Programming Languages

Lecture 5

Types and operations

R. Pełka – Wojskowa Akademia Techniczna

R. Pełka: Programming Languages

2

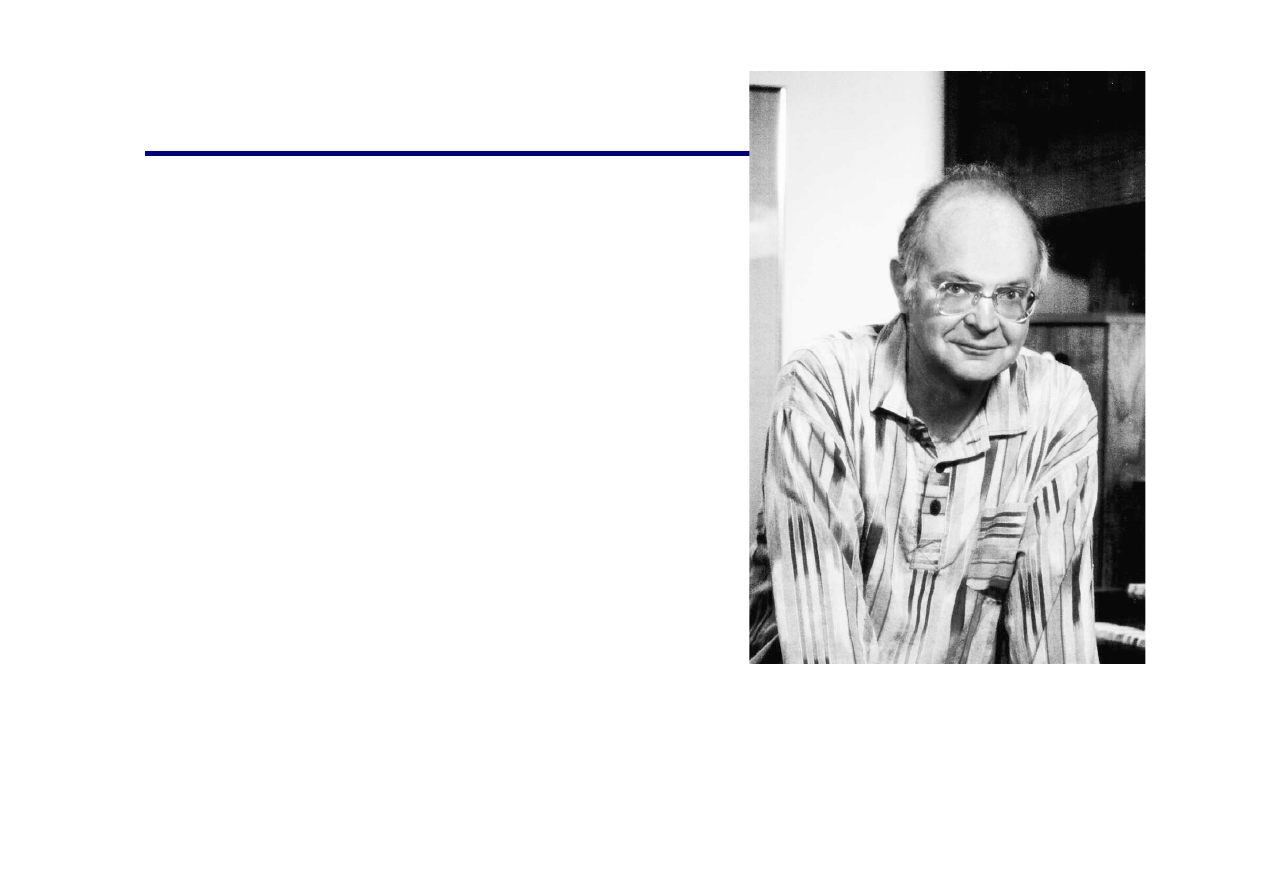

Donald Knuth

(b. 1938)

Scholar, practitioner, artisan

Has written three of seven+ volumes

of The Art of Computer Programming

Began effort in 1962 to survey entire

field, still going

Strives to write beautiful programs

Developed TeX to help typeset his

books, widely used scientific

document processing program

Many, many publications

First was in Mad Magazine

On the Complexity of Songs

Surreal Numbers

R. Pełka: Programming Languages

3

Outline

Java Primitive Types (numerical values)

Type

byte

Type

short

Type

int

Type

long

Type

float

Type

double

Type

char

Type

boolean

Value Ranges and Operators

Variables

Declarations, Assignments, I/O

Constants

Wrapper classes

Type conversion, side-effects

R. Pełka: Programming Languages

4

Primitive types: numerical values

Types for numerical values

Integers (-3, 0, 1, 5500, -29567, …)

Type

byte

Type

short

Type

int

Type

long

Real numbers (0.0, -23.45, 4.67093)

Type

float

Type

double

R. Pełka: Programming Languages

5

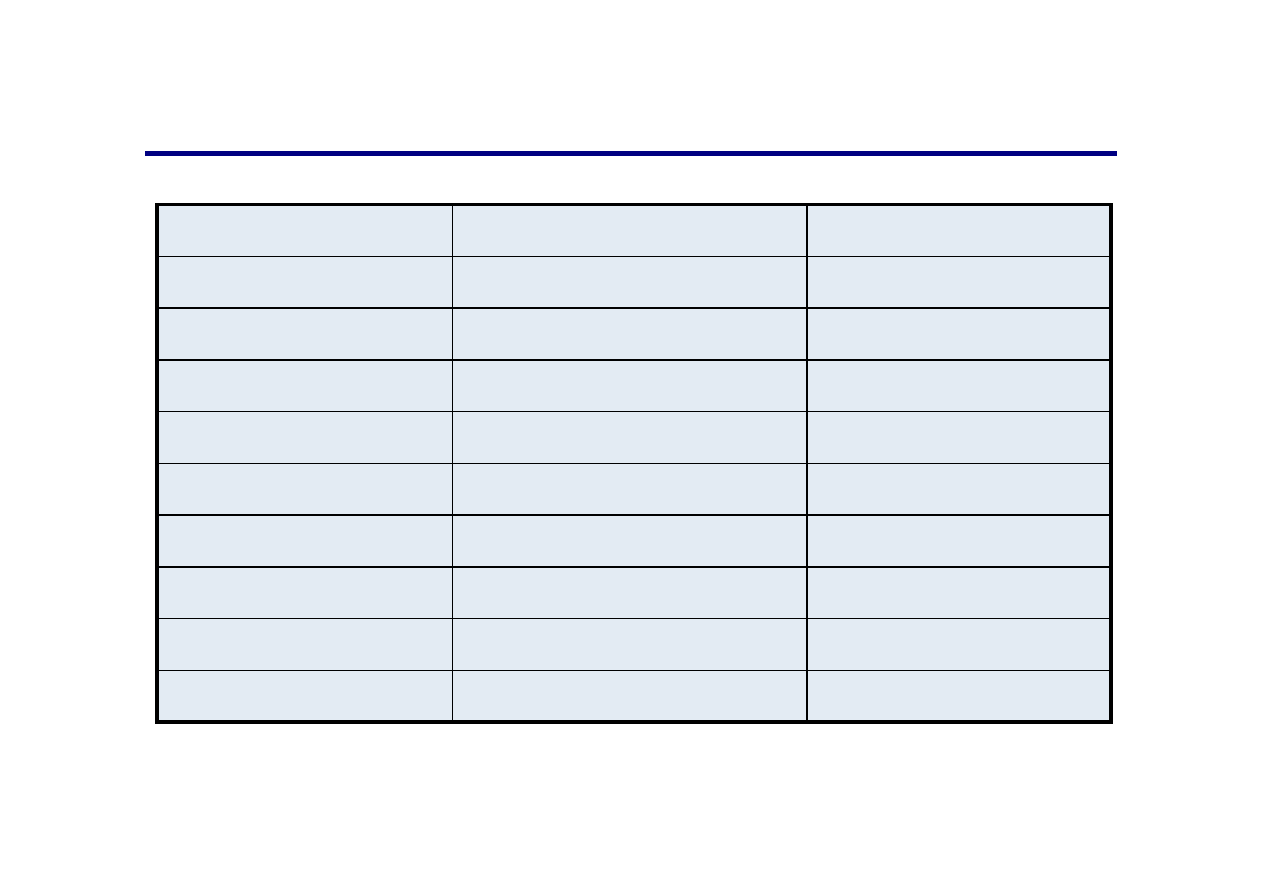

Integers

Different sizes

different sizes (# bits)

allocated in memory for storing the value

different range of possible values

Range

# bits

Type

-9223372036854775808 to 9223372036854775807

64 bits

long

-2147483648 to 2147483647

32 bits

int

-32768 to 32767

16 bits

short

-128 to 127

8 bits

byte

R. Pełka: Programming Languages

6

Real numbers

Range

# bits

Type

+/- 4.94065645841246544 *10

-324

to

+/- 1.79769313486332570*10

+308

64 bits

double

+/- 1.40239846 *10

-45

to +/- 3.40282347 *10

+38

32 bits

float

Different sizes

different sizes (# bits)

Floating point numbers (Float and Double)

Double

higher precision (more decimals)

smaller and bigger values (smaller and bigger power values)

R. Pełka: Programming Languages

7

Arithmetic operators

Basic numerical operators

Remainder (mod)

%

Division

/

Multiplication

*

Subtraction

─

Addition

+

Operators precedence

First priority

* / %

Second priority

+

─

Operators with

higher

priority are applied

first

Operators with

same

priority are applied from

left to right

R. Pełka: Programming Languages

8

Arithmetic operators

Basic numeric operators:

comparisons

attention:

sometimes comparisons may not be 100% safe

test1 = (0.1+0.2==0.3);

produces

false

!!!

Less than or equal to

<=

Greater than or equal to

>=

Inequality

!=

Greater than

>

Less than

<

Equality

==

R. Pełka: Programming Languages

9

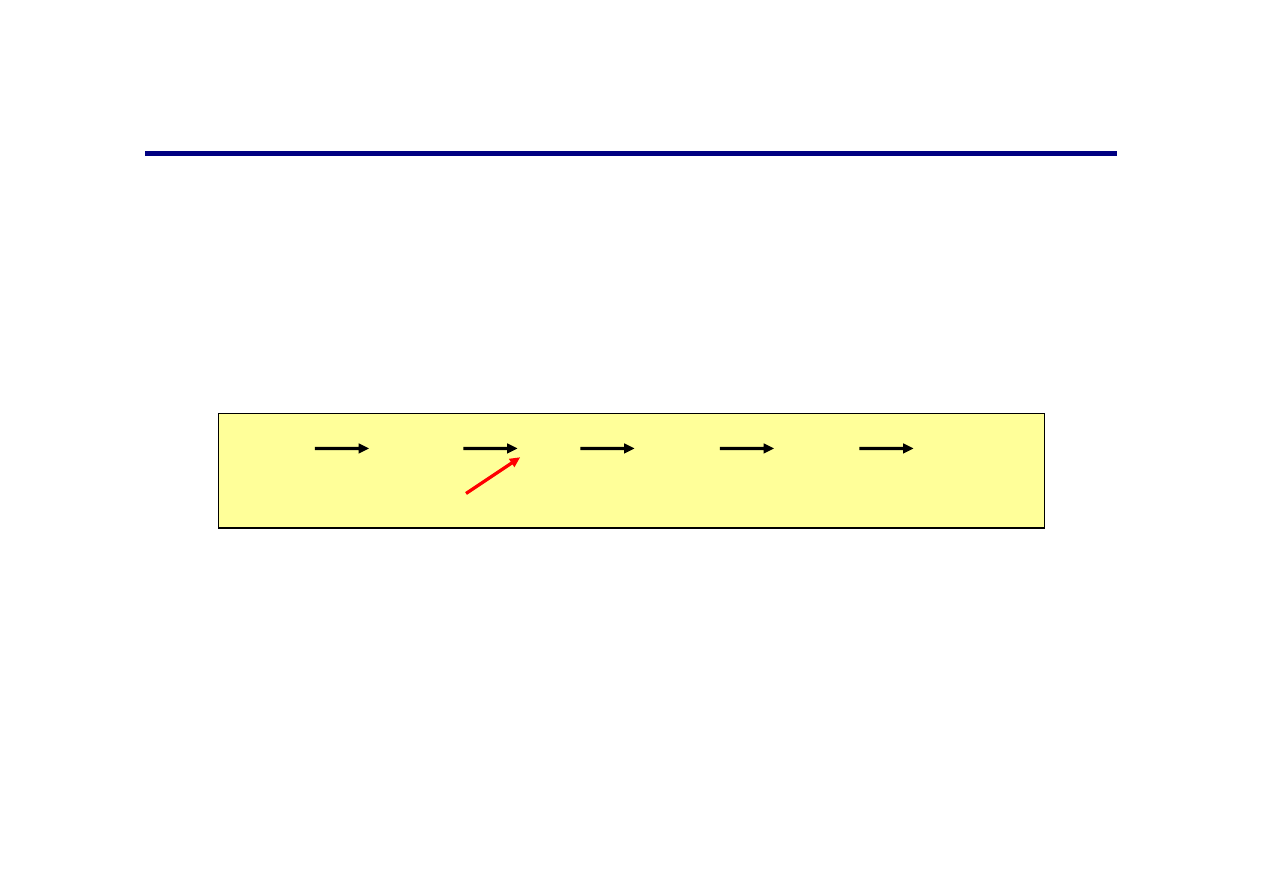

Type conversions

Implicit

conversion

two operands of different numeric type

towards

broadest

numeric type

Occurs during:

Assignments

Arithmetic expression evaluation

String concatenation

Explicit

conversion:

casting

(

<type>

)

<expression>

Example

double f;

int i = 3;

f=(double) i;

byte

short

int

double

float

long

R. Pełka: Programming Languages

10

Variable declaration

Arithmetic Variable Declaration

byte b;

int

i;

short j;

long k;

float

f;

double d;

If no values assigned:

0 by default

variable’s name

variable’s type

R. Pełka: Programming Languages

11

Variable names and declarations

Authorised names (as for String):

sequences of one or more characters.

must begin with a letter or ‘_’

must consist entirely of letters, digits, the underscore character

'_', and the dollar sign character '$'

i i1 i2 anInteger

afloat

examples of bad naming style:

an_Integer, Month_salary, monthsalary

Where to place variable declarations

At the beginning of a method

R. Pełka: Programming Languages

12

Assignment operator

Variable assignments

Numerical variables assignment

<varname> = <arithmetic_expression>;

arithmetic_expression

is one of:

Arithmetic value

Variable of numeric primitive type

Combination of values and/or variables with numeric

operators

Expression evaluates to

same

type as the variable type

Warning:

implicit conversions may change types and

results

R. Pełka: Programming Languages

13

Variable assignments

2

int i = 13 / 5;

200 // implicit conversion (int -> long)

long l = 200;

2.0 // implicit conversion (int -> double)

double f = 13 / 5;

2.6

double f = 13.0 / 5.0;

Evaluated as

Assignment

R. Pełka: Programming Languages

14

Increment and decrement

The increment and decrement operators use only

one operand

The increment operator (

++

) adds one to its operand

The decrement operator (

--

) subtracts one from its

operand

The statement

count++;

is functionally equivalent to

count = count + 1;

R. Pełka: Programming Languages

15

Increment and decrement

The increment and decrement operators can be applied in

postfix

form:

count++

uses old value in the expression,

then increments

or

prefix

form:

++count

increments then uses new value in

the expression

When used as part of a larger expression, the two forms can

have

different

effects

Because of their subtleties, the increment and decrement

operators

should be used with care

x++ + x++

≠

2*(x++)

x++ + x

≠

x + x++

Such effects are known as

side-effects

.

Take care of them!

R. Pełka: Programming Languages

16

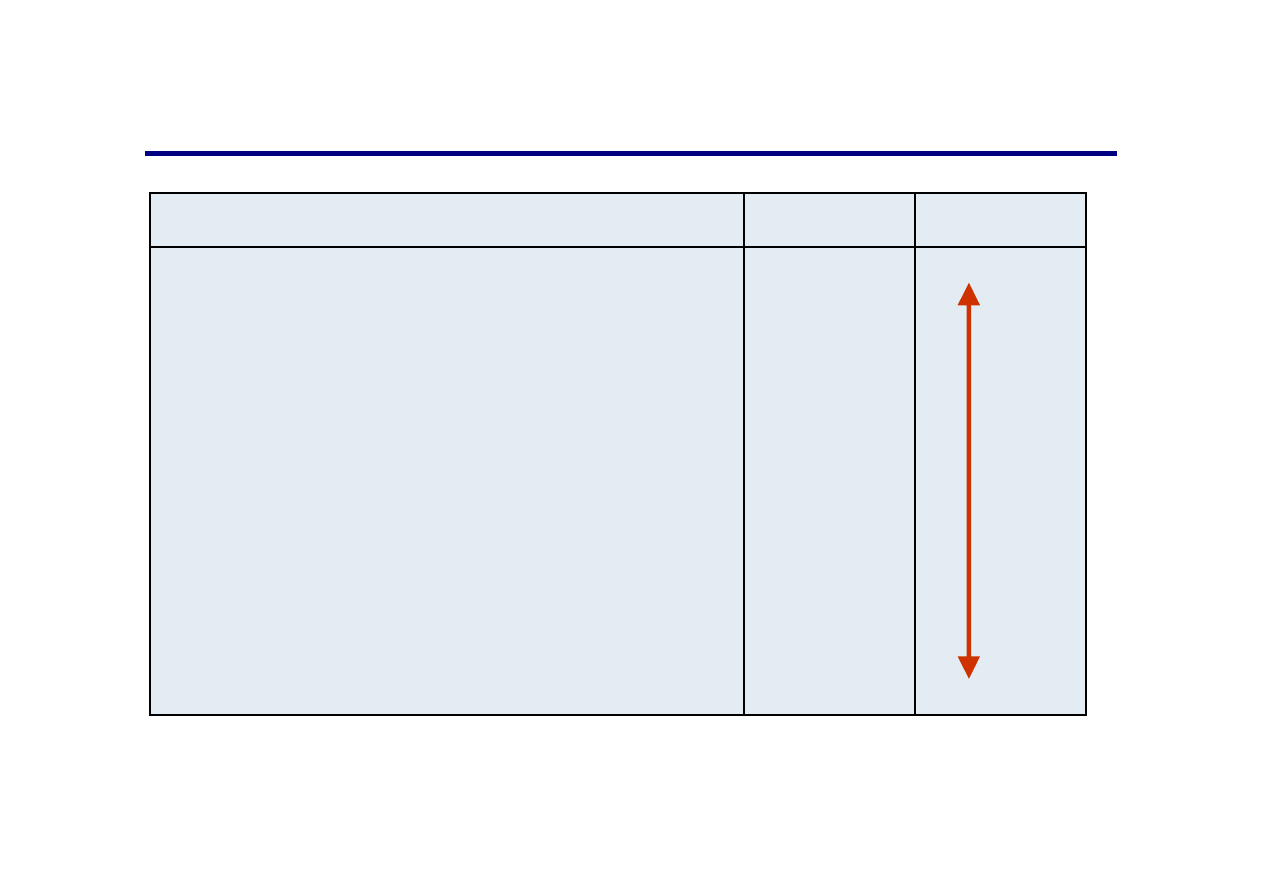

Assignment and ops at once

There are many assignment operators in Java, including

the following:

Operator

Operator

Operator

Operator

+=

-=

*=

/=

%=

Example

Example

Example

Example

x += y

x -= y

x *= y

x /= y

x %= y

Equivalent To

Equivalent To

Equivalent To

Equivalent To

x = x + y

x = x - y

x = x * y

x = x / y

x = x % y

R. Pełka: Programming Languages

17

Numerical values are not Strings

What is the difference between:

int i = 35;

String s = ‘‘35’’;

Assuming the above declarations, are these assignments legal?

i = ‘‘35’’;

i = s;

s = i;

of course, not

String

int

R. Pełka: Programming Languages

18

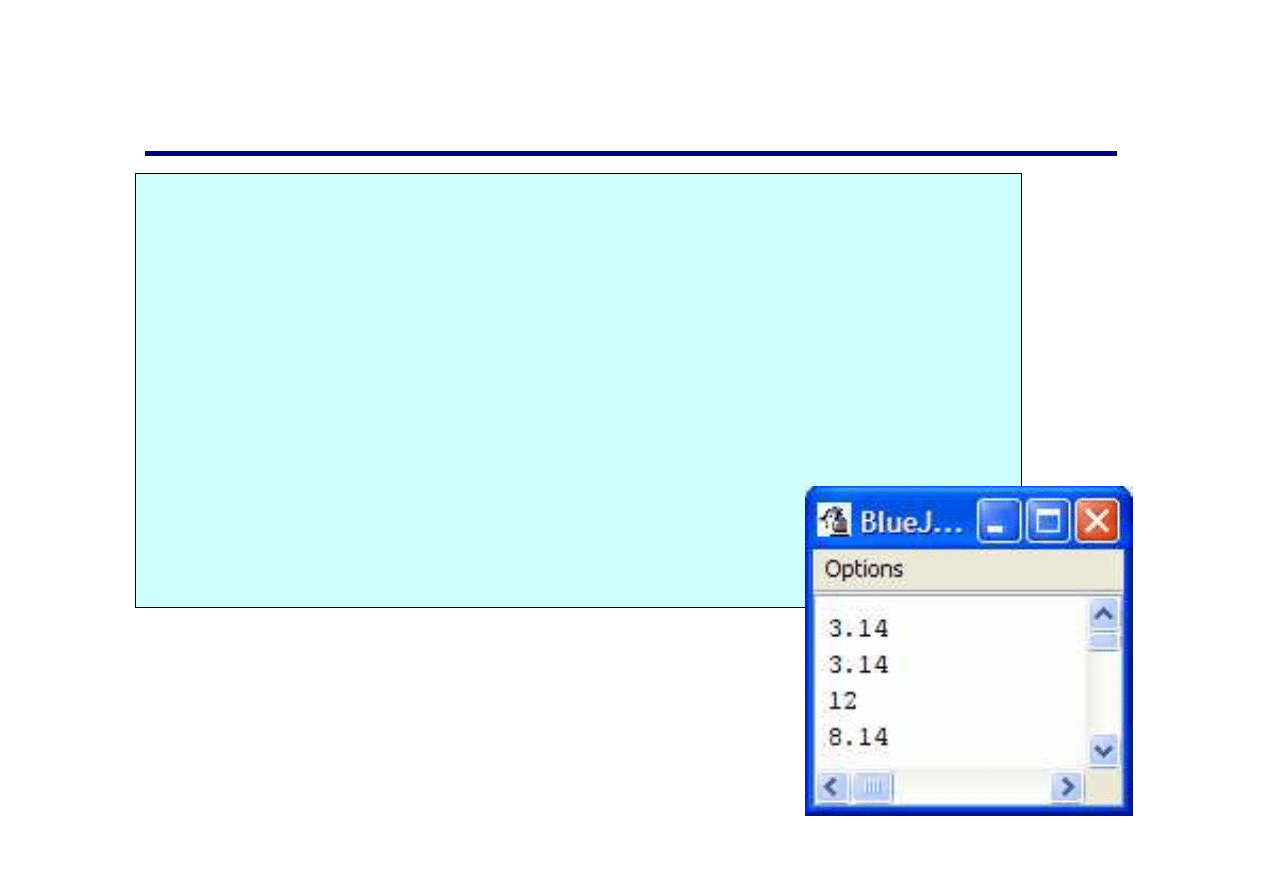

Output in BlueJ

class Test1{

public void printNumericalValues1()

{

double pi = 3.14;

System.out.println(3.14);

System.out.println(pi);

// sums up 5 and 7 then prints 12 as string

System.out.println(5 + 7);

/* converts 5 into double, sums up 5.0 and 3.14

then prints 8.14 as string */

System.out.println(5 + pi);

}

}

R. Pełka: Programming Languages

19

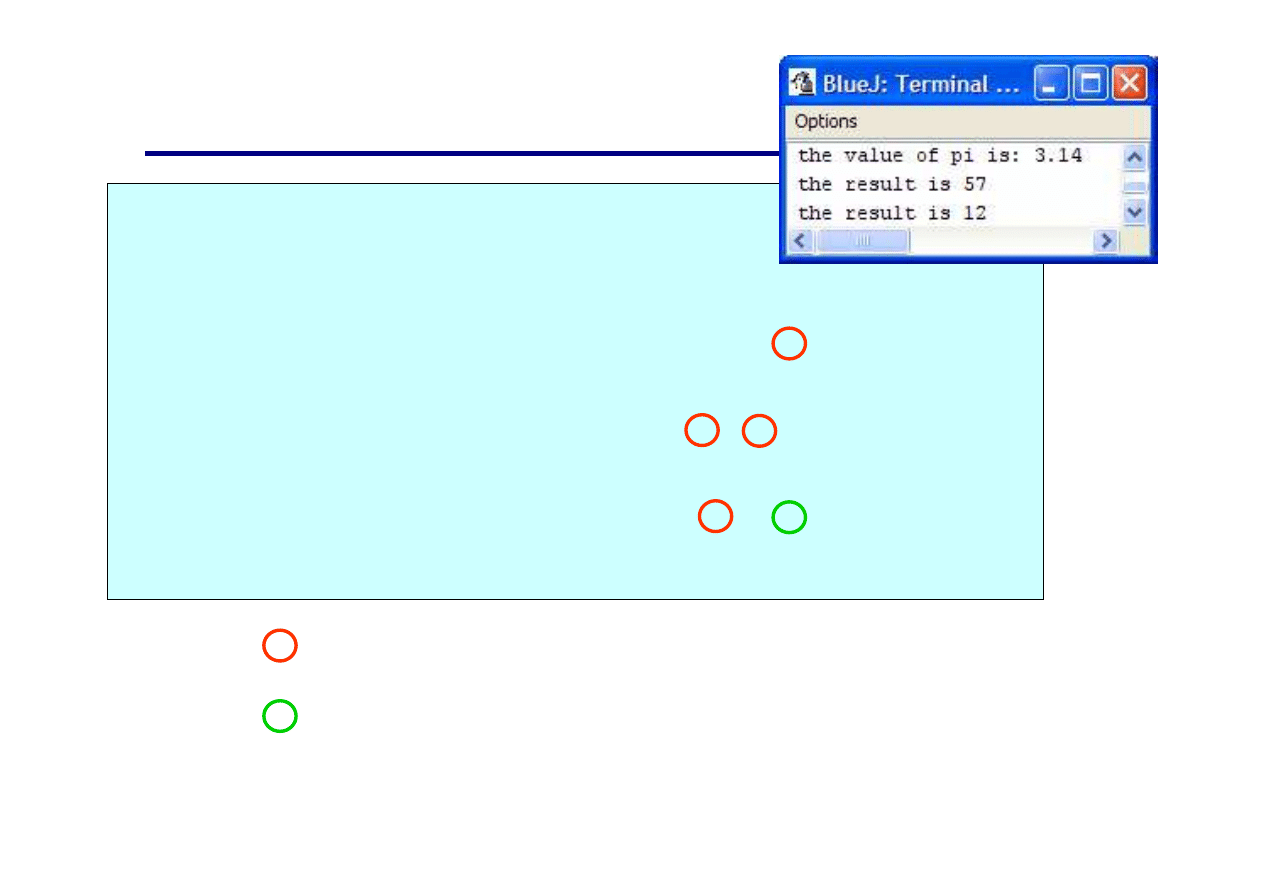

Output in BlueJ

class

Test2{

public static void printNumericalValues2(){

double pi = 3.14;

/* prints numerical value as string and

concatenate with string */

System.out.println("the value of pi is: " + pi);

/* prints numerical value as string and

concatenate with string (the result is 57) */

System.out.println("the result is " + 5 + 7);

/* sums up numerical values, then prints numeric value as

string and concatenate with string (the result is 12)*/

System.out.println ("the result is " + (5 + 7));

}

}

+ as concatenation of strings

+ as arithmetic operator

R. Pełka: Programming Languages

20

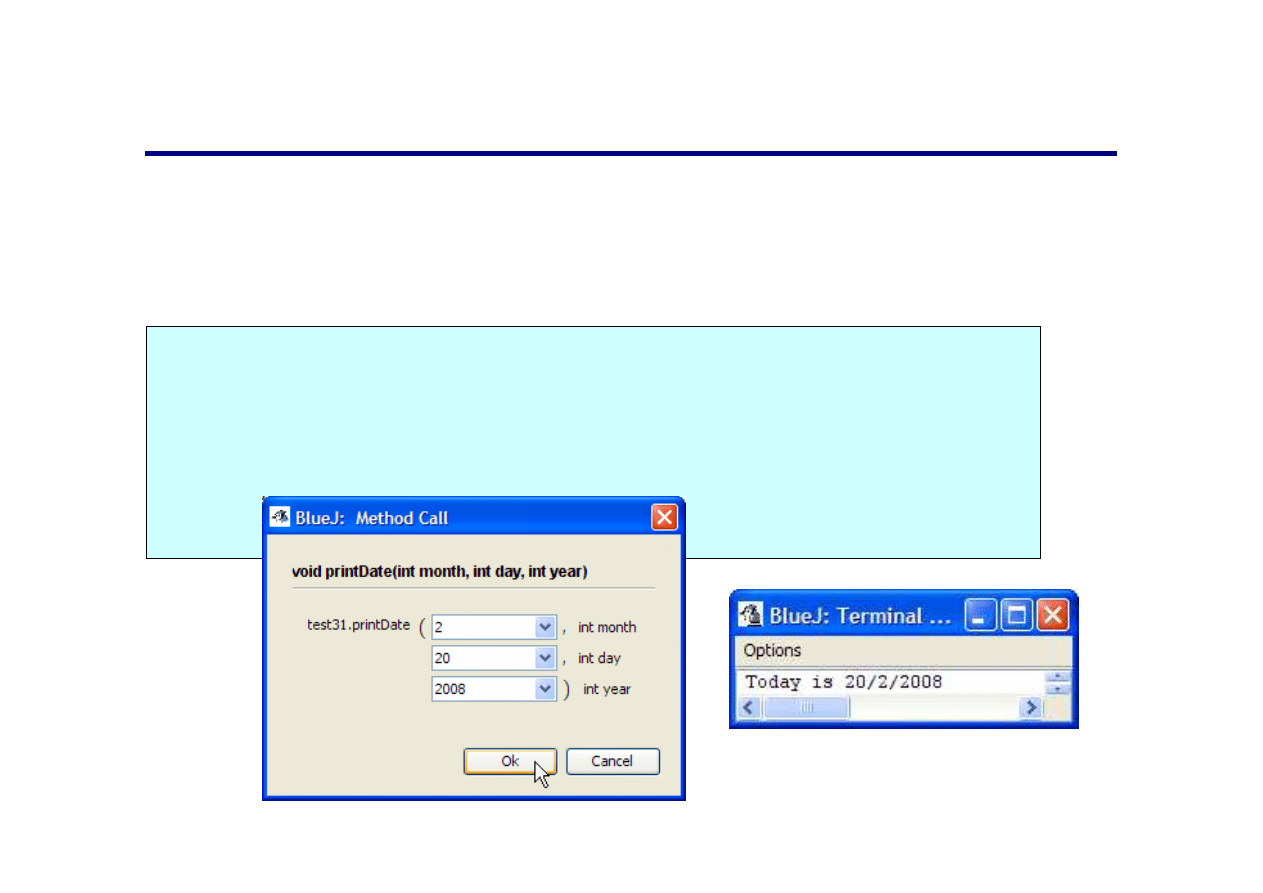

Input in BlueJ

Input of values

direct input without ‘‘ ’’

otherwise it is considered a String

class

Test3{

public void printDate(int month, int day, int year)

{

System.out.println(

"Today is " + day + "/" + month + "/" + year);

}

}

R. Pełka: Programming Languages

21

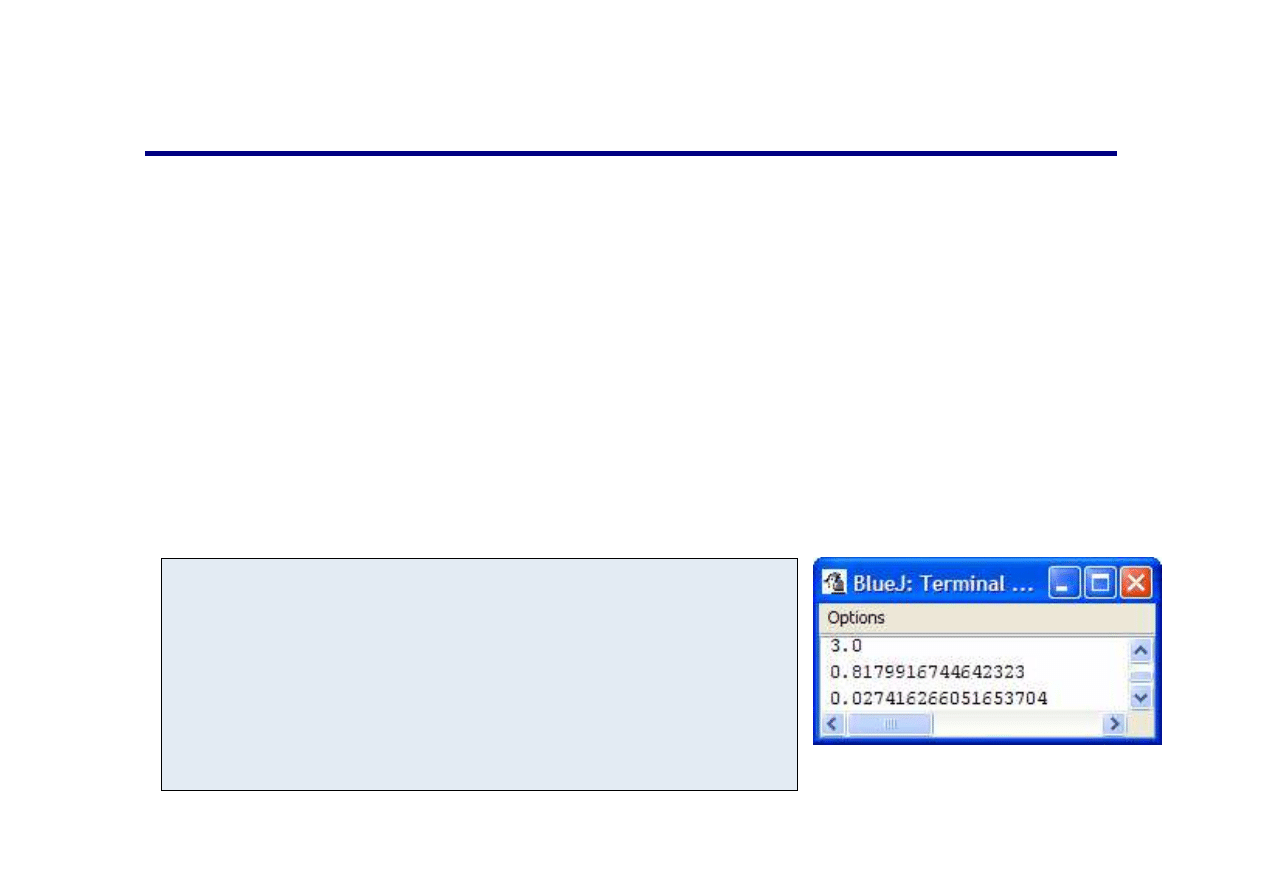

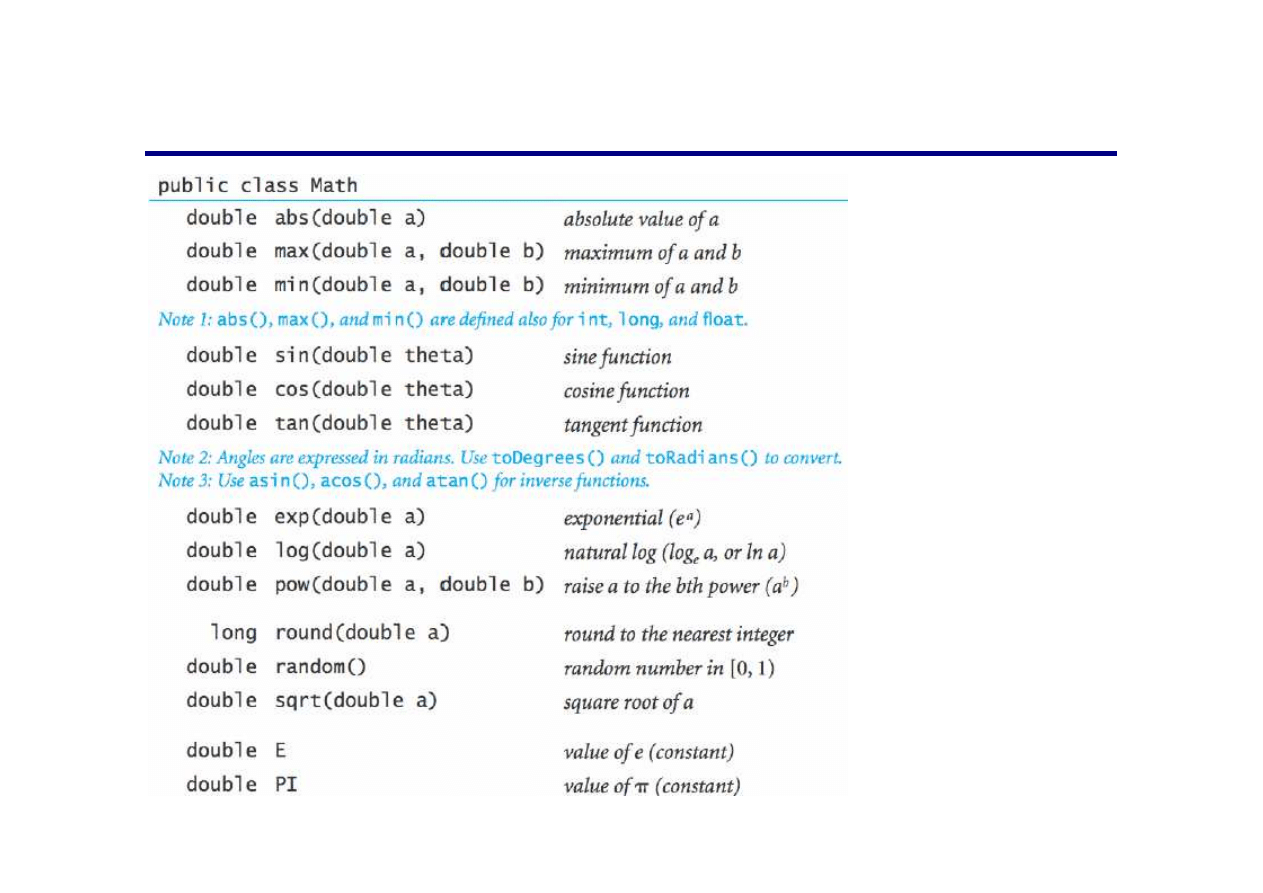

Class Math

(again)

class Math

contains static methods for performing basic numeric operations:

exponential, logarithm – exp(), log()

square root, power – sqrt(), pow()

trigonometric functions – sin(), cos(), tan(), asin() ...

random numbers between 0.0 and 1.0 – random()

rounding functions – floor(), ceil(), round(), rint()

most functions listed above use

double

type

etc. (read API docs for more)

class

Test4{

public static void MathExamples(){

System.out.println(Math.sqrt(9));

System.out.println(Math.random());

System.out.println(Math.random());

}

}

R. Pełka: Programming Languages

22

Class Math

(again)

R. Pełka: Programming Languages

23

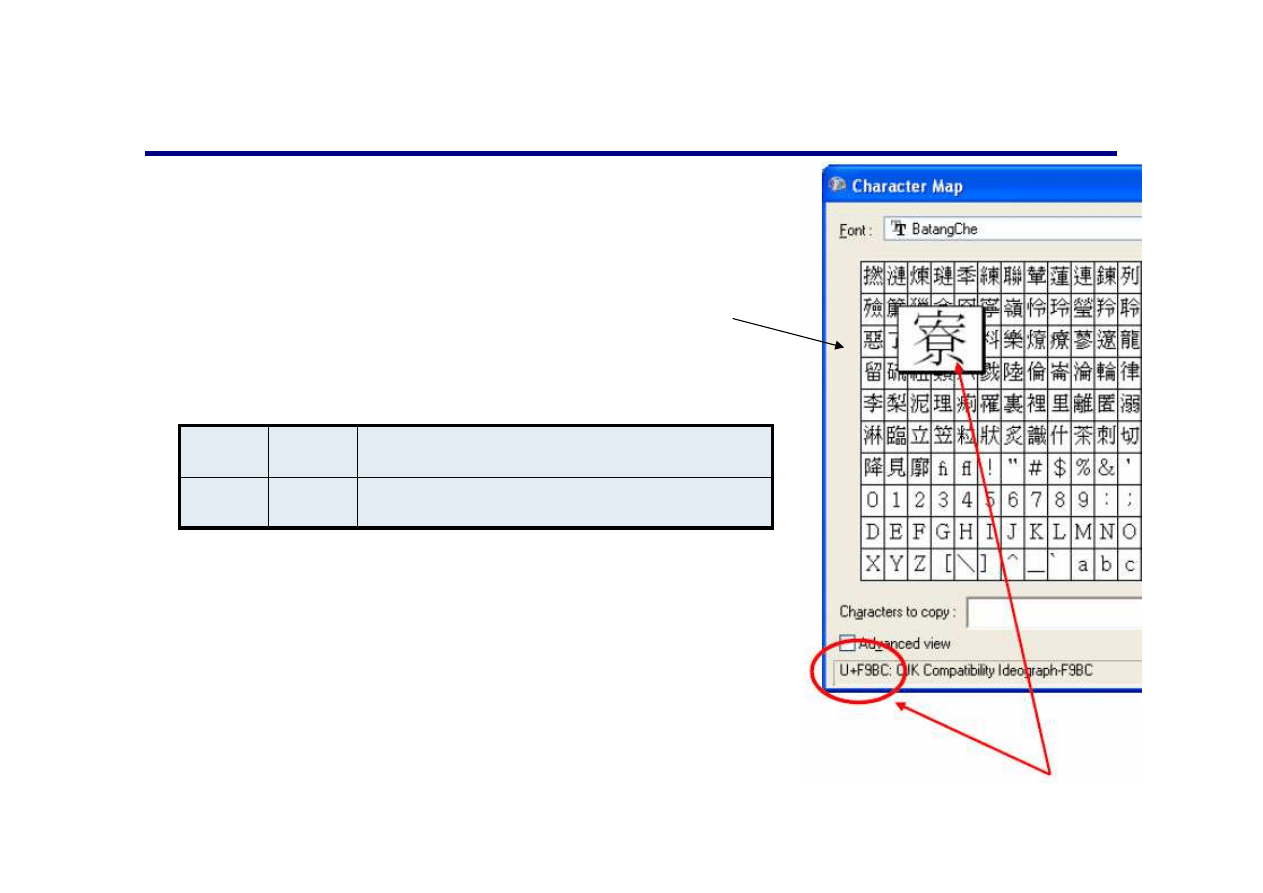

Primitive types: characters

character

‘a’, ‘A’, ‘_’, ‘9’, ‘?’, ‘£’, ‘ ’, ‘\

”

’

Type

char

possible values: all 2

16

(65536)

characters encodable in the Unicode

character set (16-bit values)

considered numeric values

Java supports the UNICODE but many

software tools like editors and operating

systems do not support UNICODE

When c is the char, then c++ is the next

character and c-- is the previous one

Non printable chars eg.: \n, \t, \r

Values

# bits

Type

0x0 to 0xffff (hexadecimal notation)

16

char

char code \uF9BC

R. Pełka: Programming Languages

24

Arithmetic operators for

char

Same

as numeric operators

What happens then?

the binary content is considered in the expression

binary promotion to type

int

Numeric Types conversion

Occurs during:

assignments

arithmetic expression evaluation

string concatenation with other data types

byte

short

int

double

float

long

char

R. Pełka: Programming Languages

25

Type conversion, names, declarations

Explicit

conversion:

(

<type>

)

<expression>

Examples

char a = ‘Z’;

char b = ‘@’;

int i = a; // numeric value 98

i=(int) b; // numeric value 64

a = (char) 80; // character ‘P’

Naming rules same as for other primitive types

a b a1 aChar a_char

Declarations

char a, b, my_char;

if no initial value assigned 0000 (hex) by default

R. Pełka: Programming Languages

26

Type char – arithmetic operators

50

0011 0010 (= 50

10

)

(int) ‘2’

b (0110 0010)

0110 0001 + 0000 0001

(char) (‘a’ + 1)

a

0110 0001

‘a’

4 (the character)

0011 0010 + 0000 0010

(char) (‘2’ + 2)

2 (the numeric value)

0000 0010 (= 2

10

)

2

52 (the numeric value)

0011 0010 + 0000 0010

‘2’ + 2

2 (the character)

0011 0010

‘2’

0110 0001 + 0000 0001

0110 0001 (= 97

10

)

Evaluated as

98

97

Result

‘a’ + 1

(int) ‘a’

Expression

R. Pełka: Programming Languages

27

char

– comparisons

Same as for other primitive types

Less than or equal to

<=

Greater than or equal to

>=

Inequality

!=

Greater than

>

Less than

<

Equality

==

What is the difference between:

int i = 2;

// numeric value 2

char a = ‘2’;

// equivalent to numeric value 50

String s = ‘‘2’’; // a Java (String) Object

R. Pełka: Programming Languages

28

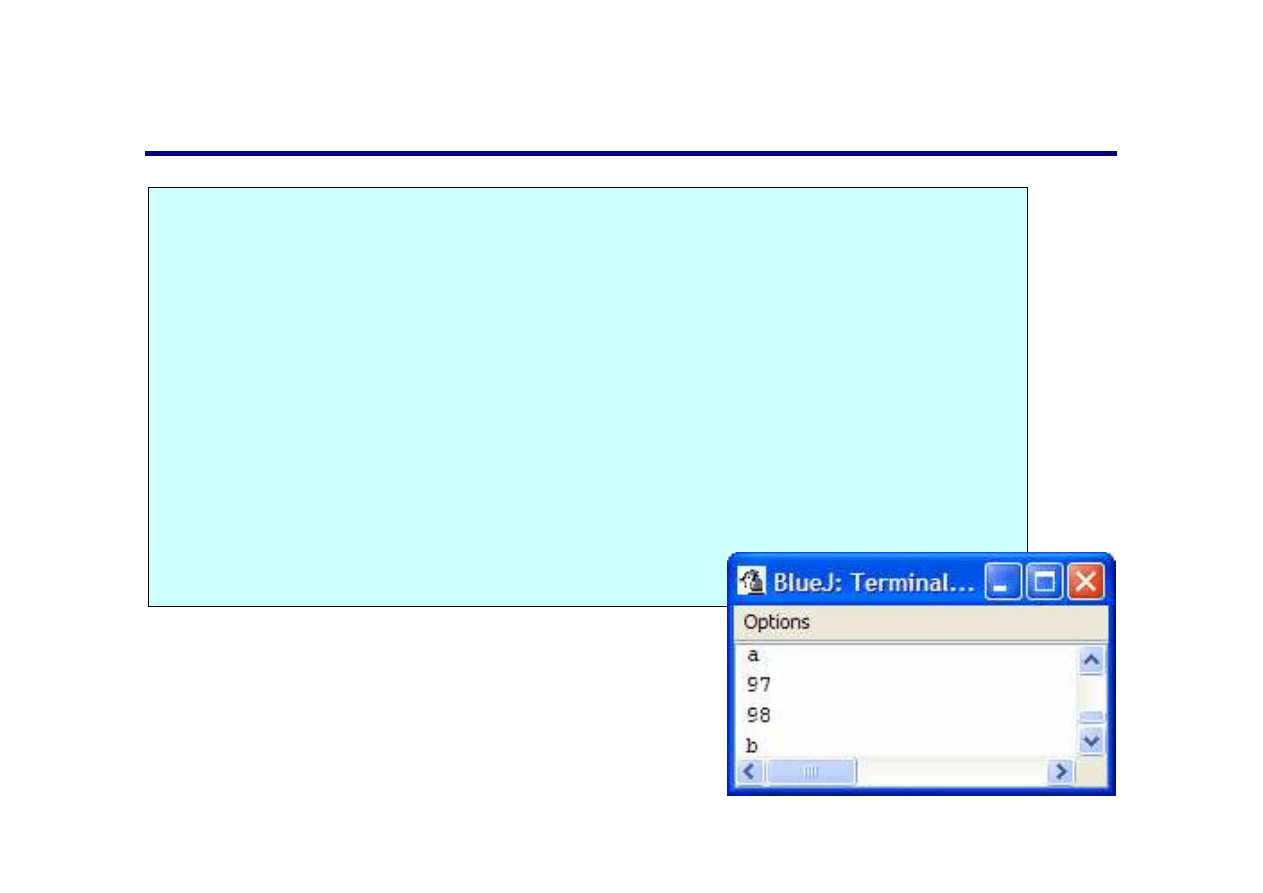

Output in BlueJ

class Test5{

public void printCharValues1()

{

char a_char = 'a';

// prints the character value stored in a_char: ‘a’

System.out.println(a_char);

// type conversion, prints 97

System.out.println((int) a_char);

// sums up 97 + 1, result: 98

System.out.println(a_char + 1);

// sums up 97 + 1, and then converts to char: ‘b’

System.out.println((char) (a_char +1));

}

}

R. Pełka: Programming Languages

29

Primitive types:

boolean

boolean primitive type, names as for other

primitive types

type

boolean

values:

true false

type conversion

no type conversion!

relational operators

apply on operands of

numeric

primitive data types

return

boolean

value

2 < 4 , 4 <= 0 , 3.14 > 9

a greater than or equal to b?

a >= b

a greater than b?

a > b

a less than or equal than b?

a <= b

a less than b?

a < b

George Boole

the English mathematician (1815-1864)

R. Pełka: Programming Languages

30

Operators

Equality Operators

Apply on

operands of primitive data type

Return

boolean

value

(2 == 4) , (‘@’ != 6) , (true == false)

Boolean Logical Operators

Apply on

boolean expressions

Return

boolean

value

(2 > 4) && (5 < 0),

!true || true

Inequality

Equality

Are a and b not equal? (different primitive value?)

a != b

Are a and b equal? (same primitive value?)

a == b

OR

AND

true

if either or both x, y are true, otherwise

false

x || y

true

if both x and y are true, false otherwise

false

x && y

R. Pełka: Programming Languages

31

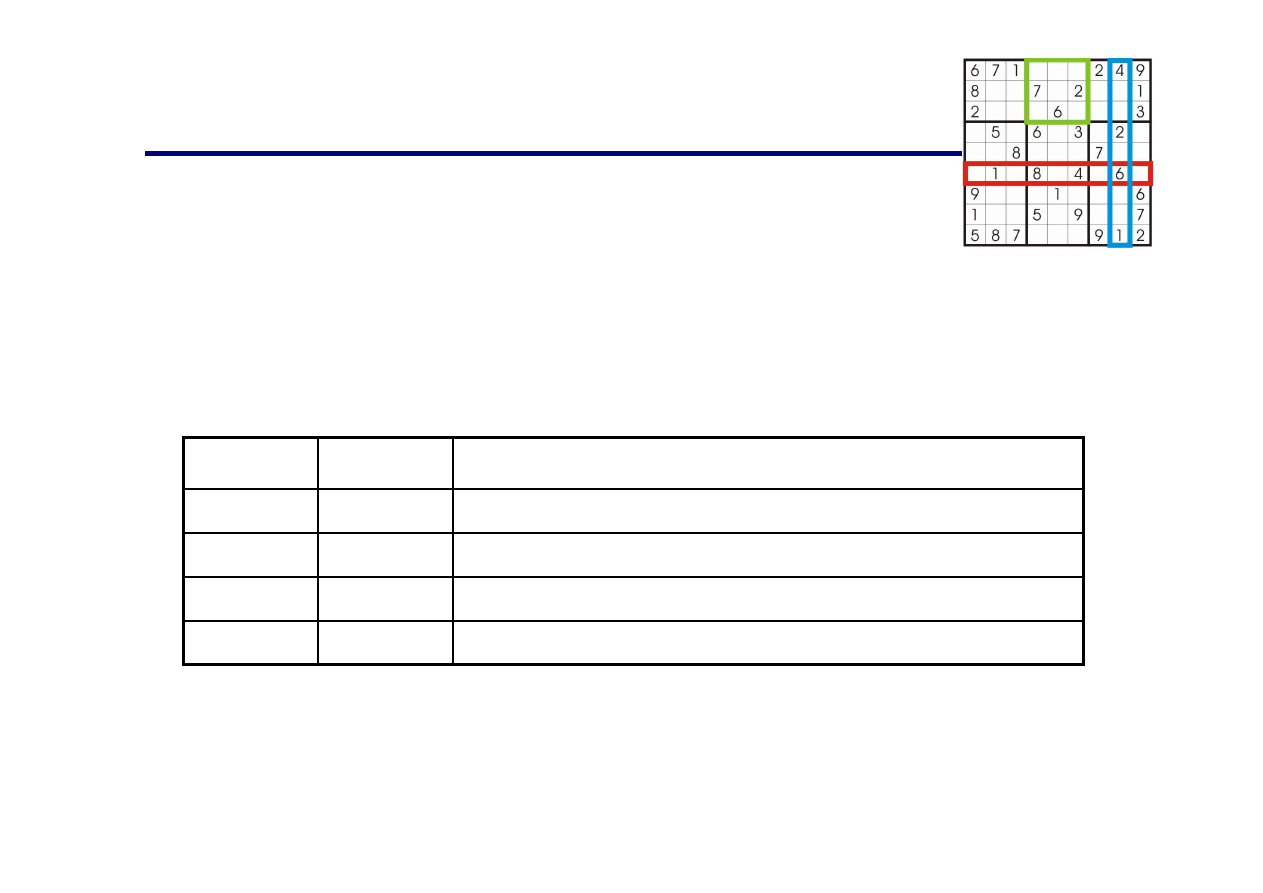

Operator precedence

Operator precedence

not

!

relational operators

< <= > >=

equality operators

== !=

logical and

&&

logical or

||

‘@’ != 6

(4 == 2) == true

false | false & true

!false || (2 >= 8)

(4 == 2) && (1 < 4)

Expression

false

((4 == 2) == true)

false

(4 == 2) && (1 < 4)

true

(‘@’ != 6 )

false

true

Result

(false | (false & true))

(!false) || (2 >= 8)

Evaluated as

Examples

boolean b = (2 == 4);

boolean c = (b & true);

R. Pełka: Programming Languages

32

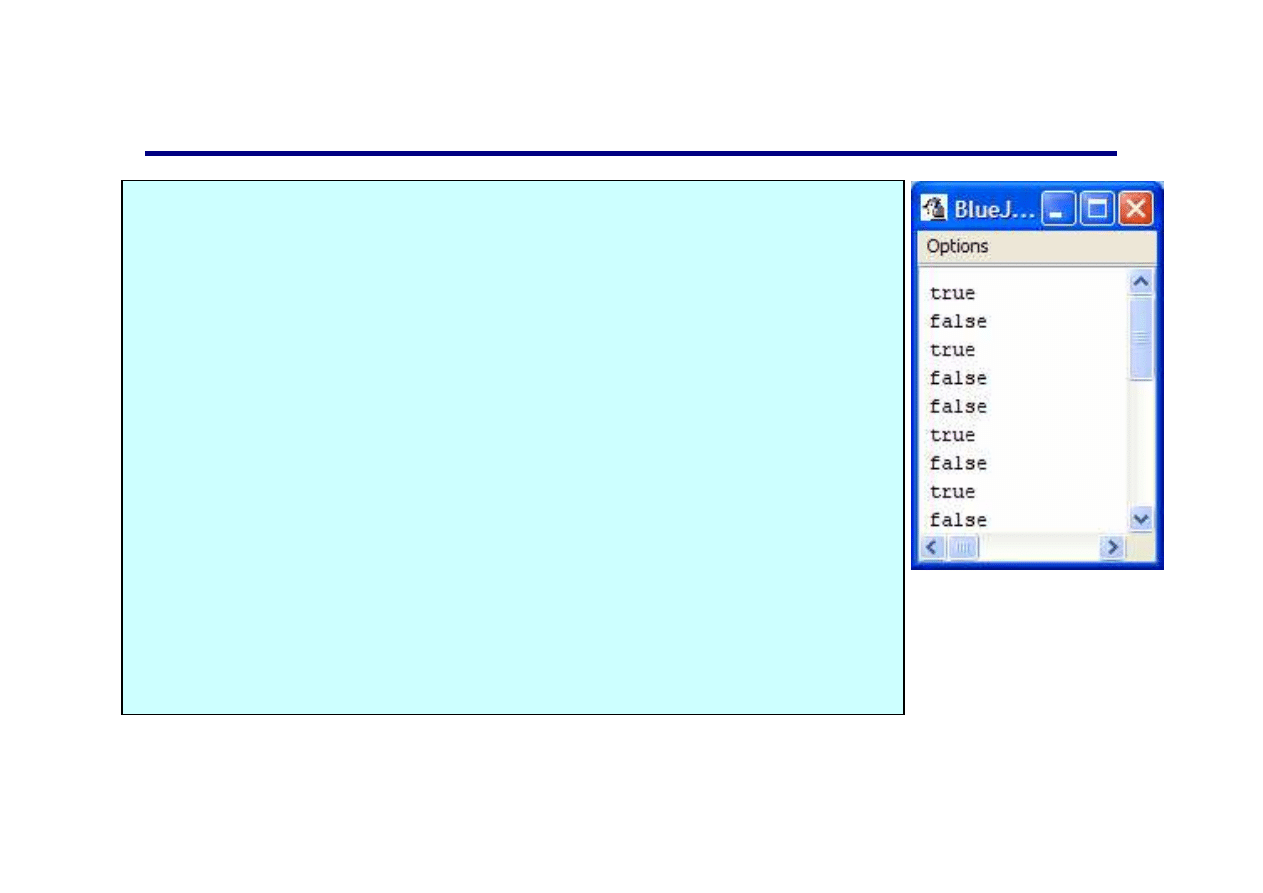

Output in BlueJ

class Test6{

public void printTest(){

boolean b = (4 == 2) && (1 < 4);

// operate on constants

System.out.println(true);

System.out.println((4 == 2) && (1 < 4));

System.out.println(!false || (2 >= 8));

System.out.println(false || false && true);

System.out.println((4 == 2) == true);

System.out.println('@' != 6);

// operate on variables

System.out.println(b);

System.out.println(!b || (2 >= 8));

System.out.println(b || b && true);

}

}

R. Pełka: Programming Languages

33

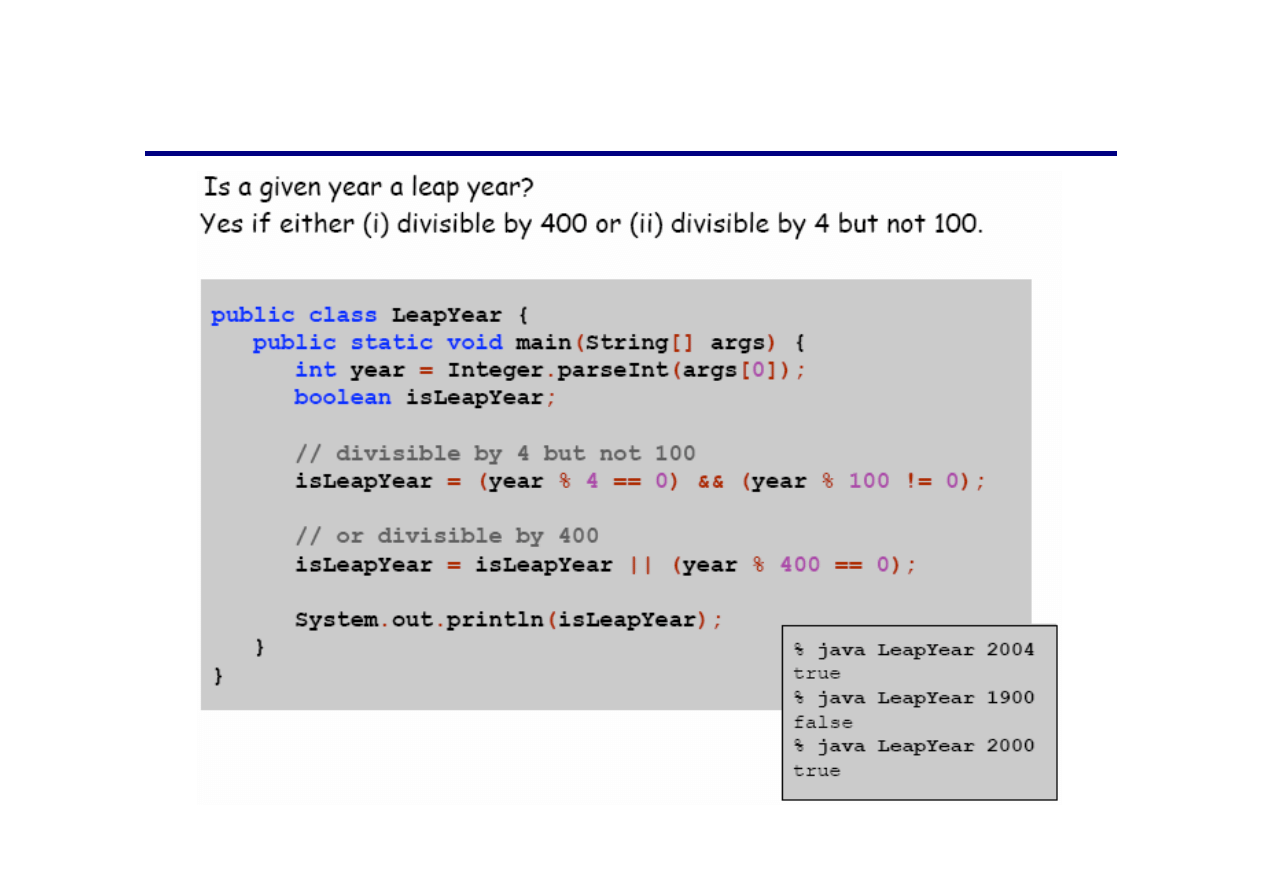

Boolean expressions – example

R. Pełka: Programming Languages

34

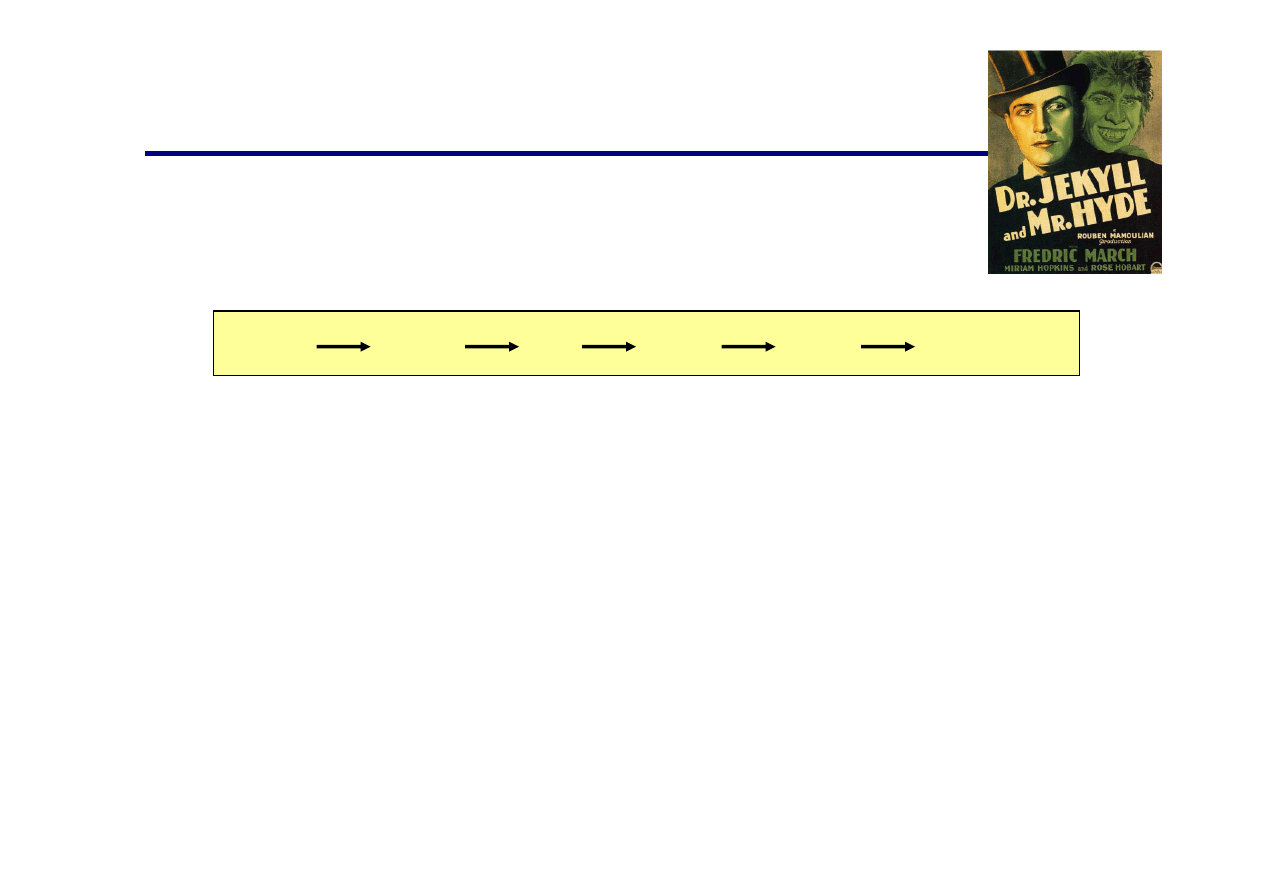

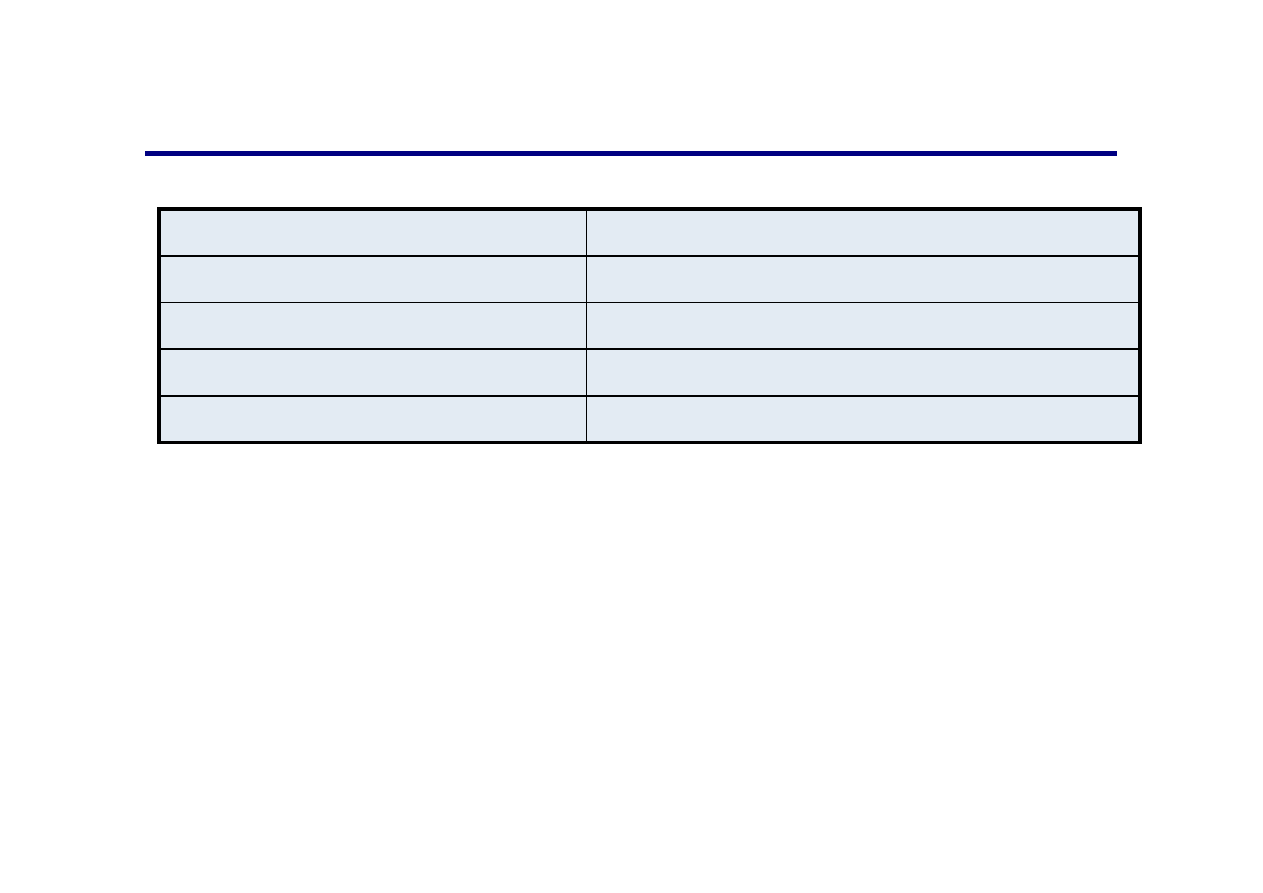

Java operators – summary

Arithmetic Op. :

Arithmetic Op. :

+ -

* / %

Relational Op. :

Relational Op. :

> >= < <= == !=

Logical Op. :

Logical Op. :

&& || !

Inc/Dec Op. :

Inc/Dec Op. :

++ --

Bit Op. :

Bit Op. :

& | ^ ~ << >> >>>

Operators

of Java

Conditional Op. :

Conditional Op. :

?:

Assign Op. :

Assign Op. :

= += -= *= /= %= &= ^= |= >>= <<= >>>=

Casting Op. :

Casting Op. :

(Data Type)

Array Op. :

Array Op. :

[]

Method Op. :

Method Op. :

() .

instanceof

instanceof

Op. :

Op. :

instanceof

R. Pełka: Programming Languages

35

Operators precedence

Operator Association Precedence

() [] .

! ~ ++ -- + -

(Data Type)

* / %

+ -

<< >> >>>

(Shift left, right, right unsigned)

< <= > >= instance

== !=

&

^

|

&&

||

? :

= += -= *= /= %= &= ^= |= <<= >>= >>>=

Left Assoc. (High)

Left Assoc.

Left Assoc.

Left Assoc.

Left Assoc.

Left Assoc.

Left Assoc.

Left Assoc.

Left Assoc.

Left Assoc.

Left Assoc.

Left Assoc.

Left Assoc.

Left Assoc. (Low)

R. Pełka: Programming Languages

36

Wrapper classes

Sometimes it is necessary for a

primitive

type

value to be an

Object

, rather than

just a primitive type.

Some data structures

only store Objects

.

Some Java methods

only work on Objects

.

Wrapper classes

also contain some

useful constants and a few handy

methods.

Body wrapper

from Egypt

R. Pełka: Programming Languages

37

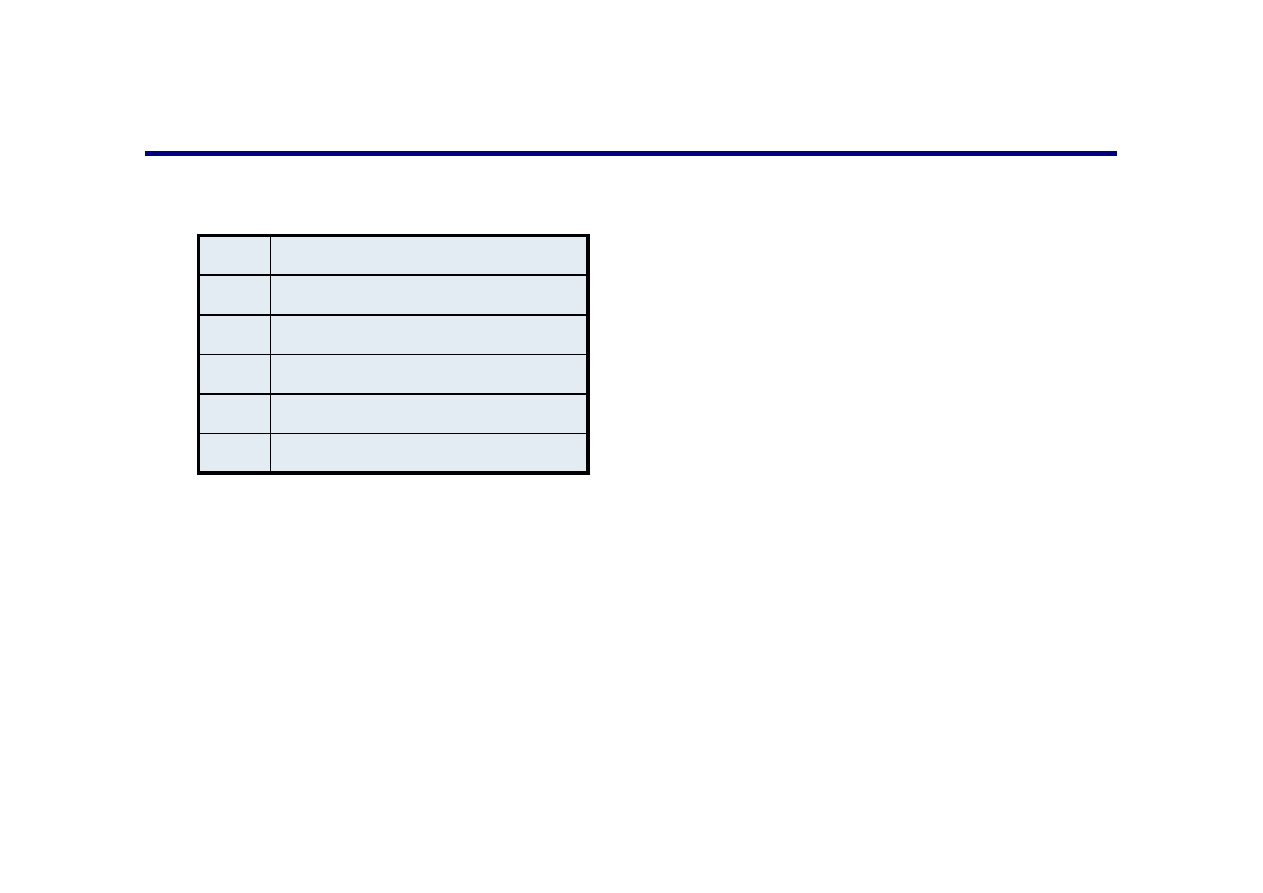

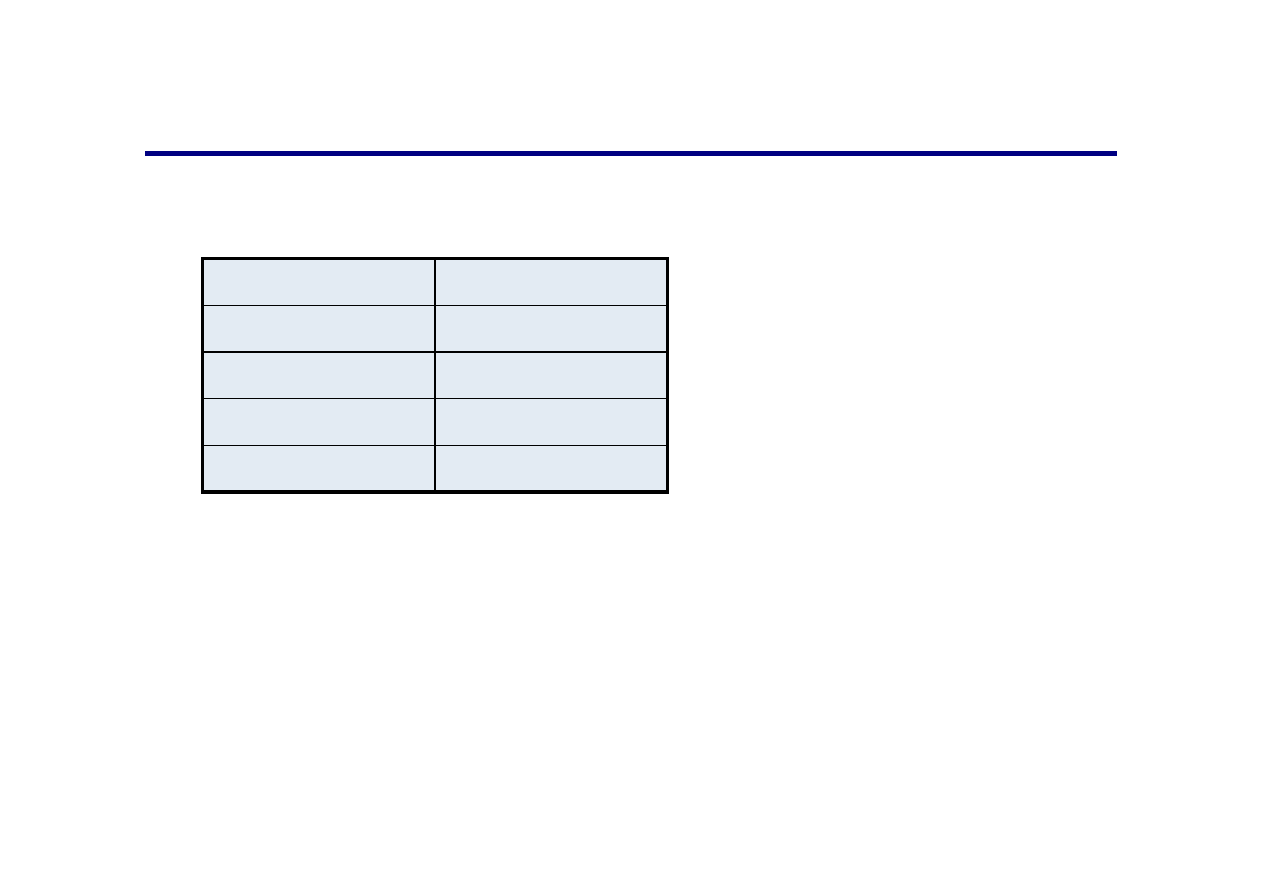

Wrapper classes

Each

primitive type

has an associated

wrapper class

:

Each wrapper class

Object

can hold the value that would normally

be contained in the primitive type variable, but now has a number of

useful static methods.

Double

double

Float

float

Long

long

Integer

int

Character

char

R. Pełka: Programming Languages

38

Wrapper classes

Integer number = new Integer(46);

//”Wrapping”

Integer num = new Integer(“908”);

Integer.MAX_VALUE

// gives maximum integer

Integer.MIN_VALUE

// gives minimum integer

Integer.parseInt(“453”)

// returns 453

Integer.toString(653)

// returns “653”

number.equals(num)

// returns false

int aNumber = number.intValue();

// aNumber is 46

R. Pełka: Programming Languages

39

Wrapper classes

The

Double

wrapper class has equivalent methods:

Double.MAX_VALUE

// gives maximum double value

Double.MIN_VALUE

// gives minimum double value

Double.parseDouble(“0.45E-3”)

// returns 0.45E-3

parseDouble

is only available in Java 2 and newer

versions.

See the Java documentation for more on Wrapper

classes.

R. Pełka: Programming Languages

40

Constants

Things that do not vary

unlike variables

will never change

Syntax:

final

typeName variableName = value;

Example

final

int DELAY_MS = 120;

Constant names in all upper case

Java convention, not compiler/syntax requirement

Some predefined constants available:

E, PI

(java.lang.Math)

R. Pełka: Programming Languages

41

Programming with constants

public static void main (String[] args)

{

double lightYears, milesAway;

final int LIGHTSPEED = 186000;

final int SECONDS_PER_YEAR = 60*60*24*365;

lightYears = 4.35; // to Alpha Centauri

milesAway = lightYears

* LIGHTSPEED * SECONDS_PER_YEAR

;

System.out.println("lightYears: " + lightYears + " miles " + milesAway);

lightYears = 68; // to Aldebaran

milesAway = lightYears

* LIGHTSPEED * SECONDS_PER_YEAR

;

System.out.println("lightYears: " + lightYears + " miles " + milesAway);

}

avoid

magic numbers

in your programs,

use constants

instead

these two constants should also be defined as constants

R. Pełka: Programming Languages

42

Class constants

public class X{

//becomes a class constant

public

static

final

int

ACONSTANT=100

;

}

public class Y{

private int var;

void method()

{

var=

X.ACONSTANT

*2;

}

}

Similarly like variables and

methods, you can use constants

defined in other classes

they must be defined as

public

if definition is in an upperclass, the

name of class before constant

reference can be omitted

R. Pełka: Programming Languages

43

Summary

Java Primitive Types (numerical values)

Type

byte

Type

short

Type

int

Type

long

Type

float

Type

double

Type

char

Type

boolean

Value Ranges and Operators

Variables

Declarations, Assignments, I/O

Constants

Wrapper classes

Type conversion, side-effects

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Lecture5 Monstrosity and cont visual arts

Different types and styles of wrestling

Heathkit AA 151 Stereo Amplifier Assembly and Operation manual

#1038 Types and Characteristics of Apartments

forrester cloud email infrastructure and operations analysis

lecture 3 KM and culture 2008

M Euwe Course of chess lectures, Strategy and tactic (RUS, 1936) 2(1)

Lecture 1 Theory and methodology

więcej podobnych podstron