hour of revenge

against “that rascal Figaro” may have come at last, and

expresses his excitement in the traditional grand buffo

style, his patter aria: La vendetta, oh, la vendetta!

“Vengeance, oh vengeance!”

When Susanna reappears, Marcellina provokes her

into a rivalry for Figaro by planting seeds of jealousy.

The two women argue with mock courtesies, sarcasm,

and feigned sincerity and politeness: Marcellina refers to

Susanna with spite and disdain, calling her “the Count’s

beautiful Susanna.” Likewise, Susanna uses her wedding

dress as a metaphor for aging, comparing it to the old

Marcellina, who duly explodes after recognizing the insult

to her advancing age.

The Marriage of Figaro Page 5

Cherubino, the Countess’s page, arrives, an

adolescent whose pulse uncontrollably races from his

youthful passion for all womankind: his hyperactive

hormones seem to place the ubiquitous page in all of the

wrong places at the wrong time. Cherubino suffers from

youthful erotic awakenings: he falls in love with any

woman in sight, and it seems, always the wrong woman.

Yesterday, in particular, Cherubino aroused the

Count’s anger: the Count caught him in a rendezvous

with Barbarina, the gardener Antonio’s daughter. After

the Count’s angry warning, he fears his fury: the

consequence, that he would be sent away. Cherubino

begs Susanna to intercede with her mistress, the

Countess, so that the Count may be dissuaded from his

agitation.

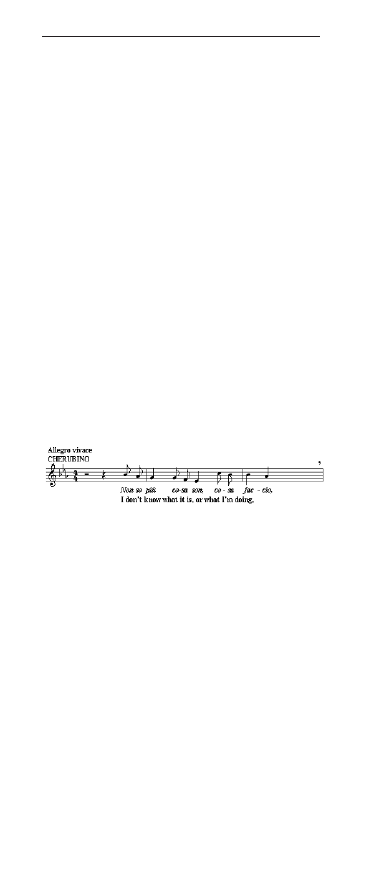

However, true to his uncontrollable passions, the

young Cherubino reveals to Susanna that he has fallen

deeply in love with no less a personage than the Countess

herself. He seizes a ribbon from Susanna which belongs

to the Countess. He becomes ecstatic and inspired, and

delivers a canzonetta he has just written for the Countess

which expresses his erotic ecstasies and passions,

sensibilities which he cannot understand and confuse

him.

Cherubino: Non so piu cosa son, cosa faccio…

Suddenly, the new quarters of Susanna and Figaro

are invaded by the Count himself. Cherubino, fearing the

Count, particularly because he should not be in Susanna’s

quarters at all, hastily conceals himself behind a chair.

The Count, believing his is alone with Susanna, explains

that he may receive an ambassadorship to London, and

suggests to Susanna that his appointment would provide

a magnificent opportunity for them to develop a

relationship: of course, the unsuspecting Count’s amorous

advances are overheard by Cherubino.

Footsteps are heard approaching: Cherubino emerges

from behind the chair and sits in the chair; Susanna covers

him with her bridal dress. The Count likewise hides to

avoid being seen in a potentially scandalous situation: he

hides himself behind the same chair Cherubino has just

left.

The new guest is Don Basilio, the chateau’s gossiping

music master and ingenious fabricator of intrigues. He

proceeds to make malicious – yet accurate - insinuations

about Cherubino’s rapturous flirtations and amorous

behavior toward the Countess. The Count, from hiding,

overhears Basilio’s blasphemous accusations about his

wife, and emerges from behind the chair: he erupts into

The Marriage of Figaro Page 6

a towering rage, and demands details and an explanation

from Basilio.

In fear, Basilio retracts his accusations, excusing

them as mere “suspicion.” Nevertheless, the Count’s

jealousy has been aroused against the young page who

has become a thorn to his amorous pursuits: he insists

that he will take action and expel Cherubino from the

chateau. He describes how yesterday, he discovered

Cherubino hiding under a table in Barbarina’s room,

obviously chagrined that Cherubino’s presence thwarted

his amorous advances toward Barbarina.

When the Count drew away the table cloth he

discovered Cherubino hiding under the table. As he

demonstrates the event, he sweeps aside Susanna’s dress

from the chair, and in shock, surprise, and exasperation,

for the second time in a mere few days, he finds

Cherubino again in a compromising situation. The Count

becomes indignant; Susanna expresses horror; and Don

Basilio erupts into malicious delight and laughter.

But now the Count concludes that Cherubino and

Susanna are having a clandestine affair. The Count

becomes furious. Not only has Cherubino overheard his

failed attempts to seduce Susanna, but in his mind, the

lad seems to have had more success with Susanna than

he himself. The Count realizes that he now has an

opportunity to avenge his cunning valet, so he sends

Basilio to fetch Figaro so he can reveal his betrothed’s

“infidelities.”

Figaro arrives with a group of peasants, all ironically

singing praises to their magnanimous master: the man of

virtue who abolished the ancient aristocratic privilege of

droit de signeur. Figaro, not realizing the situation’s irony,

requests that at their wedding, the Count should place

the wedding veil on Susanna’s head to symbolize the

bride’s innocence

The Count again becomes thoroughly obsessed with

his problem with the omnipresent Cherubino. Susanna

suggests that he forgive the innocent and naïve lad, but

the Count has a sudden inspiration: he has contrived a

plan to rid himself completely of Cherubino. He accedes

to Susanna’s request and agrees to pardon Cherubino,

but in return, the boy will receive an officer’s

commission in his Seville regiment. Now delirious with

his impending resolution to his problem with Cherubino,

the elated Count and the malicious Don Basilio depart.

Cherubino shakes in dreaded fear as Figaro taunts

him, painting a vivid picture of the glories and terrors of

military life: now, instead of flirtation and tender love-

making, Cherubino will embark on a military career and

be subject to weary drills and marching.

The Marriage of Figaro Page 7

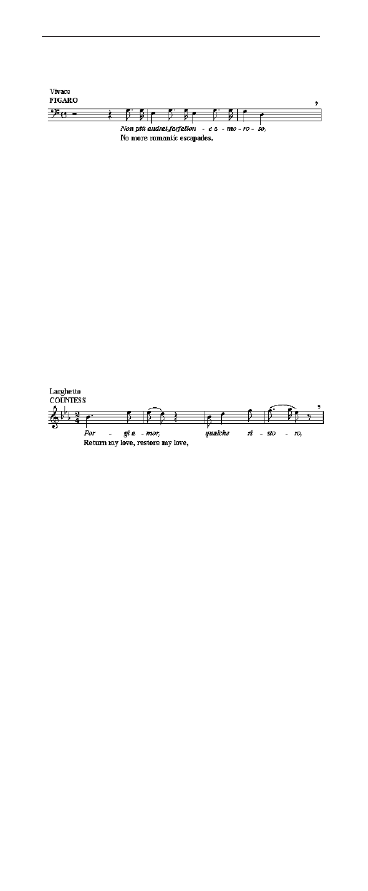

Figaro: Non più andrai farfallone amoroso….

Figaro exults in the idea of Cherubino’s departure:

like the Count, his life will certainly be sweeter without

the menacing presence of this impetuous lad.

ACT II: The Countess’s apartment

The Countess, alone with her thoughts, meditates

about her happy past, and her unhappy present. She

deeply loves her husband, but she has slowly realized

that she is not the only woman in his life. The Countess,

touchingly and expressively, vents her distressed feelings,

praying for relief from her grief, and ultimately, that her

husband’s affections may be restored to her.

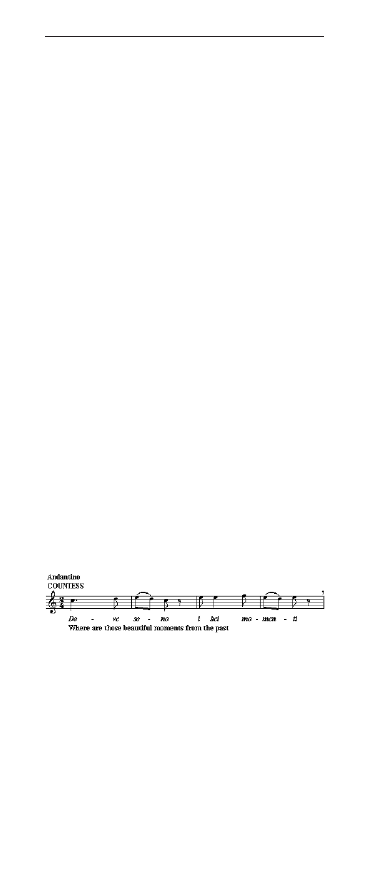

Countess: Porgi amor, qualche ristoro….

The Countess, despairing about the Count’s wayward

affections, joins with Susanna and Figaro to invent a

scheme that will serve to thwart the Count’s amorous

adventures. They decide to launch a plot to outwit him:

they will expose his infidelities, ridicule and embarrass

him, and teach him a lesson. If they can make him jealous,

he will then be persuaded to change his ways, return to

being a faithful husband, and his love for the Countess

will be reawakened.

Their intrigue involves having the Count discover an

anonymous letter which reveals that the Countess has

made a rendezvous with a secret “lover.” The resourceful

Figaro will arrange to have Don Basilio deliver the “false”

note to the Count. At the same time, Susanna will arrange

a clandestine rendezvous with the Count, but Cherubino

will be in her place, dressed in her clothes: after Figaro’s

description of military life, Cherubino will do anything to

postpone his entry into the army.

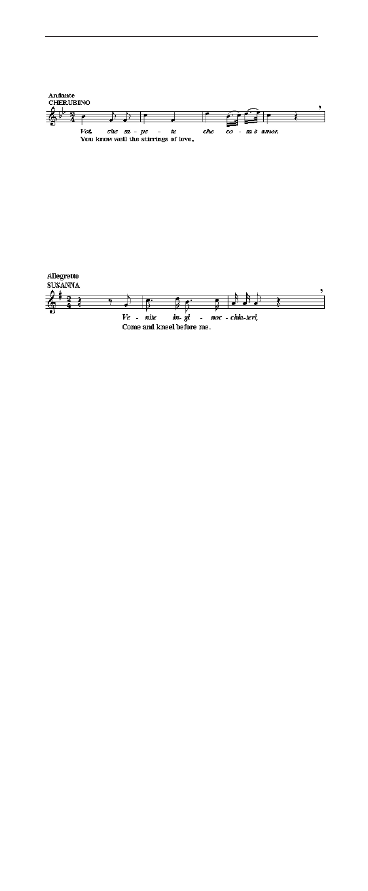

Cherubino arrives, and is delighted and excited by

the thought of seeing the Countess before his departure.

Susanna persuades him to entertain the Countess and

sing the song he has written for her, but this time, the

promising young composer and song-writer, sings a

“romance” which complements the Countess on her

insight into the intrigues of love and romance.

The Marriage of Figaro Page 8

Cherubino: Voi che sapete che cosa è amor….

The Countess sees Cherubino’s commission and

remarks that it lacks the official seal. As Susanna proceed

to dress Cherubino in woman’s clothes for the

masquerade, she becomes frustrated by the impetuous

youth who keeps turning to look at the Countess..

Susanna: Venite inginocchiatevi…

Just as Cherubino’s disguise is completed, the Count

is heard angrily knocking at the door. Cherubino, fearing

another encounter with his master, immediately hides in

an adjoining closet. The Count is in a rage: Basilio

delivered the Countess’s “false” invitation for a

rendezvous with a secret lover, and suspecting his wife’s

infidelity, he has returned precipitately from the hunt. He

finds the Countess’s door locked – an unprecedented

action – and his suspicions become further aroused.

The door is opened, and immediately, the Count

presents his wife with the “note” and proceeds to

immediately incriminate her infidelity. Noises heard from

an adjoining room – Cherubino, of course – which further

arouse the Count’s suspicions. Nervously, the Countess

tries to stall and deter the Count, excusing the noises as

those from her maid Susanna who is in the room

dressing. But the Count, overcome with jealousy, as well

as the fear of scandal and the ridicule of a cuckolded

husband, suspects a hiding lover, and proceeds to demand

that Susanna – if it is indeed Susana, come out of the

room.

The Count desperately and unsuccessfully tries to

physically open the door. Thwarted in his attempts, he

leaves to secure tools to break down the door, but he

insists on taking the Countess with him. Both the Count

and Countess depart, in effect, locking both Susanna

and Cherubino inside. After they depart, Susanna fetches

Cherubino, and with no other exit, the frightened and

intimidated Cherubino escapes by jumping out of an open

window, his jump witnessed by the Antonio, the gardener,

who becomes puzzled and disconcerted in his state of

drunkenness.

Now alone, Susanna proceeds to hide herself in the

adjoining closet and await the return of the Count and

The Marriage of Figaro Page 9

Countess. The Count returns and tries to forcibly open

the door, but the Countess, unaware that Cherubino has

escaped and that Susanna has replaced him, becomes

anxious and nervous. She decides that she has no

alternative but to confess to her husband that it is indeed

the young Cherubino in the closet, and at the same time,

tries to persuade the Count that Cherubino is merely an

innocent young lad not worthy of his anger.

Nevertheless, the Count has become even angrier

and inflamed with rage: he has become blind with jealousy,

particularly after he discovered the “note” in which the

Countess planned a secret rendezvous with a lover. He

disregards the Countess’s anxious pleading to placate

him, and is convinced that her secret lover hides in the

closet.

The Count breaks down the door, and with drawn

sword, orders the Countess’s lover out from the closet.

When the door opens, a surprise awaits the Count and

Countess: Susanna steps calmly out of the closet. The

Count stands in shock and surprised: the Countess is

amazed and expresses relief in resolving a seemingly

insoluble dilemma; and Susanna stands in front of the

door, the picture of wide-eyed innocence. In effect,

Susanna’s emergence from the closet has confirmed the

Countess’s original story: it was indeed Susanna dressing

in the closet. The Countess excuses her “confession,”

and claims that it was only a ruse to inflame the Count:

she knew all the time that it was Susanna in the room.

But the Count, humiliated by being made into a fool,

refuses to believe that Susanna was alone in the dressing

room. While the Count momentarily leaves the room,

Susanna tells the Countess not to worry, since Cherubino

has escaped through the window.

The Count returns, confused and embarrassed, his

suspicions now unfounded. He becomes penitent, asks

forgiveness for his behavior, and confirms his love for

the Countess. When he addresses the Countess as Rosina,

emotions flare as the Countess becomes angry and bitter,

reminding him of his neglect and indifference: Crudele,

più quella non sono!, “No, Not Rosina any more…”

Nevertheless, the Count is still puzzled: he wants an

explanation about Bartolo’s anonymous “note,” and still

suspects that somehow it was indeed Cherubino hiding

in her dressing room. The Countess explains that it was

all part of a harmless joke perpetrated by Figaro to

provoke and tease him. The Count begs her forgiveness

again, and this time, she grants it.

Excitedly, Figaro arrives and announces, albeit for

the second time, that the musicians have assembled, and

now all the arrangements are in place and their wedding

can proceed. However, Figaro has arrived at an

The Marriage of Figaro Page 10

inopportune moment, and the wary and suspicious Count

seizes his chance to ask Figaro about the infamous “note,”

asking him if he knows anything about it. Figaro, the

ultimate prevaricator, vigorously denies any knowledge

of it, but with whispers from Susanna and the Countess,

his memory becomes sharpened, and he admits that he

was the writer.

The situation becomes even more confounded as

the gardener Antonio arrives, inebriated, but also angry,

and complaining that someone jumped out of the window

of the Countess’s room and trampled on his flowers and

broke a flower pot. Figaro quickly admits that he was

the culprit and even shows them that he injured his leg in

the process.

After Figaro’s admission, Antonio confronts them

with a paper that he must have dropped: Cherubino’s

officer’s commission. The Count senses chicanery and

grabs the paper, and testing Figaro, asks him what its

contents are. The Countess recognizes it, reveals to

Susanna that it is the Cherubino’s commission, Susanna

in turn whispers it to Figaro, and then Figaro, now

prompted by the women, reveals its contents.

The Count asks why the commission was in Figaro’s

possession, and again, the Countess prompts the answer

through Susanna’s subtle whispers. With great

confidence, Figaro vindicates himself and announces that

Cherubino gave him the commission to secure its missing

seal.

Figaro now faces a serious crisis. Dr. Bartolo,

Marcellina, and the malicious Don Basilio burst in

demanding justice: Figaro must make good on his promise

to repay Marcellina’s loan to him; if he cannot, as he had

promised, he is legally bound to marry her. The Count

becomes ecstatic: he now has found a means to avenge

his wily valet; after all, if Figaro is out of the way, he can

prevent Susanna from marrying Figaro, and then, he

would have no obstacle in pursuing her.

The Count consents to hear the case and will act as

magistrate to adjudicate Marcellina’s claim: his decision

is already biased, and he is eager to settle accounts with

his valet.

All these complications between servants and masters

must await resolution: the Count again postpones the

marriage between Figaro and Susanna.

ACT III: A large hall in Count Almaviva’s chateau

Count Almaviva eagerly seals Cherubino’s army

commission, thus ridding himself of this youthful rival

for his wife’s affections, as well as those of the women

in his chateau. He then reflects on the senselessness of

all those recent strange events and remains puzzled and

suspicious. He refuses to accept or believe Figaro’s

The Marriage of Figaro Page 11

explanations, so he still wonders: Who jumped from

the balcony? Who is the Countess’s lover? Who wrote

the anonymous “note”?

Susanna approaches the Count. The Count anxiously

complains that Susanna torments him, and in his lust, he

pleads for her love and suggests a rendezvous. Susanna

tries to dissuade him, and then to put their charade scheme

into motion, she agrees to meet him for a tryst in the

garden that evening after her wedding. The impatient

Count becomes elated in his triumph: finally, he will

have his moment to seduce Susanna, and at the same

time, his revenge against Figaro.

But in truth, Susanna’s agreement for a secret

rendezvous will enable the Countess to teach her husband

a lesson by embarrassing him: the Count will be meeting

the Countess herself dressed in Susanna’s clothes.

As Susanna departs, she runs into Figaro who is on

his way to hear Marcellina’s suit against him. Susanna

tells Figaro that his case has been won, and she has the

money to pay Marcellina. (Neither Figaro nor the Count

know that Susanna borrowed money from the Countess

to pay back Marcellina.)

But the Count overhears Figaro and Susanna. He

becomes vindictive and explodes in rage and revenge

and condemns his valet: Vedrò, mentr’io sospiro, “And

so my servant enjoys pleasure that I am denied.” In the

end, the frustrated Count concludes that Figaro, his

servant, was born to torment him and laugh at his

misfortune.

The Count presides over his court and determines

Figaro’s obligations: the stuttering lawyer, Don Curzio,

tells Figaro that he must either pay back the money to

Marcellina, or he must fulfill his obligations and marry

her. Figaro, now in a momentous crisis, creates one of

his most brilliant subterfuges: he claims that he is of

noble birth, and, therefore, he cannot marry without the

consent of his parents; he knows not who or where they

are, but he hopes to find them some day. To prove his

assertion, he shows everyone a branded spatula mark on

his arm which should help to identify him. Marcellina

recognizes the mark, and to everybody’s amazement, it

is discovered that Figaro, who grew up in ignorance of

his parentage, is Marcellina’s long-lost son: the fruit of

an early love affair between Marcellina and Dr. Bartolo.

Raging impotently, the Count watches as Figaro and his

new-found parents reunite and embrace.

Susanna now arrives with money to settle Figaro’s

debts, but unaware of the cause for celebration that she

is witnessing, she witnesses Marcellina bestowing

“motherly” kisses on Figaro: Susanna misunderstands

completely, and in a jealous rage, proceeds to box Figaro

on his ear before he gets a chance to explain his

unexpected change of fortune.

The Marriage of Figaro Page 12

Nevertheless, this moment of newfound family bonds

is full of spirit. Dr. Bartolo agrees that he will marry

Marcellina forthwith, and Figaro is heaped with gifts:

Marcellina gives her long-lost son his promissory note

as his wedding present, and Dr. Bartolo, ironically his

“father,” hands him purses of money. Susanna embraces

her future parents-in-law, and all signs point to the four

of them celebrating a double wedding: finally, there is

seems to be no obstacles to stop Susanna and Figaro

from being married.

In a short scene between Cherubino and Barbarina,

it becomes obvious that the young lad remains on the

estate and has not gone as ordered to Seville: he decides

that he will dress up as a peasant girl so he can remain

for the wedding festivities.

The Countess is deeply concerned as to how her

husband will react to the deception of their intrigue. She

deeply loves the Count, and indeed wants to punish him.

Nevertheless, she deplores the fact that she must seek

the help from her servants to win back her husband’s

affection: a plot in which she has to exchange clothes

with her maid Susanna. (The original scheme to disguise

Cherubino as Susanna has been dropped.) Sadly, she

recalls the days of her former happiness, and clings to

her hopes of renewing the Count’s devotion to her.

In a moment of tenderness and beauty, the broken-

hearted Countess laments those lost days of happiness

and bliss. Yet, she has not become embittered, and bears

no malice toward the Count, although he has obviously

been deceptive from her wedding day. Nevertheless, she

expresses hope, and yearns to restore those pleasures

from the past.

Countess: Dove sono i bei momenti…..

The Countess dictates a letter which is scribed by

Susanna in the form of a canzonetta. The devious note is

directed to the Count, and fixes the exact time and place

for the evening rendezvous: the Count is to meet Susanna

in the garden: “under the pines where the gentle zephyrs

blow.” Of course, he will not be meeting Susanna, but

rather, the Countess dressed in Susanna’s clothes. The

note is sealed with a brooch pin, and bears a request that

the Count return the brooch pin as confirmation of his

understanding and agreement to keep the appointment.

Just before the wedding ceremony, village peasant

girls arrive with flowers for the Countess, Figaro,

The Marriage of Figaro Page 13

Cherubino dressed as a peasant girl, Barbarina, Dr.

Bartolo, and the Count. The gardener Antonio, holding

Cherubino’s hat, notices that one of the “girls” in the

group is none other than Cherubino in disguise, and

proceeds to place the hat on his head. Barbarina, deeply

in love with Cherubino, comes to his rescue: in a

somewhat embarrassing declaration, she reminds the

Count of the many times he hugged and kissed her, and

then promised that he would grant her any wish; she

tells the Count that her wish now is to have Cherubino

as her husband. The Count, again facing a crisis, reacts

to this unexpected development, wondering whether

demons have overcome his destiny.

When Figaro arrives, the irritated and obsessed Count

asks him again who it was who jumped out of the window

the other morning. But the tension of the moment is

inadvertently broken as musicians start playing the

wedding march: finally, the moment for the wedding of

Figaro and Susanna has arrived.

The Count presides over the double wedding

ceremony of Susanna and Figaro and Marcellina and Dr.

Bartolo. The Count, while muttering words of revenge

against Figaro, places the wedding veil on Susanna, and

she slips him a note: the invitation to meet her in the

garden that evening. Figaro, knowing nothing about the

Countess’s new scheme, sees the Count open the note,

and in the process, pricking his finger on the brooch pin.

Figaro rightly suspects that a clandestine love intrigue is

afoot, but he does not imagine that his beloved Susanna

is involved. The Count, in anticipation of his rendezvous,

hurriedly ends the ceremony, and promises further

celebrations that evening.

ACT IV: The garden of the chateau

The Count returns the note and its confirming brooch

pin to the “messenger”: Barbarina. To her consternation

and distress, Barbarina drops the pin and loses it. Figaro

arrives and helps the unsuspecting Barbarina look for

the pin, and she disingenuously reveals the contents of

the note, and the planned rendezvous of the Count and

Susanna.

Figaro, not a confidant in this new phase of Countess-

Susanna charade, jumps to the conclusion that his new

bride, Susanna, is faithless and intends to yield to the

Count that evening. Inflamed with passions of jealousy

and betrayal, Figaro invites his new parents, Dr. Bartolo

and Marcellina, to join him and witness his new wife’s

betrayal and faithlessness.

Nevertheless, Marcellina tries to defend the constancy

and fortitude of her sex, and refuses to believe that

Susanna would deceive Figaro. But in his anger and

The Marriage of Figaro Page 14

despair, Figaro believes he is the victim of deception,

and warns all men to open their eyes to the fickleness

of women: Figaro believes he has become a cuckold.

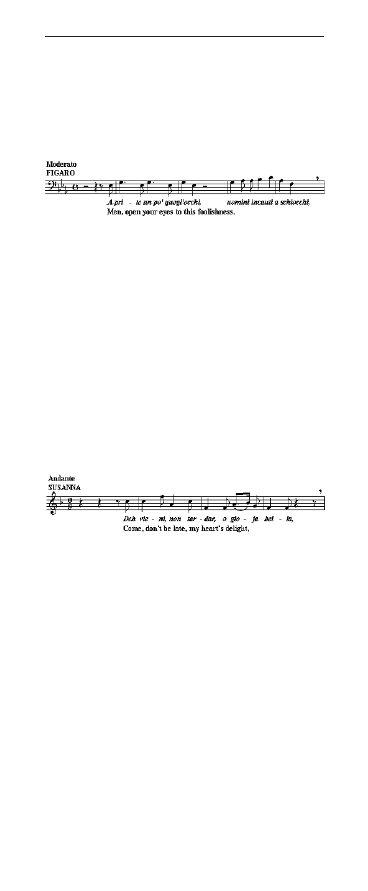

Figaro: Aprite un po’ quegl’occhi, uomini incauti a

schiocchi..

As Susanna and the Countess arrive, each wearing

the other ’s clothes. Figaro hides himself in the

expectation of catching Susanna and the Count in

flagrante.

Susanna, advised by Marcellina, knows that Figaro

is nearby and can hear everything and decides that she

has a wonderful opportunity to teach her new husband a

lesson for his mistrust. Poignantly, she addresses a song

to the supposed lover whom she awaits, telling him how

she anticipates this night of love. Figaro, aroused to

passion, overhears Susanna but cannot see her in the

dark: he does not know that it is he, not the Count, who

is the subject of her amorous reflections.

Susanna: Deh viene, non tardar, o gioja bella….

Complications and mistaken identities now abound:

it is all confusion, mistaken identities, and all blunder

into each other in the dark. Cherubino arrives, starts to

make love to the Countess, thinking, from the clothes

she wears, that she is Susanna. Suddenly, the Count

arrives, steps between them, and in the dark and

confusion, mistakenly receives a kiss from Cherubino.

Now enraged, the Count aims a blow to Cherubino’s

ears, but instead, catches the hovering Figaro. All

disappear and leave the Count alone with “Susanna,” and

he proceeds to plead for her love and embraces, little

knowing that the woman he is attempting to seduce is

his own wife, the Countess.

Figaro wanders about, and finds the real Susanna,

and assuming from her disguise that she is the Countess,

suggests that they go together and catch the Count with

Susanna. When Susanna forgets herself for a moment

and fails to disguise her voice, she gives herself away.

Intuitively, Figaro now grasps the situation perfectly, and

his jealousy instantly evaporates.

The Marriage of Figaro Page 15

In revenge, he decides to annoy Susanna and

proceeds to make theatrical declarations of passionate

love to the “Countess,” which, in turn, infuriates Susanna

and rouses her jealousy: Susanna now proceeds to rain

blows on Figaro. Their argument ends with the

newlywed’s first loving reconciliation: they play out an

impassioned amour, but Susanna is still dressed as the

Countess, and the Count looks on irate and chagrined.

But the Count, true to character, has more important

priorities: he leaves the scene en route for his rendezvous

with Susanna.

The Countess, now dressed in her own clothes,

makes a dignified appearance and clears up the entire

chaos and confusion: she advises everyone to stop playing

foolish games. Figaro, Susanna, and finally the Countess,

end the charade and open the Count’s eyes. He has been

caught in flagrante with his own wife, and realizing that

he has been outwitted, there is nothing he can do but

acknowledge his folly with as good grace as he can. In a

complete change of mood and heart, the Count begs the

Countess’s forgiveness which she lovingly grants.

All the crises seem to have been resolved and

reconciled: there is cause for celebration to begin in

earnest as all the lovers are reunited.

Beaumarchais’s “Crazy Day” ends, saved for

posterity with Mozart’s unerring musical

characterizations.

The Marriage of Figaro Page 16

The Marriage of Figaro Page 17

Mozart……………..…………..The Marriage of Figaro

W

olfgang Amadeus Mozart – 1756 to 1791 - was

born in Salzburg, Austria. His life-span was brief,

but his musical achievements were phenomenal and

monumental, establishing him as one of the most

important and inspired composers in Western history:

music seemed to gush forth from his soul like fresh water

from a spring. With his early death at the age of thirty-

five, one can only dream of the musical treasures that

might have materialized from his music pen.

Along with such masters as Johann Sebastian Bach

and Ludwig van Beethoven, Mozart is one of those three

“immortals” of classical music. Superlatives about Mozart

are inexhaustible: Tchaikovsky called him “the music

Christ”; Haydn, a contemporary who revered and idolized

him, claimed he was the best composer he ever knew;

Schubert wept over “the impressions of a brighter and

better life he had imprinted on our souls”; Schumann

wrote that there were some things in the world about

which nothing could be said: much of Shakespeare, pages

of Beethoven, and Mozart’s last symphony, the forty-

first.

Richard Wagner, who exalted the power of the

orchestra in his music dramas, assessed Mozart’s

symphonies: “He seemed to breathe into his instruments

the passionate tones of the human voice ... and thus

raised the capacity of orchestral music for expressing

the emotions to a height where it could represent the

whole unsatisfied yearning of the heart.”

Although Mozart’s career was short, his musical

output was tremendous by any standard: more than 600

works that include forty-one symphonies, twenty-seven

piano concertos, more than thirty string quartets, many

acclaimed quintets, world-famous violin and flute

concertos, momentous piano and violin sonatas, and, of

course, a substantial legacy of sensational operas.

Mozart’s father, Leopold, an eminent musician and

composer in his own right, became, more importantly,

the teacher and inspiration to his exceptionally talented

and incredibly gifted prodigy child. The young Mozart

quickly demonstrated a thorough command of the

technical resources of musical composition: at age three

he was able to play tunes he heard on the harpsichord;

at age four he began composing his own music; at age

six he gave his first public concert; by age twelve he had

written ten symphonies, a cantata, and an opera; and at

age thirteen he toured Italy, where in Rome, he

astonished the music world by writing out the full score

of a complex religious composition after one hearing.

Mozart’s musical style, and the late 18

th

century

Classical era, are virtually synonymous: their goal was

The Marriage of Figaro Page 18

to conform to specific standards and forms, to be

succinct, clear, and well balanced, but at the same time,

develop musical ideas to a point of emotionally satisfying

fullness. As that quintessential Classicist, Mozart’s music

has become universally extolled, an outpouring of

memorable graceful melody combined with formal,

contrapuntal ingenuity.

D

uring the late eighteenth-century, a musician’s

livelihood depended solidly on patronage from

royalty and the aristocracy. Mozart and his sister,

Nannerl, a skilled harpsichord player, frequently toured

Europe together, and performed at the courts of Austria,

England, France, and Holland. But in his native Salzburg,

Austria, he felt artistically oppressed by the Archbishop

and eventually moved to Vienna where first-rate

appointments and financial security emanated from the

adoring support of both the Empress Maria Thèrése, and

later her son, the Emperor Joseph II.

Opera legend tells the story of a post-performance

meeting between Emperor Joseph II and Mozart in which

the Emperor commented: “Too beautiful for our ears

and too many notes, my dear Mozart.” Mozart replied:

“Exactly as many as necessary, Your Majesty.”

As the young Mozart began to compose his first

operas in the mid-eighteenth century, the German

composer Christoph Willibald Gluck (1714-1787), the

art form’s second great reformer after Metastasio, had

established new rules for modern music drama. Gluck

returned to the ideals of opera’s founders, the Camerata,

and believed that opera must maintain musico-dramatic

integrity in order to remain the quintessential art form to

express human emotions and passions.

Gluck rebelled against the excesses which had seized

the existing opera seria traditions: their intricate plots,

flowery speeches, and grandiose climaxes had become

excessively ornate and superfluous, and were growing

increasingly remote from expressing a truth in the human

experience. Gluck departed from the mannerisms and

pompous artificiality of the Italians who dominated the

art form, and was seeking greater simplicity, naturalism,

and dramatic truth: he banished the excesses and abuses

of singers, as well as those florid da capo arias.

In his search for the operatic musico-dramatic ideal,

he aimed at total musical simplicity and clarity: he brought

to his music a touching musical sentiment, and a wealth

of feeling in its expression of emotion: “Restrict music

to its true office by means of expression and by following

situations of the story.”

With Gluck, the unending debate was revitalized

between supporters of the primacy of the opera libretto,

and the supporters of the primacy of the music. But in

The Marriage of Figaro Page 19

Gluck’s perception, music and text had to be integrated

into a coherent whole, nevertheless, with music serving

the poetry. With Gluck’s reforms, the lyric theater

progressed into another stage of evolution as it advanced

toward musico-dramatic maturity.

Gluck’s 46 operas, in particular, his Orfeo ed Euridice

(1762), and Alceste (1767), became the models for the

next generation of opera composers: all of his operas

were distinguished by a pronounced dramatic intensity,

enriched musical resources, a poetic expressiveness, and

an intimate connection between their music and texts.

Mozart, following Gluck, became the rejuvenator of the

opera art form during the latter half of the eighteenth

century.

M

ozart said: “Opera to me comes before everything

else.” He composed his operas in all of the existing

genres and traditions: the Italian opera seria and opera

buffa, and the German singspiel.

During Mozart’s time, the Italians set the international

standards for opera: Italian was the universal language

of music and opera, and Italian opera was what Mozart’s

Austrian audiences and most of the rest of Europe wanted

most. Therefore, even though Mozart was an Austrian,

his country part of the German Holy Roman Empire,

most of Mozart’s operas were written in Italian.

Opera seria defines the style of serious Italian operas

whose subjects and themes dealt primarily with

mythology, history, and Greek tragedy. In this genre, the

music drama usually portrayed an heroic or tragic conflict

that typically involved a moral dilemma, such as love vs.

duty, and usually resolved happily with due reward for

rectitude, loyalty, and unselfishness.

Before Mozart, opera serias (baroque) were

grandiose and elaborate productions, their cardboard-

style characters rigid and pretentious, and their scores

saturated with florid da capo arias, few ensembles, and

almost no chorus. Mozart would follow Gluck’s

guidelines and strive for more profound dramatic integrity

and break with opera seria traditions: he endowed his

opera serias with a greater fusion between recitative

and aria, with accompanied recitatives, trios and

choruses, and greater use of the orchestra.

His most renowned opera serias are Idomeneo (1781),

and his last opera, La Clemenza di Tito, “The Clemency

of Titus,” a work commissioned to celebrate the

coronation in Prague of the Emperor Leopold II as King

of Bohemia.

Opera buffa had its roots in popular entertainment:

its predecessors were the Italian commedia dell’arte and

the intermezzi. The commedia dell’arte theatrical

The Marriage of Figaro Page 20

conventions evolved during the Renaissance when

strolling players presented satire, irony, and parody about

real-life situations as they ridiculed every aspect of their

society and its institutions; they characterized humorous

or hypocritical situations involving cunning servants,

scheming doctors, and duped masters. Similarly,

intermezzi, was a style of comic entertainment performed

as an interlude between acts of dramatic plays.

Most of the characters in Beaumarchais’s original

“Figaro trilogy,” the literary basis for Rossini’s The Barber

of Seville and Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro, have

antecedents in the commedia dell’arte. Figaro is loosely

based on the commedia dell’arte character of Harlequin,

an athletic, graceful, cunning valet and ladies’ man who

claimed noble birth. Likewise, Dr. Bartolo is inspired by

the character Pantelone, a character who prides himself

on being an expert on many subjects, but one who actually

knows very little and is always caught by his own

arrogance and vanity. The Marcellina character in

Marriage is the only character not based on commedia

dell’arte: she is that old rapacious spinster inspired by

characters from classic Roman comedies.

Opera buffa, deriving from the commedia dell’arte

and intermezzi genres, was Italian comic opera that had

its first popular incarnation in Giovanni Pergolesi’s La

serva padrona (1733), a work with only three characters,

but a quintessential model of the genre: a work containing

lively and catchy tunes which underscored the antics of

a servant tricking an old bachelor into marriage.

Art expresses the soul and psyche of its times. Opera

buffa provided a convenient theatrical vehicle in which

the ideals of democracy could be expressed in art: opera

buffa became an operatic incarnation of political populism.

Whereas the aristocracy identified, and even became

flattered by the exalted personalities, gods, and heroes

portrayed in the pretentious pomp and formality of the

opera seria, opera buffa’s satire and humor provided an

arena to portray very human characters in everyday

situations, as well as an opportunity to examine and

express class distinctions and the frustrations of society’s

lower classes.

As such, opera buffa became synonymous with the

spirit of the Enlightenment and the Classical era of music:

it was enthusiastically championed by such renowned

progressives as Rousseau; its music was intrinsically

more natural, and its melodies more elegant and

emotionally restrained.

Mozart delighted in portraying themes dealing with

Enlightenment inspired ideas: he lived and composed

during those social upheavals and ideological transitions

of the late eighteenth century in which the common man

fought for his rights against the tyranny and oppression

of the aristocracies. In particular, his opera buffa, The

Marriage of Figaro, contains all of the era’s social and

The Marriage of Figaro Page 21

political overtones: it portrays servants who are more

clever than their selfish, unscrupulous, and arrogant

masters. Napoleon would later conclude that Marriage,

both the Mozart and source Beaumarchais play, were

the “Revolution in action.”

Mozart’s opera buffas range from his youthful

works, La Finta Semplici (1768) and La Finta

Giardineria (1775), to his monumental buffa classics

composed with the renowned librettist, Lorenzo Da

Ponte: The Marriage of Figaro, “Le Nozze di

Figaro,”(1786) described by both composer and librettist

as a commedia per musica, “comedy with music”; Don

Giovanni, (1787), technically an opera buffa but

designated a dramma giocoso, a “humorous drama” or

“playful play,” essentially a combination of both the

opera buffa and opera seria genres; and Così fan tutte,

“Thus do all women behave,” (1789), another blend of

the opera seria with the opera buffa for which nothing

could be more praiseful than the musicologist William

Mann’s conclusion that Così fan tutte contains “the

most captivating music ever composed.”

Nevertheless, although Mozart was writing in the

Italian opera buffa genre in the Italian language, Italians

have historically shunned his Italian works, claiming

they were not “Italian” enough; contemporary La Scala

productions of a Mozart “Italian” opera are rare events.

Mozart also composed operas in the German

singspiel genre, a style very similar to Italian opera

buffa, and generally comic opera containing spoken

dialogue instead of accompanied recitative. Mozart’s

most popular German singspiel operas are: Die

Zauberflote, “The Magic Flute,” and Die Entführung

aus dem Serail, “The Abduction from the Seraglio.”

Mozart wrote over 18 operas, among them: Bastien

and Bastienne (1768); La Finta Semplice (1768);

Mitridate, Rè di Ponto (1770); Ascanio in Alba (1771);

Il Sogno di Scipione (1772); Lucio Silla (1772); La

Finta Giardiniera (1774); Idomeneo, Rè di Creta

(1781); Die Entführung aus dem Serail (The Abduction

from the Seraglio) (1782); Der Schauspieldirektor

(1786); Le Nozze di Figaro, (The Marriage of Figaro)

(1786); Don Giovanni (1787); Così fan tutte (1790);

Die Zauberflöte (The Magic Flute) (1791); La Clemenza

di Tito (1791).

T

he Marriage of Figaro has sometimes been called

the perfect opera buffa: the most inspired Mozart

opera because of the comic effectiveness of its

underlying political and social implications.

Mozart was unequivocal about his opera objectives:

“In an opera, poetry must be altogether the obedient

daughter of the music.” Nevertheless, giving priority to

The Marriage of Figaro Page 22

the text, Mozart indeed took great care in selecting

that poetry, hammering relentlessly at his librettists to

be sure they produced words that could be illuminated

and transcended by his music. To an opera composer of

such incredible genius as Mozart, words performed

through his music can express what language alone has

exhausted.

Opera, or “music drama,” by its very nature, is

essentially an art form concerned with the emotions

and behavior of human beings: the success of an opera

lies in its ability to convey a realistic panorama of

human character intensified by the emotive power of

its music. Mozart understood his fellow human beings,

and ingeniously translated his incredible human insight

through his musical language.

As such, Mozart became the first, if not the greatest,

master of musical characterization and musical

portraiture. Like Shakespeare, he ingeniously translated

“dramatic truth”: his musical characterizations portray

complex human emotions, passions, and feelings, and

bare the souls of his characters with truthful

representations of universal humanity; in those

characterizations, one senses virtues, aspirations,

inconsistencies, peculiarities, flaws, and foibles. Mozart

virtually tells it like it is, rarely suggesting any puritanical

judgment or moralization of his characters’ behavior and

actions, prompting Beethoven to lament that in Don

Giovanni and Marriage, Mozart had squandered his

genius on immoral and licentious subjects.

Nevertheless, it is that spotlight on the individual

makes Mozart a bridge between eighteenth and nineteenth

century operas. Before Mozart, in the opera seria genre,

operas portrayed abstract emotion, many times, the

dramatic form imitating the style of the Greek theater in

which an individual’s passions and the dramatic situations

would generally transfer to the chorus for either narration,

commentary, or summation. But Mozart was anticipating

the transition to the Romantic movement that was to

begin soon after his death. His music realistically

characterizes sentiments and feelings; Mozart made opera

come alive by replacing those ancient theatrical devices

of Greek drama, discarding their masks, and portraying

individuals who possess definite, distinctive, and

recognizable musical personalities.

Mozart was therefore the first composer to perceive

clearly the vast possibilities of the operatic form as a

means of musically creating characterization: in his

operas, great and small persons move, think, and breathe

on the human level. His musical characterizations

provide extraordinary and insightful portrayals of real

and complex humanity in their conduct and character.

It is in the interaction between those characters

themselves, particularly in his ensembles, almost

symphonic in grandeur, which become moments in

The Marriage of Figaro Page 23

which an individual character’s emotions, passions,

feelings, and reactions stand out in high relief.

As a consequence, for over two-hundred years,

Mozart’s characters have captivated and become

treasures to its opera audience: Don Giovanni’s Donna

Anna, Donna Elvira, Zerlina, Masetto, Leporello, and Don

Giovanni himself; The Marriage of Figaro’s Count and

Countess, Cherubino, Susanna, and Figaro. All of these

Mozartian characters are profoundly human: they act

with passion, yet they retain a special Mozartian dignity

as well as sentiment.

In the end, like Shakespeare, Mozart’s

characterizations have become timeless representations

of humanity, great or flawed. His opera characterizations

are as contemporary in the 20th-century as they were in

the later part of the 18

th

century, even though costumes,

and even though customs may have changed. So The

Marriage’s predatory Count Almaviva, attempting to

exercise his feudal right of droit de seigneur, may be no

different than his 20

th

century counterpart: a successful,

if not arrogant executive, legally forbidden, yet desiring

to bed his illegal alien housekeeper against her wishes.

In order to portray, communicate, and truthfully

mirror the human condition, Mozart became a magician

in developing and inventing various techniques within

his unique musical language. He expresses those human

qualities not only through distinguishing melody, but also

through the specific essence of certain key signatures,

as well as through rhythm, tempo, pitch, and even

through accent and speech inflection.

As an example, each musical key inherently conveys

a particular mood and effect. In Mozart, often G major

is the key for rustic life and the common people: A major,

the seductive key for sensuous love scenes. In Don

Giovanni, D minor appears solemnly in the Overture

and its final scene: Mozart’s key for Sturm und Drang,

(storm and stress). When characters are in trouble, they

sing in keys far removed from the home key: as they get

out of trouble, they return to that key, reducing the

tension.

In both Mozart’s Don Giovanni and The Marriage

of Figaro, social classes clash on the stage with sentiment

and insight: Mozart’s musical characterizations range in

his operas from underdogs to demigods, but when he

deals with peasants and the lower classes, he is subtle,

compassionate, and loving. So Mozart’s heroes become

those bright characters who occupy the lower stations,

those Figaros, Susannas, and Zerlinas, characters whom

he ennobles with poignant musical portrayals of their

complex personal emotions, feelings, hope, sadness,

envy, passion, revenge, and eternal love.

Mozart’s theatrical genius is his ability to express

truly human qualities in music which endows his

The Marriage of Figaro Page 24

character creations with a universal and sublime

uniqueness: in the end, he achieved an incomparable

immortality for himself as well as his character creations.

T

he commission for The Marriage of Figaro was

received from Mozart’s faithful patron, Emperor

Joseph II of Austria: in its premiere year, 1786, it

experienced triumphant productions in both Vienna and

Prague, even though, quite naturally, the aristocracy

deemed Mozart’s libretto as having emanated from the

depths of vulgarity. Nevertheless, Prague was not directly

under the control of the imperial Hapsburgs, and,

therefore, censorship and restriction of underlying

elements of its story was limited, if nonexistent.

Mozart chose Lorenzo da Ponte as his librettist: that

peripatetic scholar and entrepreneur, and erstwhile crony

of the notorious Casanova de Seingalt, reputedly his

assistant for selected sections of the later Don Giovanni

libretto.

Da Ponte was born in Italy in 1749, and died in

America in 1838. He was born Emmanuel Conegliano,

converted from Judaism, and was later baptized, taking

the name da Ponte in honor of the Bishop of Ceneda. Da

Ponte would take holy orders in 1773, but seminary life

failed: his subsequent picaresque life as described in his

biography bears an uncanny resemblance to that of his

libertine romantic hero, Don Giovanni.

Da Ponte was always involved in scandals and

intrigues, at one time banished from Venice, and later

forced to leave England under threat of imprisonment

for financial difficulties. In 1805, he came to the United

States, taught Italian at Columbia University, where he

introduced the Italian classics to America, and later

became an opera impresario, who in 1825, may have

been the first to present Italian opera in the United States.

In Da Ponte’s haughty Extract from the Life of

Lorenzo Da Ponte (1819), he explains why Mozart chose

him as his inspirational poet: “Because Mozart knew very

well that the success of an opera depends, first of all, on

the poet…..that a composer, who is, in regard to drama,

what a painter is in regard to colors, can never do without

effect, unless excited and animated by the words of a

poet, whose province is to choose a subject susceptible

of variety, movement, and action, to prepare, to suspend,

to bring about the catastrophe, to exhibit characters

interesting, comic, well supported, and calculated for

stage effect, to write his recitativo short, but substantial,

his airs various, new, and well situated; and his fine verses

easy, harmonious, and almost singing of themselves…..”

Certainly, in Da Ponte’s librettos for his 3 Mozart

operas, he indeed ascribed religiously to those literary

and dramatic disciplines and qualities he so eloquently

described and congratulated himself for in his

autobiography.

The Marriage of Figaro Page 25

T

he Da Ponte-Mozart source for The Marriage of

Figaro is from the trilogy of plays written by Pierre

Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais (1732-1799), the son

of a clockmaker who initially followed in his father’s

footsteps, and was subsequently appointed clockmaker

and watchmaker to the court of Louis XV.

Beaumarchais was also a musician, a self-taught

student of guitar, flute, and harp, and also composed

works for these instruments, eventually becoming the

harp teacher to the King’s daughters. Beaumarchais

married the widow of a court official in 1756, and now

elevated to the status of a nobleman, took the name

Beaumarchais, and bought the office of secretary to the

king.

In 1763, France was still seeking revenge for its

loss of Canada, and was observing with great interest

the development of the American “resistance movement.”

In support, the French government offered covert aid to

the American rebels, but they were determined to keep

France out of the war until an opportune moment.

Nevertheless, in 1776, a fictitious company was set up

under the direction of the author Pierre Augustin Caron

de Beaumarchais, its purpose, to funnel military supplies

and sell arms to the rebellious American colonists.

Nevertheless, Beaumarchais’s fame rests on his

literary achievements: the comedic theatrical trilogy,

which includes Le Barbier de Séville, ou La précaution

inutile (1775), “The Barber of Seville, or the Useless

Precaution,” Le mariage de Figaro, ou La folle journée

(1784), “The Marriage of Figaro, or the Crazy Day,”

and the final installment, L’autre Tartuffe, ou la La Mère

Coupable, “The Guilty Mother.” (1792).

In his plays, Beaumarchais knits together a cast of

thinly disguised real heroes, lower classes characters who

survive though imagination and wit, and none more

admirable than Figaro - Beaumarchais himself – who is a

master of sabotage and intrigue, and a clever and

enterprising “man for all seasons.” Figaro is opposed by

real villains and tormentors who are in continuous conflict

with one another: his antagonists are all members of the

upper classes.

Figaro’s witty and highhanded attitude toward his

aristocratic master, Count Almaviva, in those days, a

virtual omen of revolution, is clearly defined in

Beaumarchais when Figaro speaks about the Count:

“What have you done to earn so many honors? You have

taken the trouble to be born, that’s all.”

Beaumarchais’s plays reflected the winds of change

prompted by the Enlightenment: they satirized the French

ruling class and reflected the growing lower class

dissatisfaction with the nobility in the years preceding

the French Revolution. Both Beaumarchais’s Le Barbier

de Séville and Le marriage de Figaro, in their caustic

The Marriage of Figaro Page 26

satire of prevailing social and political conditions, flatter

the lower classes, and castigate the upper class nobility.

His heroic output, “The Figaro trilogy,” or the

“Almaviva trilogy,” indeed represents an historical canvas

of late eighteenth century society. Their overflowing

social and political implications sum up an era: they became

the essential personification of the forthcoming French

Revolution, which they not only reflect, but even

influenced and inspired, and consciously or unconsciously

set into motion. In these plays, the ancien regime is seen

in declining grandeur and impending doom, prompting

Napoleon to later comment after the historical fact, that

they truly represented the “revolution already in action.”

All of the plays center around the colorful character

of the factotum Figaro, a jack-of-all-trades, whose savvy

and ingenuity serves as the symbol of class revolt against

the aristocracy. Le barbier de Séville, originally written

by Beaumarchais as an opera libretto for the Opéra-

Comique, was banned for two years before it was finally

performed in 1775, a failure at its first performance, but

catapulted to success after later revisions. The King would

briefly imprison Beaumarchais for his blasphemous

writings, but he acceded to public pressure, and to later

placate him, in an ironic twist, agreed to a gala

performance of Le barber de Seville at Versailles: his

wife, Marie-Antoinette portrayed Rosine, and the future

Charles X, portrayed Figaro.

Le marriage de Figaro was such a triumph that it

ran for eighty-six consecutive performances. Louis XVI

forbade performances of Le marriage de Figaro, but the

masses, not in a mood to be trifled with, demanded and

received performances.

Mozart’s opera based on these plays, The Marriage

de Figaro, and later, Rossini’s opera, Il Barbiere di

Siviglia, “The Barber of Seville” (1816), would eventually

assure literary immortality for Beaumarchais’s

masterpieces. Although each one of Beaumarchais’s plays

ends in a marriage, not everyone lives happily ever after:

each play seems to resolve more darker than the one

before. In Beaumarchais’s final installment, L’autre

Tartuffe, ou la La Mère Coupable, “The Guilty Mother.”

(1792), appeared one year after Mozart’s death. In that

story, the Countess Almaviva has a child by Cherubino:

one is so tempted to speculate how would Mozart have

darkened that episode with his music had he attacked an

opera on the subject.

M

ozart’s Marriage antedates Rossini’s Barber by

thirty years. Rossini’s work essentially owes its

provenance to another opera based on Beaumarchais,

Paisello’s Barbiere di Siviglia (1780), but it was Rossini’s

admiration for Mozart’s Marriage that strongly persuaded

him to create his Barber opera, a work now recognized

The Marriage of Figaro Page 27

as the greatest opera buffa ever written, as well as the

perfect companion piece to Mozart’s Marriage.

Nevertheless, in Rossini’s Barber, the political and

social undercurrents of the late eighteenth century are

understated: the French Revolution had already become

indelibly inscribed in history, and the Congress of Vienna

had just implemented a new status quo for Europe. In

fact, Rossini’s libretto was considered so inoffensive to

the aristocracy that his librettist, Cesare Sterbini, had

the approval of the Roman censor even before the

composer saw it, and the government made no effort or

pretext to suppress it.

As it turned out, opposition to Rossini’s opera was

purely personal, cloaked behind the opera public’s

devotion to the venerated Paisello, the composer of the

first Barber opera: Paisello was still alive and not yet out

of the public mind or popular affection.

These two Figaro operas are in truth appropriate

companions. Although the later Rossini work has none

of the deep and tender sentiment which underlies so much

of Mozart’s music, from a comic viewpoint, Rossini’s

work inherently deals with a more humorous phase of

the entire trilogy: the intrinsic humor, frolic, and vivacity

inherent in the Count’s adventures with Figaro while

outwitting Dr. Bartolo, and carrying off the mischievous

Rosina.

In contrast, Marriage’s story offers a depiction of

the transformation of the Count after his marriage: his

intrigues, suspicions, and philanderings. The differences

are certainly accentuated in Rossini’s Barber, where the

youthful and impetuous characters have an elemental

freshness, but in Mozart, they have matured, become

domesticated, and certainly have transcended youthful

innocence. Nevertheless, these two operas are “marriages

made in operatic heaven.”

In addition to Mozart and Rossini, Beaumarchis’s

comedies were set to opera in Friedrich Ludwig Benda’s

Der Barbier von Sevilla; Paerrs’s Il nuovo Figaro; and

of course, in Paisello’s The Barber of Seville.

B

eaumarchais’ heroic output “The Figaro trilogy,” or

the “Almaviva trilogy,” deal with despicable aspects

of human character whose transformations were the very

focus of Enlightenment idealism, and the undercurrent

which precipitated the French Revolution itself.

The engines that drive the plots of The Marriage of

Figaro - and Don Giovanni - are the moral foibles and

peccadillos of aristocratic men: Count Almaviva and

Don Giovanni are the nobility, men who can almost be

perceived by modern standards as criminals; men who

are unstable, wildly libidinous, and men who feel

themselves above moral law. Both works focus on

seduction; seduction that ends in hapless failure.

The Marriage of Figaro Page 28

The Marriage of Figaro has proven to be a

monument to Mozart’s genius in musical

characterization: it is considered one of the greatest

masterpieces of comedy in music with melodies that are

enormously faithful to character and situation, contain

charm, a perfection of form, and an utter spontaneity.

Moreover, the music sparkles with all the wit and gaiety

of Beaumarchais’s humorous work, and certainly, only

praise can be granted to Da Ponte’s shrewdly contrived

libretto.

The class conflicts and their social and political

realities, all unite and blend into a highly sophisticated

battle of the sexes. The Marriage story takes place three

years after the Barber story: the Count has now become

a predatory philanderer. Rosina, now the Countess,

displays mature wisdom well beyond her youthful years.

Figaro is to marry Susanna. The entire action revolves

around the Count’s obsession to seduce Susanna, even

though he has abandoned his right of droit de signeur.

Figaro and Susanna are determined to marry before the

Count can force the issue.

Nevertheless, the lower classes refuse to be

victimized: through their wiles, wit, determination,

decency and love – and a little bit of luck - they can tip

the scales against upper class arrogance and power. In

these comic plays, characters become divinely articulate

harbingers of revolution. Da Ponte removed what he

considered politically offensive in Beaumarchais’s

original: Mozart replaced them with his music.

Nevertheless, class relations are presented as they

are, the underlying implication that social hierarchies are

accidents of fortune rather than reflections of native

worth: these themes are clearly woven into both the

literary as well as the musical fabric of Marriage.

T

he two main female characters in Marriage, Susanna

and the Countess, are represented with brilliantly

contrasting characterizations. In Mozart’s later Don

Giovanni, he would likewise provide a profound musical

portrayal of diverse femininity in the complimentary

characterizations of Donna Anna, Donna Elvira, and

Zerlina.

Susanna is indeed the heroine of the story: she is

multidimensional and complex, and possesses a high

degree of instinctive intelligence. Like her “Columbina”

forebears from the commedia dell’arte, and even Rosina

from Beaumarchais’s Barbier, she is a spirited character;

sharp-witted, spunky and wily, and far from a soubrette,

or one of those archetypal, pert, cunning, and scheming

servants. She radiates with assuredness and omniscience,

whether in her conversations with the Countess, or in

the third act when she fights off victimization by the

lascivious Count: her sense of honor dominates her

The Marriage of Figaro Page 29

actions, and she proves to be the one character in the

opera who is stable and capable of sorting out

everybody’s troubles as well as her own.

Susanna becomes the master of irony in the

magnificent comic finale of Act II when she emerges

from the closet, commenting with feigned

disingenuousness and masterful irony: “What is this

excitement about. A drawn sword? To kill the page. And

it’s only me after all!”

From the very beginning, she demonstrates her

intuitive intelligence and insight, making sure Figaro

directs his attention to her wedding hat, and certainly,

opening his eyes to the Count’s ulterior motives in

placing their room so close to his quarters. But it is in

the last act, when Mozart provides her with that lovely,

subdued, and sensual aria, Deh viene non tardar, that

she overwhelms Figaro with her display of great depth

and feeling. Just like the Countess’s two great arias in

which she movingly expresses resignation, so too does

Susanna reveal intense tenderness and emotion. Susanna’s

Deh viene non tardar is a magnificent moment in the

opera when action and time stops, and one senses her

anticipation of her future: a sense of liberty and freedom

for her and Figaro, and a dream of a sublimely happy

future together.

That other great Mozartian character in The Marriage

is the Countess, a seemingly pathetic woman, wounded

and prone to melancholy, but always exuding a profound

spiritual and moral presence. Her dignity has been pitifully

injured by the Count, but she never at anytime considers

staining his honor by vengefully taking a lover.

Subconsciously, she understands, but consciously will

not accept, her husband’s philandering: a man seemingly

bored by his wife; who in today’s terms, would be

considered the classic victim of a massive mid-life crises.

The Countess’s profound dignity is magnifiently

conveyed in her two arias: Dov’e sono, and Porgi amor:

Da Ponte’s words are heartfelt expressions from a truly

noble and aristocratic woman, but it is the emotive power

of Mozart’s music that reflects her true feelings and

genuine pathos.

T

he finale of Act II is perhaps one of Mozart’s most

monumental musical inventions and designs, an

episode of some 150 pages of score without parallel in

opera; its 20 minute length virtually makes it a play itself.

Mozart continuously uses a variety of key changes to

alter the mood and provide surprise upon surprise.

Eventually, eight characters appear on stage, and the

ensemble builds steadily, never with a false climax or

inconsistent or artificial stroke.

The Act II finale sequence demonstrates the

The Marriage of Figaro Page 30

complexity of the opera’s essence: misunderstandings

Who is in the Countess’s closet? (Is it Cherubino as

both the Count and Countess presume?) What are the

contents of the dropped paper? (Figaro has to be primed

by Susanna through the Countess to know it is

Cherubino’s commission.) Who arranged for a nocturnal

rendezvous? (The Count’s obsession to know who wrote

the anonymous rendezvous note)

The ensemble is inaugurated when the Count,

convinced that Cherubino is having an affair with the

Countess and is hiding in the closet, begins to break down

the closet door. The only two characters on stage, the

Count and the Countess, begin an acrimonious exchange:

the Count erupts in rage, and becomes overbearing and

intolerably aggressive; the Countess becomes flustered

and attempts to reason with him and persuades him of

her innocence, but compounds the situation by admitting

that Cherubino is in the closet - and only half dressed.

The first surprise – to both the Count and Countess

- is the emergence of Susanna, not Cherubino, from the

closet. Out of necessity, and recognizing a

misunderstanding, the Count calms down, and asks his

wife’s forgiveness.

With Figaro’s arrival, the ensemble group builds to

four characters. The Count, suspicious and confused,

decides to question his wily valet, instinctively

condemning him for being involved in the anonymous

note he received. And then the group becomes a quintet

when the gardener Antonio arrives to announce that

someone jumped out the window and ruined his flower

bed.

The comic confusion augments and reaches a climax

with the entrance of Don Basilio, Dr Bartolo, and

Marcellina, the latter arriving to claim that Figaro must

marry her as payment for his debt to her.

In this ensemble, all eight characters are on stage

singing individually, and also in ensemble. Through

Mozart’s genius, the ensemble fuses like a symphony,

the music creating a new drama of sensibilities and

underlying subtleties and truths which transcend the

libretto. Mozart emphatically highlights each surprise and

revelation with a change in key, rhythm, and tempo. As

such, one feels and senses the shock, nevertheless, the

sequence maintains its delicacy and playfulness, always

hinting that new revelations lie beyond what is known.

No one before Mozart had attempted such a long,

uninterrupted piece of operatic music. Mozart proved

that he was incredibly innovative: composers in the

eighteenth century traditionally wrote short numbers, all

strung together with recitatives or spoken dialogues. But

in this second-act finale, with its seven musical numbers