Association Between Sexual Behavior

and Cervical Cancer Screening

Anthony M.A. Smith, Ph.D.,

1

Wendy Heywood, B.A. (Hons),

1

Richard Ryall, B.App.Sc. (Hons),

1

Julia M. Shelley, Ph.D.,

1,2

Marian K. Pitts, Ph.D.,

1

Juliet Richters, Ph.D.,

3

Judy M. Simpson, Ph.D.,

4

and Kent Patrick, Ph.D.

1

Abstract

Background: Not much is known about whether women who follow Pap testing recommendations report the

same pattern of sexual behavior as women who do not.

Methods: Data come from part of a larger population-based computer-assisted telephone survey of 8656 Aus-

tralians aged 16–64 years resident in Australian households with a fixed telephone line (Australian Longitudinal

Study of Health and Relationships [ALSHR]). The main outcome measure in the current study was having had a

Pap test in the past 2 years.

Results: Data on a weighted sample of 4052 women who reported sexual experience (ever had vaginal inter-

course) were analyzed. Overall, 73% of women in the sample reported having a Pap test in the past 2 years.

Variables individually associated with Pap testing behavior included age, education, occupation, cohabitation

status, residential location, tobacco and alcohol use, body mass index (BMI), lifetime and recent number of

opposite sex partners, sexually transmitted infection (STI) history, and condom reliance for contraception. In

adjusted analyses, women in their 30s, those who lived with their partner, and nonsmokers were more likely to

have had a recent Pap test. Those who drank alcohol at least weekly were more likely to have had a recent test

than irregular drinkers or nondrinkers. Women with no sexual partners in the last year were less likely to have

had a Pap test, and women who reported a previous STI diagnosis were more likely to have had a Pap test in the

past 2 years.

Conclusions: There are differences in Pap testing behavior among Australian women related to factors that may

affect their risk of developing cervical abnormalities. Younger women and regular smokers were less likely to

report a recent test. Screening programs should consider the need to focus recruitment strategies for these

women.

Introduction

P

articipation in Papanicolaou (Pap) Screening

has

been associated with a number of sociodemographic

characteristics, although not consistently.

1–12

Little research

has investigated interval between Pap tests and sexual be-

havior, however, which is surprising, given the primary cause

of cervical cancer is sexually acquired persistent human

papillomavirus (HPV).

13–16

In the United States, having had a

Pap test in the past year was more common among women

reporting one of the following: being £ 15 years at first sex,

having ‡ 10 lifetime sex partners, having a history of pelvic

inflammatory disease (PID), having a history of sexually

transmitted disease (STD), and with male sexual partners

having sex with other women in the past 12 months.

3

A Swedish study interviewed women on a cytology register,

finding that women with two or more sex partners during the

last 5 years were more likely to have had a recent Pap test,

whereas age at first sex and total number of sex partners were

not associated with screening. Not being screened was posi-

tively associated with the nonuse of oral contraceptives and

frequent condom use.

2

Having two or more sex partners was

associated with Pap testing in the last 3 years in a Spanish

study, although age at first sex was not.

17

Finally, a recent U.S.

1

Australian Research Centre in Sex, Health & Society, La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia.

2

School of Health and Social Development, Deakin University, Melbourne, Australia.

3

School of Public Health and Community Medicine, University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia.

4

Sydney School of Public Health, University of Sydney, Australia.

JOURNAL OF WOMEN’S HEALTH

Volume 20, Number 7, 2011

ª Mary Ann Liebert, Inc.

DOI: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2585

1091

study found women in same-sex relationships were less likely

to have had a Pap test in the last 3 years than were women in

relationships with men.

18

Given the importance of regular cervical screening and the

paucity of research on and inconsistency of findings about the

relationship between having a recent Pap test and sexual and

behavioral factors, further examination of this topic is essen-

tial. Here, we examine if women who report their last Pap test

as being no more than 2 years ago (the Australian recom-

mendation for Pap testing is every 2 years once sexually ac-

tive

19

) report the same patterns of sociodemographic and

behavioral characteristics, including sexual behavior, as do

women reporting longer time since their most recent

test. In Australia, all or part of the costs associated with Pap

testing are subsidized by the universal healthcare system,

Medicare.

20

Materials and Methods

Recruitment

The present study was a component of the Australian

Longitudinal Study of Health and Relationships (ALSHR).

21

The aim of the ALSHR was to document the natural history of

sexual and reproductive health of the Australian adult pop-

ulation. To be able to identify a statistically significant relative

risk of approximately 2.0 when exposures have a prevalence

of at least 10%–20% and outcomes have an incidence over 3

years of at least 2%–4.5%, the ALSHR surveyed 4290 men and

4366 women in all states and territories of Australia. Only

women who reported sexual experience (ever had vaginal

intercourse), the target population for regular Pap testing,

were included in the current analysis.

Survey

Women were asked a range of sociodemographic ques-

tions, including age, education, occupation, cohabitation sta-

tus, residential location, language spoken at home, country of

origin, and frequency of use of tobacco and alcohol. Because

of previously reported associations between body mass index

(BMI) and Pap testing,

1,6,7

BMI, calculated as weight in kilo-

grams divided by height in meters squared, was investigated

using self-reported weight and height. Four categories cor-

responding to current World Health Organization (WHO)

recommendations were used: underweight, BMI < 18.5 kg/m

2

;

normal weight, BMI = 18.5–24.9 kg/m

2

; overweight, BMI =

25–29.9 kg/m

2

; obese, BMI ‡ 30 kg/m

2

.

22

Potential variables of interest were sexual identity (het-

erosexual, homosexual/lesbian, bisexual), age at first vaginal

intercourse, lifetime number of opposite sex sexual partners

(any form of sexual experience), and number of opposite sex

sexual partners in the year before the interview (any form of

sexual experience). Additional variables, including history of

sexually transmitted infections (STIs) (self-reported diagnosis

of chlamydia, genital herpes, genital warts, syphilis, gonor-

rhea, PID, bacterial vaginosis, trichomoniasis, or crablice) and

current reliance on condoms for contraception, were also in-

vestigated because of associations with Pap testing in past

research.

2,3

Finally, Pap testing behavior was assessed by two ques-

tions: if the woman had ever had a Pap test or Pap smear, and,

if so, at what age she had her most recent Pap test. Using these

two questions and the respondent’s current age, we derived

a binary variable indicating whether the women had had a

Pap test in the previous 2 years. A 2-year cutoff was se-

lected as being consistent with Australian cervical screening

guidelines.

19

Procedure

Approval for this study was granted by the human research

ethics committees of La Trobe University, the University of

New South Wales, and Deakin University and was conducted

during 2004 and 2005 using computer-assisted telephone in-

terviewing. Participants were first contacted through random

digit dialing and, after having the study explained to them,

either gave their verbal consent to be interviewed or refused.

Of those contacted, 56.0% agreed to participate. Age was

the only selection criterion used in this study, with partici-

pants interviewed only if aged between 16 and 64 years.

Where two or more eligible respondents lived in a household,

one was randomly chosen to be interviewed. All interviews

were conducted in English.

Data analysis

All frequencies were weighted by household size and

rounded to the nearest integer. Chi-square tests were used to

assess bivariate associations between Pap testing in the past 2

years and demographic characteristics, age at first vaginal

intercourse, number of lifetime opposite sex partners, number

of opposite sex partners in the last year, STI history, and

condom reliance. Variables were included in the initial mul-

tivariate logistic regression model only if bivariate analysis

gave p < 0.25.

23

The least significant variables were sequen-

tially removed from the model until all remaining variables

were statistically significant at p < 0.05. Removed variables

were then checked one at a time to ensure they were not

significant in the final model. All analyses were weighted by

household size. p values reported are for design-based F sta-

tistics from the weight-adjusted chi-square tests (unadjusted)

and Wald tests (adjusted) of the overall effect of each factor.

All associations between variables are reported as relative

risk (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) estimated from

log-binomial regression. Log-binomial was used instead of

logistic regression as odds ratios (ORs) overstate the RR when

the outcome of interest is common ( > 10%), as is the case for

Pap testing.

24

Analyses were conducted using Stata, version

10.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Of the 4366 women who completed the survey, 4236 indi-

cated they had ever had vaginal intercourse. A further 40

women were excluded because of invalid answers to the two

Pap test questions. After these exclusions, the following ana-

lyses are based on a weighted sample of 4052 women, 2969

(73%) of whom reported having a Pap test in the previous

2 years.

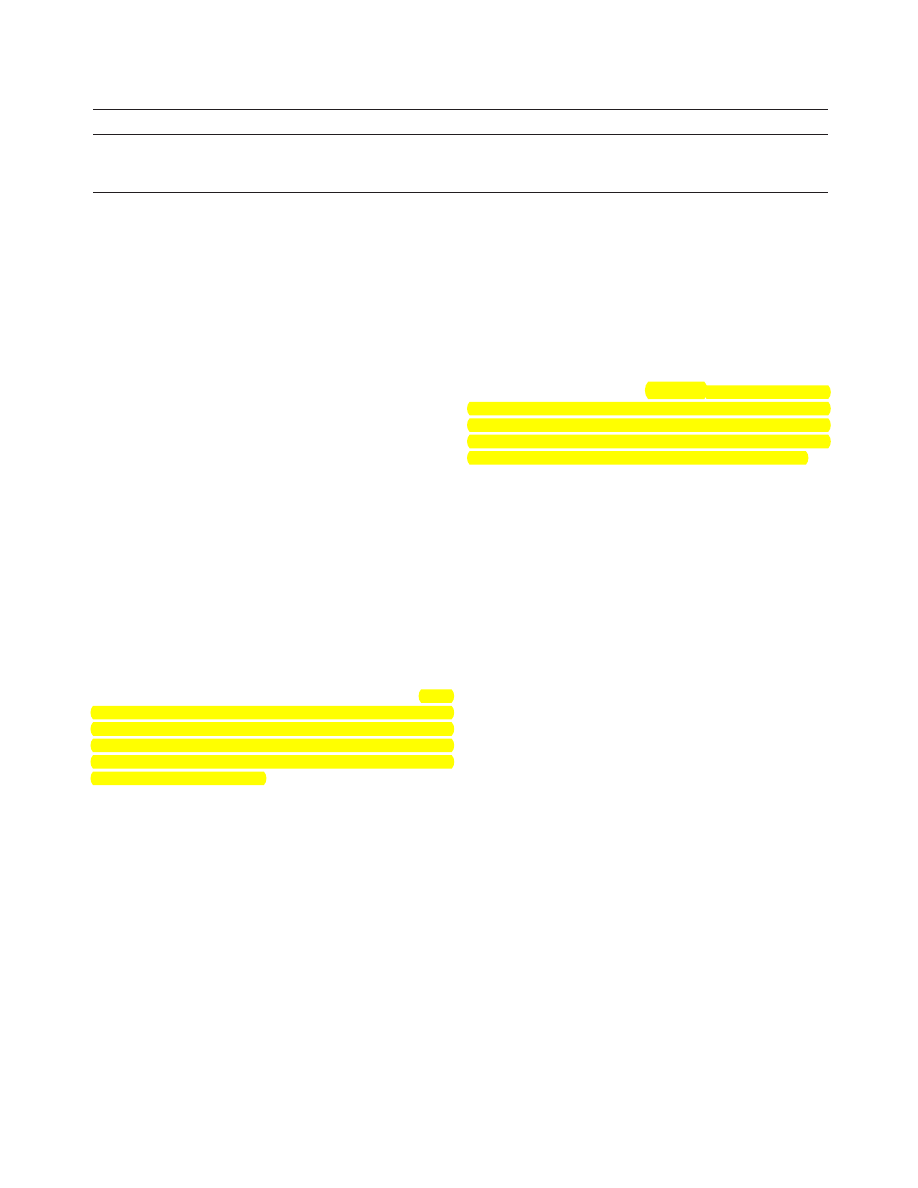

Sociodemographic and lifestyle factors

Table 1 displays the percentage and number of women

from each sociodemographic background who reported

having a Pap test in the last 2 years. In bivariate analyses, age

was strongly associated with recent Pap testing. In addition,

1092

SMITH ET AL.

Table

1. Association Between Having a Pap Test in Previous 2 Years and Demographic, Lifestyle,

and Sexual Behavior Correlates

Total n

Yes %

Unadjusted RR (95% CI)

a

Adjusted RR (95% CI)

b

Age

c

p < 0.001

p < 0.001

16–19

176

28

0.39 (0.30-0.51)

0.36 (0.26-0.48)

20–29

633

76

0.92 (0.87-0.96)

0.92 (0.87-0.97)

30–39

943

85

-

-

40–49

1059

82

0.96 (0.93-1.00)

0.96 (0.93-0.99)

50–59

950

65

0.77 (0.73-0.81)

0.78 (0.74-0.82)

60–64

291

54

0.64 (0.58-0.71)

0.66 (0.60-0.74)

Level of education

p < 0.001

p = 0.88

Less than secondary

1113

68

-

-

Secondary/college

1927

73

1.08 (1.04-1.14)

1.01 (0.97-1.05)

Postsecondary

1012

79

1.15 (1.09-1.21)

0.99 (0.95-1.04)

Occupation

p < 0.001

p = 0.09

Professional

1393

77

-

-

Associate professional

1566

76

1.00 (0.96-1.04)

0.99 (0.95-1.03)

Tradesperson

175

70

0.92 (0.84-1.02)

0.97 (0.89-1.06)

Unskilled

844

65

0.87 (0.83-0.92)

0.96 (0.91-1.01)

Cohabitation status

c

p < 0.001

p = 0.006

Live together

2845

78

-

-

Live separately

452

68

0.90 (0.84-0.96)

0.96 (0.90-1.03)

No regular partner

756

60

0.81 (0.76-0.86)

0.90 (0.84-0.98)

Residential location

p = 0.03

p = 0.13

Metropolitan

2023

75

-

-

Regional/remote

1983

72

0.96 (0.93-1.00)

0.98 (0.95-1.01)

Language spoken at home

p = 0.34

p = 0.05

English

3904

73

-

-

Other

148

69

0.93 (0.84-1.04)

0.91 (0.81-1.02)

Country of origin

p = 0.32

p = 0.15

Australia

3188

74

-

-

Overseas

865

72

0.97 (0.93-1.01)

0.96 (0.92-1.00)

Tobacco use

c

p < 0.001

p < 0.001

None

3101

75

-

-

Less often than weekly

61

79

1.05 (0.92-1.19)

1.00 (0.90-1.11)

Weekly to daily

891

68

0.92 (0.87-0.96)

0.90 (0.86-0.95)

Alcohol use

c

p < 0.001

p = 0.006

None

986

69

-

-

Less often than weekly

1396

73

1.05 (1.00-1.10)

1.05 (1.00-1.10)

Weekly to daily

1669

76

1.10 (1.05-1.15)

1.08 (1.03-1.13)

Body mass index

p = 0.008

p = 0.26

Underweight

170

68

0.90 (0.81-1.00)

1.01 (0.92-1.11)

Normal

1941

75

-

-

Overweight

1089

75

0.98 (0.94-1.02)

1.01 (0.97-1.05)

Obese

740

69

0.90 (0.86-0.95)

0.95 (0.91-1.00)

Sexual identity

p = 0.19

p = 0.31

Heterosexual

3961

73

-

-

Homosexual

36

65

0.92 (0.71-1.19)

0.97 (0.72-1.31)

Bisexual

55

62

0.84 (0.68-1.03)

0.90 (0.72-1.12)

Age at first vaginal sex

p = 0.61

p = 0.72

< 16 years

581

72

-

-

‡ 16 years

3471

73

1.00 (0.95-1.05)

1.00 (0.96-1.05)

Lifetime number of opposite sex partners

p < 0.001

p = 0.15

1

987

68

-

-

2–5

1610

72

1.06 (1.01-1.11)

1.03 (0.98-1.08)

6–10

773

78

1.13 (1.07-1.20)

1.04 (0.99-1.10)

11 +

533

79

1.14 (1.08-1.21)

1.04 (0.98-1.11)

Number of opposite sex partners in last year

c

p < 0.001

p = 0.04

0

623

60

0.78 (0.73-0.84)

0.91 (0.84-0.99)

1

3139

76

-

-

2 +

276

70

0.94 (0.87-1.02)

1.00 (0.93-1.08)

STI history

c

p < 0.001

p = 0.004

No

3342

72

-

-

Yes

710

80

1.09 (1.05-1.14)

1.06 (1.02-1.09)

(continued)

CERVICAL SCREENING AND SEXUAL BEHAVIOR

1093

education, occupation, cohabitation status, residential loca-

tion, frequency of tobacco and alcohol use, and BMI were all

individually associated with having had a Pap test in the last

2 years.

The final multivariate model contained age, cohabitation

status, tobacco use, alcohol use, number of opposite sex

partners in the last year, and STI history. Although number of

opposite sex partners was initially removed from the model

because of nonsignificance, it became significant when added

back into the final model and was, therefore, retained. In

multivariate analysis, younger and older women were less

likely to have had a Pap test than women in their 30s. Those

without a regular partner were also less likely to have had a

recent Pap test, as were women who smoked regularly.

Conversely, women who drank alcohol regularly were more

likely to have had a Pap test than women who did not drink.

Sexual behavior and Pap testing

In bivariate analysis, sexual identity, age at first sex, and

current reliance on condoms were not associated with having

a Pap test in the past 2 years, whereas lifetime number of sex

partners, number of sex partners in the past 12 months, and

STI history were associated with Pap testing (Table 1). After

taking into account significant sociodemographic and sexual

behavior variables, women reporting no sexual partners in the

previous year were less likely to have had a recent Pap test,

and those reporting at least one diagnosed STI were more

likely to have had a Pap test.

Finally, we expected there would be a strong relationship

between number of lifetime sexual partners and number of

sexual partners in the last year. We, therefore, calculated ad-

justed RRs for lifetime number of partners with ( p = 0.15) and

without adjusting for number of partners in the last year

( p = 0.11). Overall, this made little difference to the signifi-

cance of the factors, the adjusted RRs, and CIs (data not

shown). For consistency with other excluded variables, life-

time number of partners was adjusted for all variables sig-

nificant in the final model, including number of sexual

partners in the last year.

Discussion

Age, cohabitation status, tobacco and alcohol use, number

of opposite sex partners in the last year, and a history of STIs

were all associated with whether a women had a Pap test in

the previous 2 years. Compared with women aged 30–39

years, all other age groups were less likely to have had a Pap

test. Lower screening rates among younger women are not

unique to Australia; in England in 2005, < 50% of women

aged 20–24 who were eligible for screening had had a Pap test

in the last 5 years.

25

Furthermore, research has demonstrated

a fall in screening among younger women in developed

countries in recent years.

26,27

Women > age 50 also received

less frequent tests or had stopped screening early. This was

found despite current guidelines in Australia recommending

women should not cease screening until the age of 70 and only

if they have had two normal tests within the last 5 years.

19

Women with no regular heterosexual partner were less

likely to have been screened in the last 2 years than those who

lived with their partner. Interestingly, women who drank

regularly were more likely to have had a Pap test, whereas

those who smoked regularly were less likely to have had a

Pap test in the last 2 years. Lower levels of Pap testing among

smokers is of some concern, given that smoking increases the

risk of progression of cervical abnormalities by causing ad-

ditional damage to cells already damaged by HPV.

15

Al-

though there has been concern expressed about access to Pap

testing services in rural and regional areas of Australia,

12

we

did not find any differences in likelihood of women having

had a recent test based on their residential location after ad-

justing for confounding factors, nor did we find differences

related to socioeconomic status (education and occupation)

or sexual identity. This likely reflects universal access to

healthcare in Australia.

20

Number of recent sexual partners was associated with Pap

testing over and above the influence of sociodemographic

factors. Women who had not been sexually active in the last

year with a male partner reported lower levels of Pap testing

than women with only one partner, suggesting women who

were not currently sexually active may not be being tested

regularly. Furthermore, there was not a strong association be-

tween number of sexual partners in the last year and lifetime

number of sexual partners. More research is needed to clarify

the relationship between Pap testing and number of sexual

partners, given that risk of acquiring HPV and cervical ab-

normalities increases through having more sexual partners.

15

Consistent with previous research,

3

women with a history

of STIs were more likely to have had a Pap test in the previous

2 years. It was important to investigate STI history, as it has

been suggested that STIs, such as Chlamydia infection, lead to

cervical inflammation, which could potentially facilitate a

concurrent HPV infection to become persistent, increasing the

chance of cervical cancer.

15

It is possible, however, that being

diagnosed with an STI was a result of coming for a Pap test

rather than being a characteristic of women more likely to

present for Pap testing.

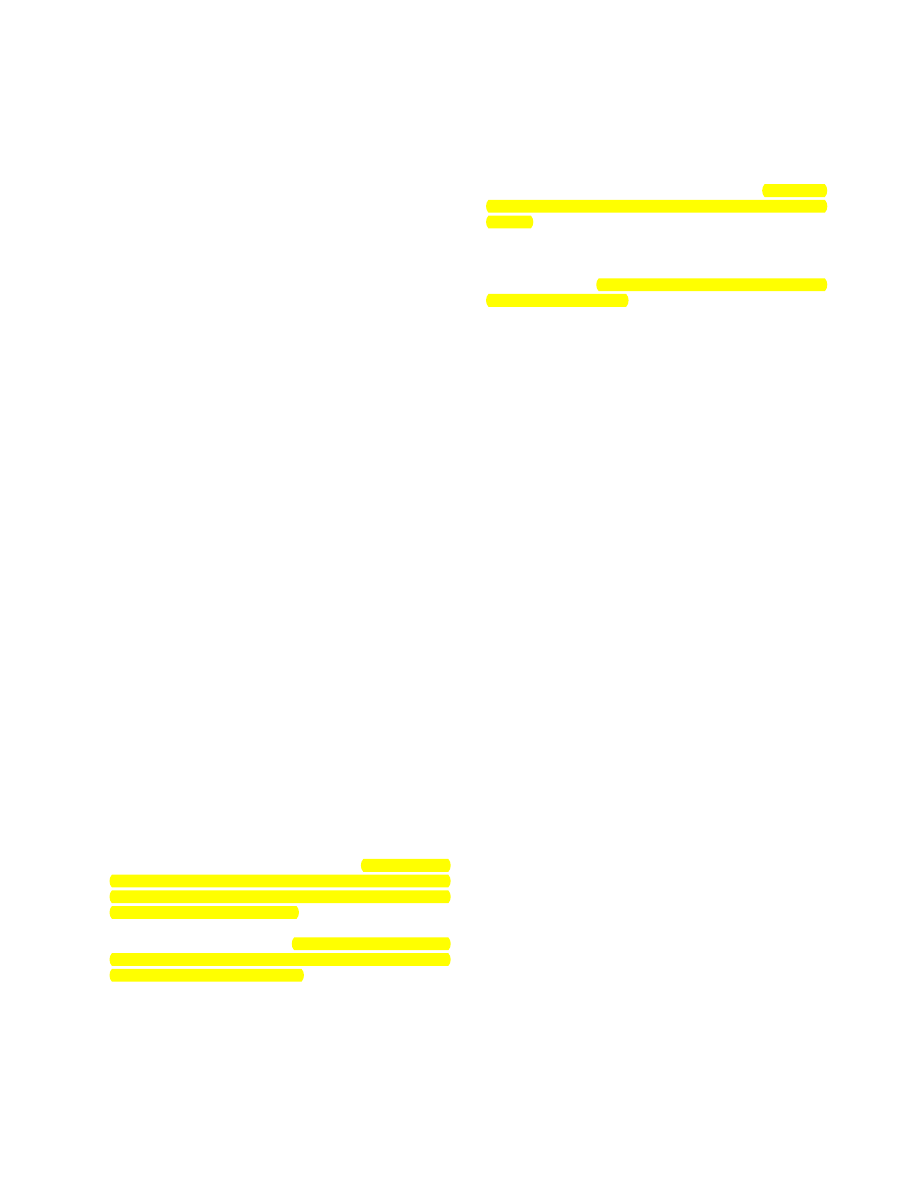

Table

1. (Continued)

Total n

Yes %

Unadjusted RR (95% CI)

a

Adjusted RR (95% CI)

b

Condom reliance for contraception

p = 0.11

d

p = 0.63

No

3533

73

-

-

Yes

520

77

1.08 (1.04-1.14)

0.99 (0.95-1.04)

a

Unadjusted relative risk (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for having a Pap test in the previous 2 years vs. not having a Pap test.

b

Adjusted RR and 95% CI for having a Pap test in the previous 2 years vs. not having a Pap test. Adjusted for age group, cohabitation

status, frequency of tobacco and alcohol use, number of opposite sex partners in the last year, and history of sexually transmitted infections.

c

Variable significant in final model.

d

Discrepancies between p values and CIs arise because p values are from chi-square tests and RR and their 95% CIs are from log-binomial

regression.

STI, sexually transmitted infection.

1094

SMITH ET AL.

Finally, age at first sex was investigated, as it has been

linked to increased risk of acquiring HPV, either through being

an indicator for future high-risk sexual behavior or because of

greater vulnerability during adolescence.

15,28

Our findings are

consistent with past studies that have found no association

between age at first sex and Pap testing behavior.

2,17

The present study has a number of strengths and weak-

nesses. Strengths of the study were its large sample size and

wide age range. Our sample included women from nearly all

age groups that are recommended to receive Pap testing in

Australia. Limitations include the reliance on self-report and

possible social desirability bias. Recent systematic reviews

and meta-analyses of studies investigating the accuracy of

self-reports of Pap testing compared to medical records have

found women overreport their participation in screening over

a given time frame.

29,30

Furthermore, our study says nothing

about intervals between Pap tests, only time since last Pap

test, nor does the study comment on Pap testing and same sex

partners. Finally, although the response rate may be relatively

low (56%), this should not influence findings about Pap test-

ing behavior. Similar sampling procedures have been shown

to produce representative samples in previous studies.

31

It is

possibly, however, that compliant individuals are more likely

to both complete surveys and receive healthcare screening,

such as Pap testing.

This study demonstrates that certain groups of Australian

women are vulnerable to not receiving Pap tests within the

recommended time frame, every 2 years once sexually active.

Furthermore, it demonstrates that sexual behaviors have an

impact on whether a Pap test had been conducted in the past 2

years beyond previously reported sociodemographic factors.

Screening programs should consider the need to focus re-

cruitment strategies for these women, particularly younger

women, older women, and regular smokers.

Acknowledgments

The study was funded by the National Health and Medical

Research Council through grants 234409 and 487304. We

thank Jason Ferris for assistance with data management and

the Hunter Valley Research Foundation for data collection.

Disclosure Statement

No completing financial interests exist.

References

1. Blackwell DL, Martinez ME, Gentleman JF. Women’s com-

pliance with public health guidelines for mammograms and

Pap tests in Canada and the United States: An analysis of

data from the Joint Canada/United States Survey of Health.

Womens Health Issues 2008;18:85–99.

2. Eaker S, Adami HO, Sparen P. Reasons women do not at-

tend screening for cervical cancer: A population-based study

in Sweden. Prev Med 2001;32:482–491.

3. Hewitt M, Devesa S, Breen N. Papanicolaou test use among

reproductive-age women at high risk for cervical cancer:

Analyses of the 1995 National Survey of Family Growth. Am

J Public Health 2002;92:666–669.

4. Hewitt M, Devesa SS, Breen N. Cervical cancer screening

among U.S. women: Analyses of the 2000 National Health

Interview Survey. Prev Med 2004;39:270–278.

5. Luengo Matos S, Munoz van den Eynde A. Use of Pap

smear for cervical cancer screening and factors related with

its use in Spain. Aten Primaria 2004;33:229–234.

6. Maruthur NM, Bolen SD, Brancati FL, Clark JM. The asso-

ciation of obesity and cervical cancer screening: A systematic

review and meta-analysis. Obesity 2008;17:375–381.

7. Nelson W, Moser RP, Gaffey A, Waldron W. Adherence

to cervical cancer screening guidelines for US women aged

25–64: Data from the 2005 Health Information National

Trends Survey (HINTS). J Womens Health 2009;18:1759–

1768.

8. Ortiz AP, Hebl S, Serrano R, Fernandez ME, Suarez E,

Tortolero-Luna G. Factors associated with cervical cancer

screening in Puerto Rico. Prev Chronic Dis 2010;7:A58.

9. Peterson NB, Murff HJ, Cui Y, Hargreaves M, Fowke JH.

Papanicolaou testing among women in the Southern United

States. J Womens Health 2008;17:939–946.

10. Selvin E, Brett KM. Breast and cervical cancer screen-

ing: Sociodemographic predictors among white, black,

and Hispanic women. Am J Public Health 2003;93:

618–623.

11. Siahpush M, Singh GK. Sociodemographic predictors of Pap

test receipt, currency and knowledge among Australian

women. Prev Med 2002;35:362–368.

12. Wain G, Morrell S, Taylor R, Mamoon H, Bodkin N. Var-

iation in cervical cancer screening by region, socio-economic,

migrant and indigenous status in women in New South

Wales. Aust NZ J Obstet Gynaecol 2001;41:320–325.

13. Bosch FX, Lorincz A, Munoz N, Meijer C, Shah KV. The

causal relation between human papillomavirus and cervical

cancer. J Clin Pathol 2002;55:244–264.

14. Franco EL, Rohan TE, Villa LL. Epidemiologic evidence and

human papillomavirus infection as a necessary cause of

cervical cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 1999;91:506–511.

15. Trottier H, Franco EL. The epidemiology of genital human

papillomavirus infection. Vaccine 2006;24:4–15.

16. Walboomers JMM, Jacobs MV, Manos MM, et al. Human

papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical

cancer worldwide. J Pathol 1999;189:12–19.

17. de Sanjose S, Corte´s X, Me´ndez C, et al. Age at sexual ini-

tiation and number of sexual partners in the female Spanish

population: Results from the AFRODITA survey. Eur J Ob-

stet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2008;140:234–240.

18. Buchmueller T, Carpenter CS. Disparities in health insurance

coverage, access, and outcomes for individuals in same-sex

versus different-sex relationships, 2000–2007. Am J Public

Health 2010;100:489–495.

19. Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing.

National Cervical Screening Program, 2009 Available at www

.cancerscreening.gov.au/internet/screening/publishing

.nsf/Content/NCSP-Policies-1 Accessed September 6,

2010.

20. Biggs A. Medicare. Background brief. Parliamentary Li-

brary, Parliament of Australia, 2003. Available at aph.gov

.au/library/intguide/SP/medicare.htm Accessed February

16, 2011.

21. Smith AMA, Pitts MK, Shelley JM, Richters J, Ferris J. The

Australian Longitudinal Study of Health and Relationships.

BMC Public Health 2007;7:139.

22. World Health Organization. Global database on body mass

index, 2006 Available at apps.who.int/bmi/index.jsp Ac-

cessed August 19, 2009.

23. Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied logistic regression. New

York: John Wiley, 1989.

CERVICAL SCREENING AND SEXUAL BEHAVIOR

1095

24. McNutt LA, Wu C, Xue X, Hafner JP. Estimating the relative

risk in cohort studies and clinical trials of common out-

comes. Am J Epidemiol 2003;157:940–943.

25. Lancuck L, Patnick J, Vessey M. A cohort effect in cervical

screening coverage? J Med Screen 2008;15:27–29.

26. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Cervical screen-

ing in Australia 2006–2007. Canberra: AIHW, 2009.

27. Lancucki L, Fender M, Koukari A, et al. A fall-off in cervical

screening coverage of younger women in developed coun-

tries. J Med Screen 2010;17:91–96.

28. Kahn JA, Rosenthal SL, Succop PA, Ho GYF, Burk RD.

Mediators of the association between age of first sexual in-

tercourse and subsequent human papillomavirus infection.

Pediatrics 2002;109:e5.

29. Howard M, Agarwal G, Lytwyn A. Accuracy of self-reports

of Pap and mammography screening compared to medical

record: A meta-analysis. Cancer Causes Control 2009;

20:1–13.

30. Rauscher GH, Johnson TP, Cho YI, Walk JA. Accuracy of

self-reported cancer-screening histories: A meta-analysis.

Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2008;17:748–757.

31. Smith AMA, Rissel CE, Richters J, Grulich AE, Visser RO.

Sex in Australia: The rationale and methods of the Austra-

lian Study of Health and Relationships. Aust N Z J Public

Health 2003;27:106–117.

Address correspondence to:

Anthony M.A. Smith, Ph.D.

Australian Research Centre in Sex, Health & Society

La Trobe University

215 Franklin Street

Melbourne, Victoria 3000

Australia

E-mail: anthony.smith@latrobe.edu.au

1096

SMITH ET AL.

Copyright of Journal of Women's Health (15409996) is the property of Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. and its content

may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express

written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Sexual behavior and the non construction of sexual identity Implications for the analysis of men who

Association between cancer screening behavior and family history among japanese women

Associations Between Symptoms of Borderline Personality Disorder, Externalizing Disorders,and Suicid

Forma, Ewa i inni Association between the c 229C T polymorphism of the topoisomerase IIb binding pr

Positive Urgency Predicts Illegal Drug Use and Risky Sexual Behavior

Childhood Maltreatment and Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Associations with Sexual and Relation

The Relationship of ACE to Adult Medical Disease, Psychiatric Disorders, and Sexual Behavior Implic

Posttraumatic Stress Symptomps Mediate the Relation Between Childhood Sexual Abuse and NSSI

Treaty of Peace Between The Allied and AssociatedPowers and Hungary And Protocol and Declaration, Si

MOU between Ralia Odinga and Muslims

Lumiste Betweenness plane geometry and its relationship with convex linear and projective plane geo

A Comparison between Genetic Algorithms and Evolutionary Programming based on Cutting Stock Problem

student sheet activity 3 e28093 object behavior and paths

“Knowing” Lolita Sexual Deviance and Normality in Nabokov’s Lolita

Bechara, Damasio Investment behaviour and the negative side of emotion

What are differences between being a ciwilian and military(1)

MOU between Ralia Odinga and Muslims

Resnick, Mike Between the Sunlight and Thunder

więcej podobnych podstron