Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1719796

1

Online Investors: What They Want, What They Do, And How Their

Portfolios Perform

1

Arvid Hoffmann

*

Maastricht University and Network for Studies on Pensions, Aging and Retirement (Netspar)

Hersh Shefrin

Santa Clara University

Abstract: For 5,500 individual online investors we match survey records with recent trading data to

gain a better understanding of the relationships among investors’ decisions, the processes leading to

these decisions, and resulting performance. We investigate what online investors want, in terms of

their stated objectives for investing, what they do, in terms of the broad investing strategies they

employ, and how their portfolios perform in terms of return, risk, and factor exposure. In particular,

we analyze how systematic differences in investors’ traits interact with their objectives and strategies.

Our results provide insights into the impact on investors’ portfolios stemming from overconfidence,

perceived competence, gambling and speculation, and risk appetite. These four variables have

received emphasis in the recent literature in which survey and transaction data are matched. We find

that investor traits such as experience, risk appetite, and ambition, objectives related to speculation,

and strategies relying on intuition and/or technical analysis are critical determinants of turnover. We

find that individual investor return performance is adversely impacted by demographic characteristics

such as length of online trading experience, and by strategies featuring the use of technical analysis

and/or advice from brokers. Notably, we find little if no evidence that investor returns are positively

correlated with risk, if anything the reverse.

JEL Classification: G11, G24

Keywords: Individual Investors, Behavioral Biases, Investment Decisions, Investor Performance.

*

Corresponding author: Arvid O. I. Hoffmann, Maastricht University, School of Business and Economics,

Department of Finance, P.O. Box 616, 6200 MD, The Netherlands. Tel.: +31 43 38 84 602. E-mail:

a.hoffmann@maastrichtuniversity.nl.

1

This research would not have been possible without the collaboration of a large online broker. The authors

thank this broker and all its employees who helped us. For their comments on previous drafts of this paper, the

authors thank Jeroen Derwall, Ingolf Dittmann, Marty Leibowitz, Andrew Lo, Harry Markowitz, Carrie Pan,

Bill Sharpe, Yossi Spiegel, Meir Statman and seminar participants at INSEAD (2010), the IMCA Advanced

Wealth Management Conference (2010), and the JOIM Spring Conference on Modern Portfolio Theory: The

Evolution and Future (2011). Special thanks to our JOIM discussant Jim Peterson, chief investment officer for

Charles Schwab Investment Advisory and portfolio manager for Schwab Managed Portfolios, who indicated

that American online investors share the same characteristics as those reported for Dutch investors in our paper.

The title of our paper is inspired by Meir Statman’s book “What Investors Really Want.” Any errors are, of

course, our own.

Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1719796

2

1. Introduction

Our paper investigates what online investors want, in terms of their stated objectives for investing,

what they do, in terms of the investing strategies they employ, and how their portfolios perform in

terms of return, risk, and factor exposure. The main contribution of this paper is that it uses matched

survey data and transaction data to characterize the variation in online investors' primary investment

objectives, their broad strategies, and their key psychological traits, along with an analysis of how

these variables influence the risk-return and turnover profiles of their portfolios.

This paper broadens and extends the recent literature that matches survey data to trading data.

This literature emphasizes the important role that psychological factors play in the investment

decision process. These factors broadly pertain to the “better than average” notion of overconfidence

(Dorn and Huberman 2005; Glaser and Weber 2007a; Glaser and Weber 2007b), self-perceived

competence (Graham, Harvey, and Huang 2009), entertainment and gambling/sensation seeking

(Dorn and Sengmueller 2009), and risk appetite (Dorn and Huberman 2005).

2

Dorn and Huberman (2005) find that investors who think they are knowledgeable about financial

securities hold better diversified portfolios, while those who rate themselves as above average in

terms of knowledge churn their portfolios more (see also Glaser and Weber 2007a). In a related vein,

Glaser and Weber (2007b) find a tendency among individual investors to overestimate their relative

position in terms of return percentile, indicating a better than average effect. However, they do not

find evidence for a “learning to be overconfident” effect (Gervais and Odean 2001) as actual (past)

returns are not correlated with the (current) degree of overconfidence of these investors. Graham et al.

(2009) find that investors who feel competent trade more and have more internationally diversified

portfolios. In addition, males and investors with larger portfolios or more education are more likely to

perceive themselves as competent. Dorn and Sengmueller (2009) find that investors who report

enjoying investing or gambling turn over their portfolio at twice the rate of their peers. Finally, Dorn

and Huberman (2005) find that self-reported risk aversion is the single most important determinant of

portfolio turnover and diversification for individual online investors.

Relative to the literature described above, our paper broadens the objectives under study so that

the focus on entertainment and gambling in the recent literature is imbedded in an analysis that also

examines other objectives such as saving for retirement, capital growth, and building a financial

buffer. The paper's examination of broad strategies in this context strikes us as new. Examples of

strategies are intuition, technical analysis, fundamental analysis, financial news, and advice from

brokers. As to psychological traits, the paper analyzes self-assessments of risk appetite, sophistication,

and ambition, all of which relate to issues addressed in the behavioral literature such as risk tolerance,

overconfidence, aspiration, and perceived competence.

2

We note that the idea of investors also deriving non-financial utility from their actions is not a recent one.

Markowitz (1952) already noted the “fun of participation” as a driving force of investing in the stock market.

3

Our analysis indicates that the performance of online investors’ portfolios, as measured by return,

factor risk, non-factor risk, and turnover are driven by the combination of objectives, strategies, and

personal traits. The paper contains new insights into the impact on investment activity from attributes

such as the objective of saving for retirement, the strategy of relying on intuition, and the

psychological trait involving ambition. Our findings support and extend results reported in the recent

literature. For example, consider investors whose primary objective is speculation. We confirm that

speculators turn their portfolios over more than other investors. We extend this finding to show that

relative to other online investors, self-identified speculators engage in more trading of options, earn

considerably lower returns (both gross and net of transaction costs) and bear more risk. Our results are

consistent with the well known finding for individual investors that turnover and returns are

negatively related, a property implicitly attributed to overconfidence. Notably, the paper provides

explicit evidence for this attribution in that relative to other online investors, speculators are especially

inclined to view themselves as very advanced. In respect to strategies, speculators who use technical

analysis have the worst returns by far. Not surprisingly, investors who employ technical analysis have

very high turnover and transaction costs, resulting in very low net returns. These results provide a

flavor of the findings reported in the paper. A fuller summary appears in the concluding section.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 describes how we measure

investors’ psychological profiles. Section 3 shows our data and method. Section 4 presents our results.

Section 5 relates the results to the underlying psychological theory. Section 6 concludes.

2. Measuring Investors’ Psychological Profiles

We determine individual investors’ psychological profile as follows. First, we measure investors’

sophistication in terms of their self-classification as either a novice, advanced or very advanced

investor, in line with studies investigating better than average overconfidence (Dorn and Huberman

2005; Glaser and Weber 2007b; Graham, Harvey, and Huang 2009). Second, we investigate investor

competence (Graham, Harvey, and Huang 2009) by studying the strategies investors use and the

amount of knowledge these require. Third, we identify the relative importance investors attach to

entertainment and gambling (Dorn and Sengmueller 2009; Kumar 2009) as well as sensation seeking

(Grinblatt and Keloharju 2009) through survey questions that pertain to primary investment objective.

Fourth, we measure investors’ risk appetite (Dorn and Huberman 2005; Dorn and Huberman 2009).

Fifth, in line with literature on the role of aspiration levels on investment decision-making (Shefrin

and Statman 2000; Statman 2002; Statman 2011) we measure investors’ ambition levels. Sixth, we

identify investors’ experience in terms of account tenure (Seru, Shumway, and Stoffman 2010).

3. Data and Method

Our analyses draw on transaction records of all clients and questionnaire data obtained for a sample of

clients of the largest online broker in The Netherlands. The broker is mainly known as a discount

4

broker, but started to offer investment advice in recent years. Due to trading restrictions, we exclude

accounts owned by minors (age <18 years). We also exclude accounts with a beginning-of-the-month

value of less than €250 and accounts owned by professional traders to ensure we deal with active

accounts owned by individual investors. Imposing these restrictions leaves 65,325 individual accounts

with over 9 million trades in common stock and derivatives from January 2000 until March 2006.

3

3.1 Brokerage Records

Opening positions and transaction records are available for all prospective participants of the survey.

The typical record consists of an identification number, transaction time and date, buy/sell indicator,

type of asset traded, gross transaction value, and transaction commissions.

3.2 Survey Data

In 2006, one of us designed and performed an online survey for all clients of the online broker. In

total, 6,565 clients completed the questionnaire. Among other questions, the questionnaire sought to

identify investors’ investment objectives, investment strategies, ambition levels, appetites for risk, and

their sophistication as reflected in their self-categorization into novice, advanced, or very advanced

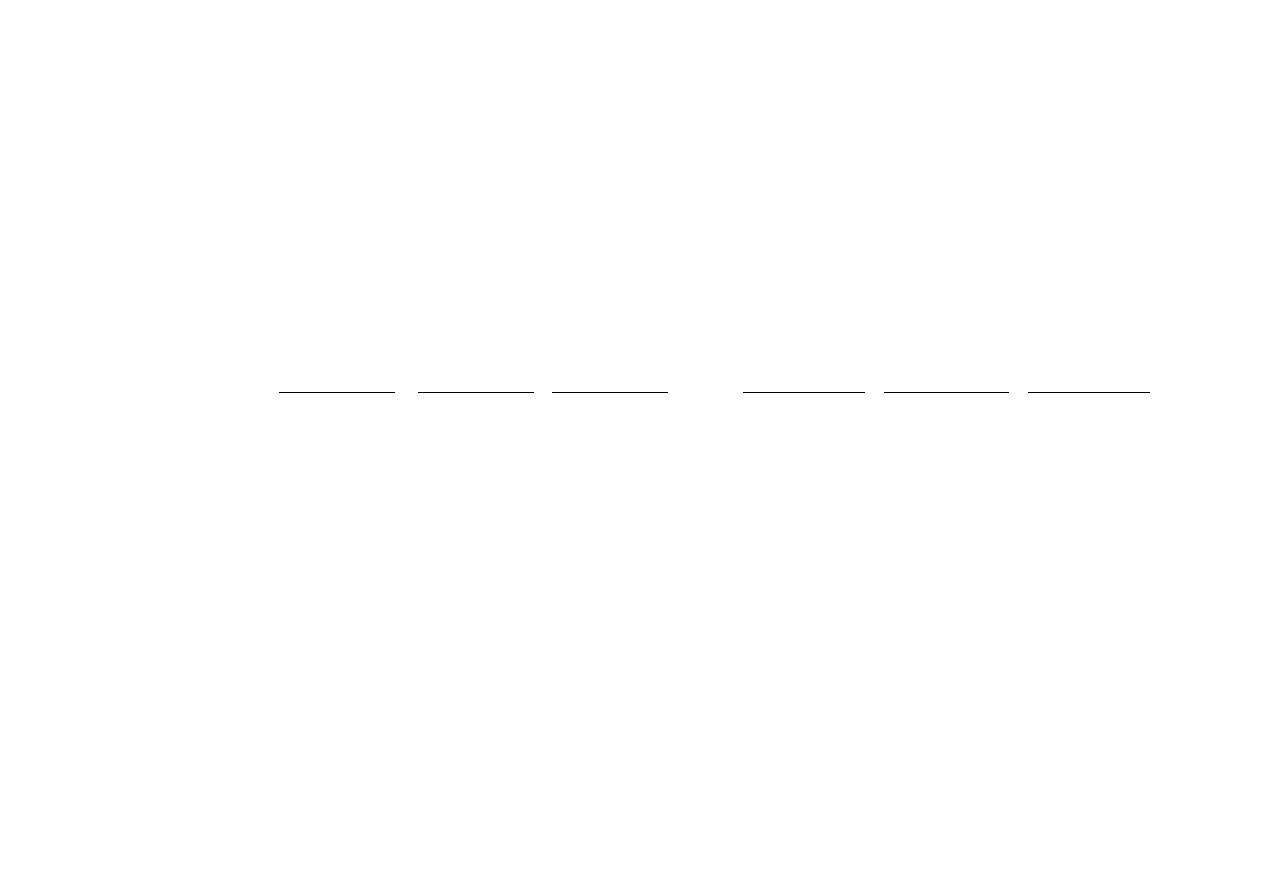

investor classes (see Figure 1).

After matching transaction records with questionnaire data, a sample of 5,500 clients and

corresponding accounts remain for which both transaction and survey data are available.

[Figure 1 about here]

3.3 Summary Statistics

In Table 1 we report descriptive statistics for the respondents (Panel A) as well as non-respondents

(Panel B) to the investor survey. Of the sample of investors for which both transaction and survey

data is available, 58% are male and the mean age is about 50 years. The mean (median) number of

trades over the sample period is 76.45 (30.00). Average (median) monthly turnover of common stock

is about 42% (11%), for derivatives average (median) monthly turnover is 16.5% (3.62%). The

average (median) portfolio value is €45,915 (€15,234). Combining the average portfolio value with

the total portfolio value of the average Dutch investor (Bauer, Cosemans, and Eichholtz 2009)

indicates that our average client invests more than three-fourths of her total self-managed investment

portfolio at this particular online broker. Although we have no information on these investors total

wealth including, for example, real estate and pension accounts, these numbers make it unlikely that

we investigate “play accounts” (Goetzmann and Kumar 2008).

4

Mean (median) trading experience is

3

As they constitute a negligible fraction of all trades in our sample, we follow Bauer, Cosemans and Eichholtz

(2009) and disregard any transactions in bonds and futures contracts.

4

In fact, 40.8% of our survey respondents only hold an investment account at this particular broker. Of the

respondents who also hold an investment account at another broker, 51.6% indicate that this comprises less than

5

about 40.21 (39.00) months. As compared to recent findings by Odean and Barber (2000) and

Goetzmann and Kumar (2008) our investors’ portfolios are better diversified, although still far from

well-diversified. The mean (median) number of stocks held by our investors is 6.57 (4.00) while the

mean (median) Herfindahl-Hirschmann Index (HHI) is 27.78% (21.14%). Comparing the HHI with

the normalized HHI (HHI*) indicates that investors’ portfolio weights are not uniformly distributed.

5

Mean (median) monthly returns over the sample period are -0.30% (0.30%). Risk appetite is relatively

high, with a mean (median) score of 5.31 (6.00) (1=very conservative, 7=very speculative).

A comparison between survey respondents (Panel A) and non-respondents (Panel B) shows that,

although the differences are relatively small, the clients who completed the survey tend to be

relatively sophisticated investors with a sizeable portfolio, which adds to the relevance of our study.

[Table 1 about here]

3.4 Measuring Investor Performance

Investor performance is defined as the monthly change in market value of all securities in an

investor’s account net of transaction costs. As performance is measured on a monthly basis,

assumptions have to be made considering the timing of deposits and withdrawals of cash and

securities. To be conservative, we assume that deposits are made at the start of each month and

withdrawals take place at the end of each month. Analyses assuming that deposits and withdrawals

are made halfway during the month yield similar results. Hence, we calculate net performance as

)

(

)

(

1

1

it

it

it

it

it

net

it

D

V

NDW

V

V

R

+

−

−

=

−

−

,

(1)

where V

it

is the account value at the end of month t, NDW

it

is the net of deposits and withdrawals

during month t, and D

it

are the deposits made during month t.

Gross performance is obtained by adding back transaction costs incurred during month t, TC

it

, to

end-of-the-month account value,

)

(

)

(

1

1

it

it

it

it

it

it

gross

it

D

V

TC

NDW

V

V

R

+

+

−

−

=

−

−

.

(2)

3.5 Attributing Investor Performance

To obtain investors’ abnormal performance, we attribute their returns to different risk and style factors

using the Carhart (1997) four-factor model. This model adjusts investor returns for exposure to market

(RMRF), size (SMB), book-to-market (HML), and momentum (UMD) factors. Following Bauer et al.

(2009), we construct these factors for the Dutch market, as our sample of investors mainly invests in

half of their total portfolio. As a robustness check, we compare the results of investors who only invest through

this particular broker with those who also have another broker, and find no significant differences.

5

HHI* measures HHI relative to a uniform benchmark, thereby facilitating comparisons across portfolios with

different numbers of stocks. The HHI*-benchmark value for a uniformly distributed portfolio is zero.

6

Dutch securities.

6

The market return in the RMRF factor is the return on the MSCI Netherlands equity

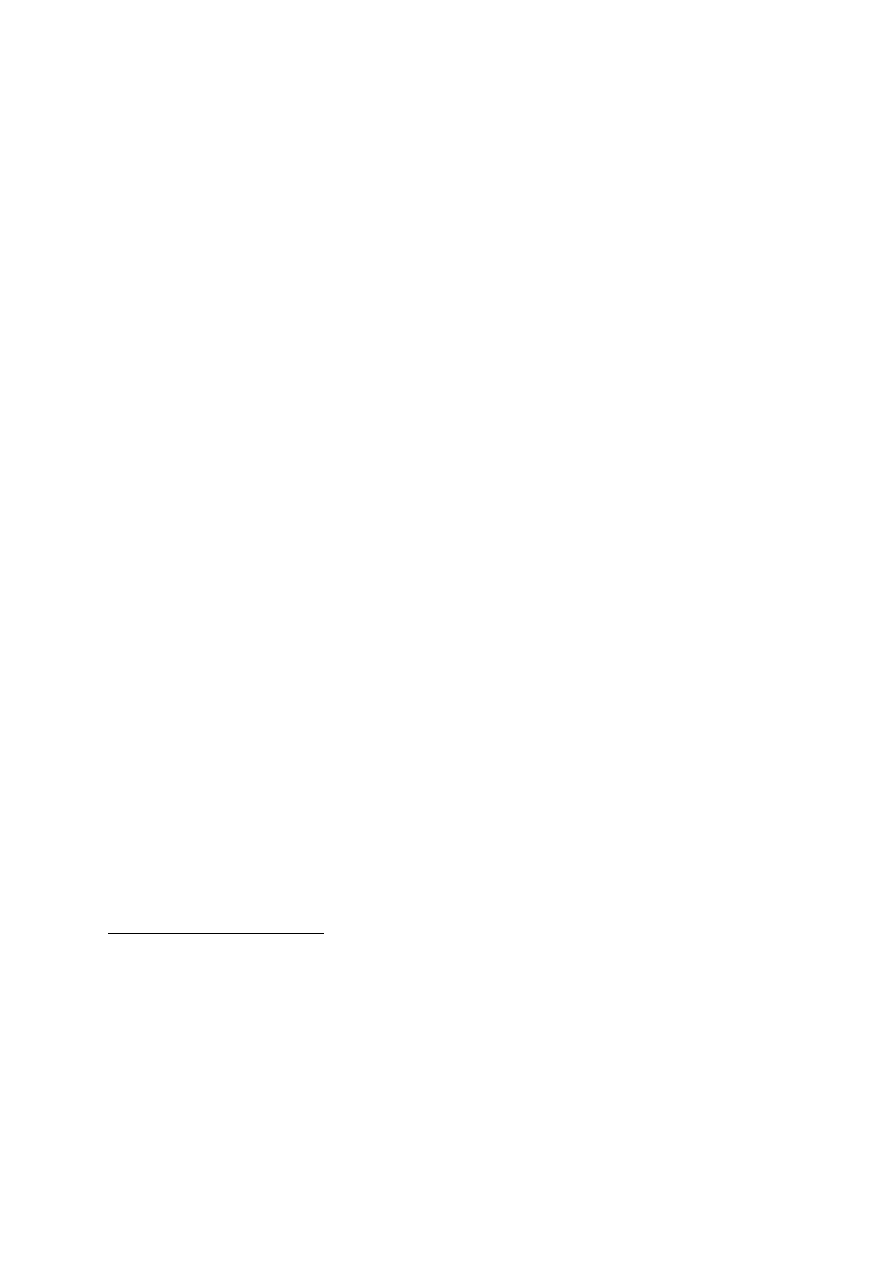

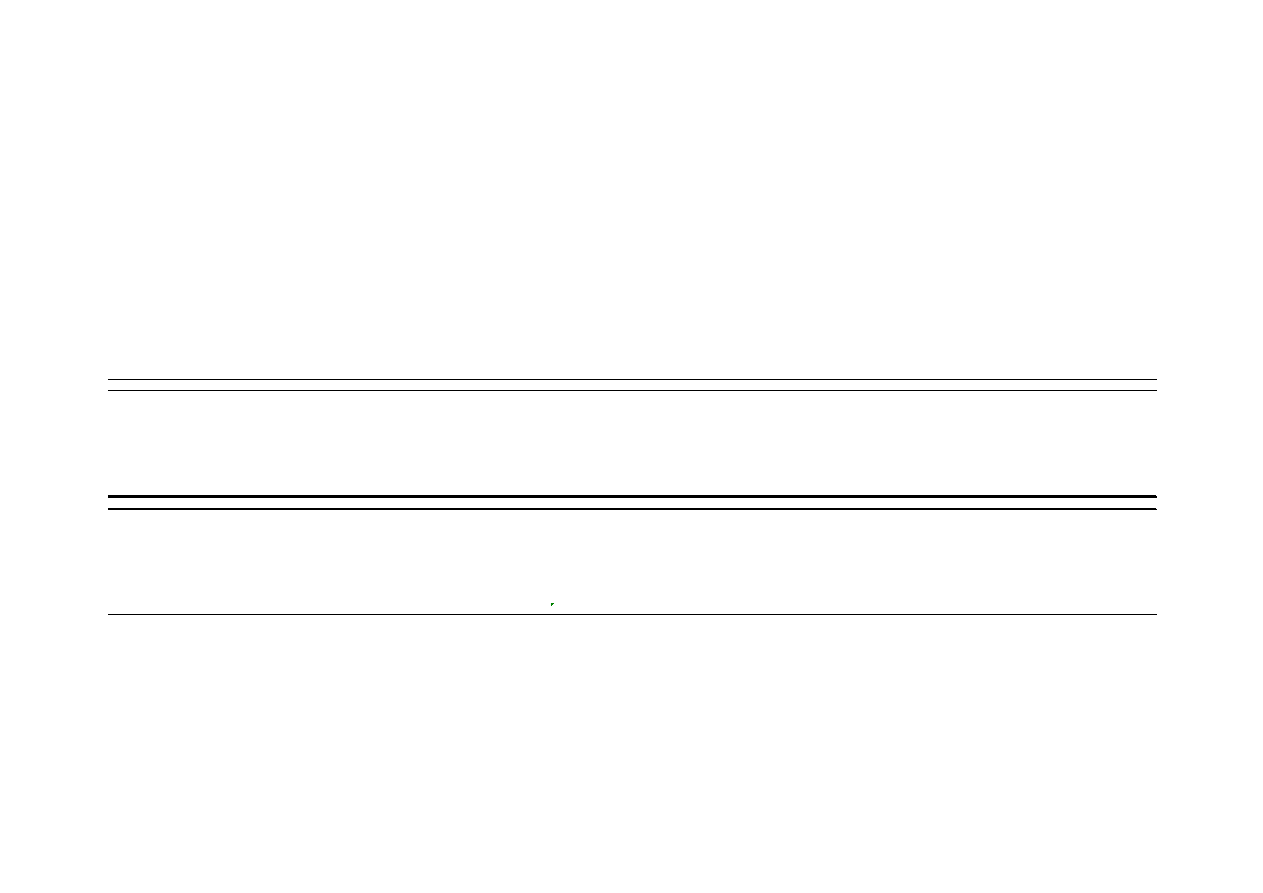

index. Figure 2 shows the performance of this index over the sample period. On average, the monthly

return on the Dutch market was -0.29% with a standard deviation of 6.73%. All factor-mimicking

portfolios are constructed according to the procedure by Kenneth French.

7

The following time series model is estimated to obtain risk and style adjusted returns:

∑

=

+

+

=

K

k

it

kt

ik

i

it

F

R

1

ε

β

α

.

(3)

In this model R

it

represents the excess return on investor i’s portfolio, β

ik

is the loading of portfolio i

on factor k, and F

kt

is the month t excess return on the k’th factor-mimicking portfolio. The intercept

α

i

measures abnormal performance relative to the risk and style factors. The factor loadings indicate

whether a portfolio is tilted towards market risk or a particular investment style.

[Figure 2 about here]

4. Empirical Results

We begin our empirical investigation by examining the distributions of individual investors’ traits,

such as risk appetite, ambition, and sophistication, their strategies, and their objectives. Next, we

study the interaction among these investors’ traits, the strategies they follow and the objectives they

choose. We then report regression results explaining turnover and return performance using investor

characteristics and traits, strategies, and objectives. Finally, we group investors into different

segments and compare investor traits, turnover, and return performance among these groups.

4.1 Traits, Strategies, and Objectives

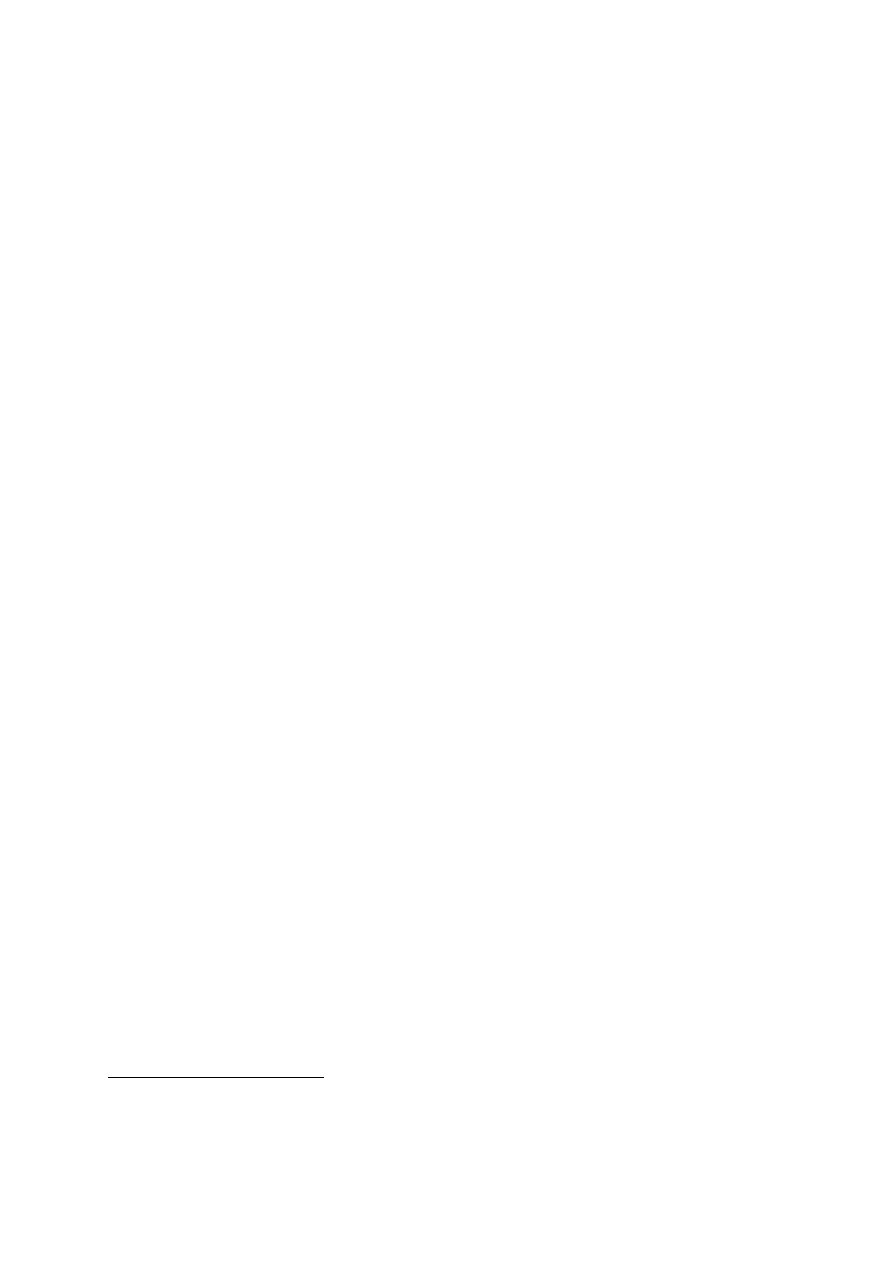

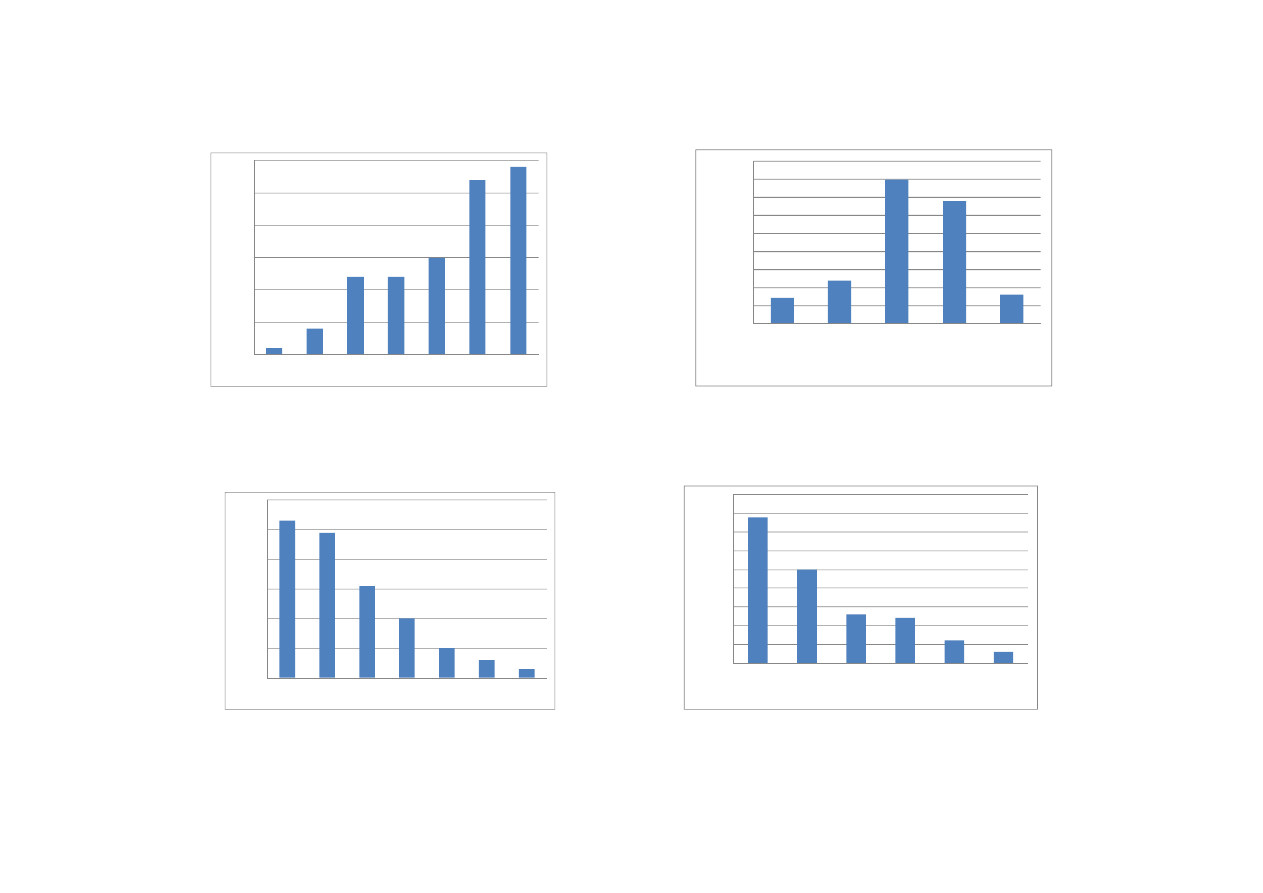

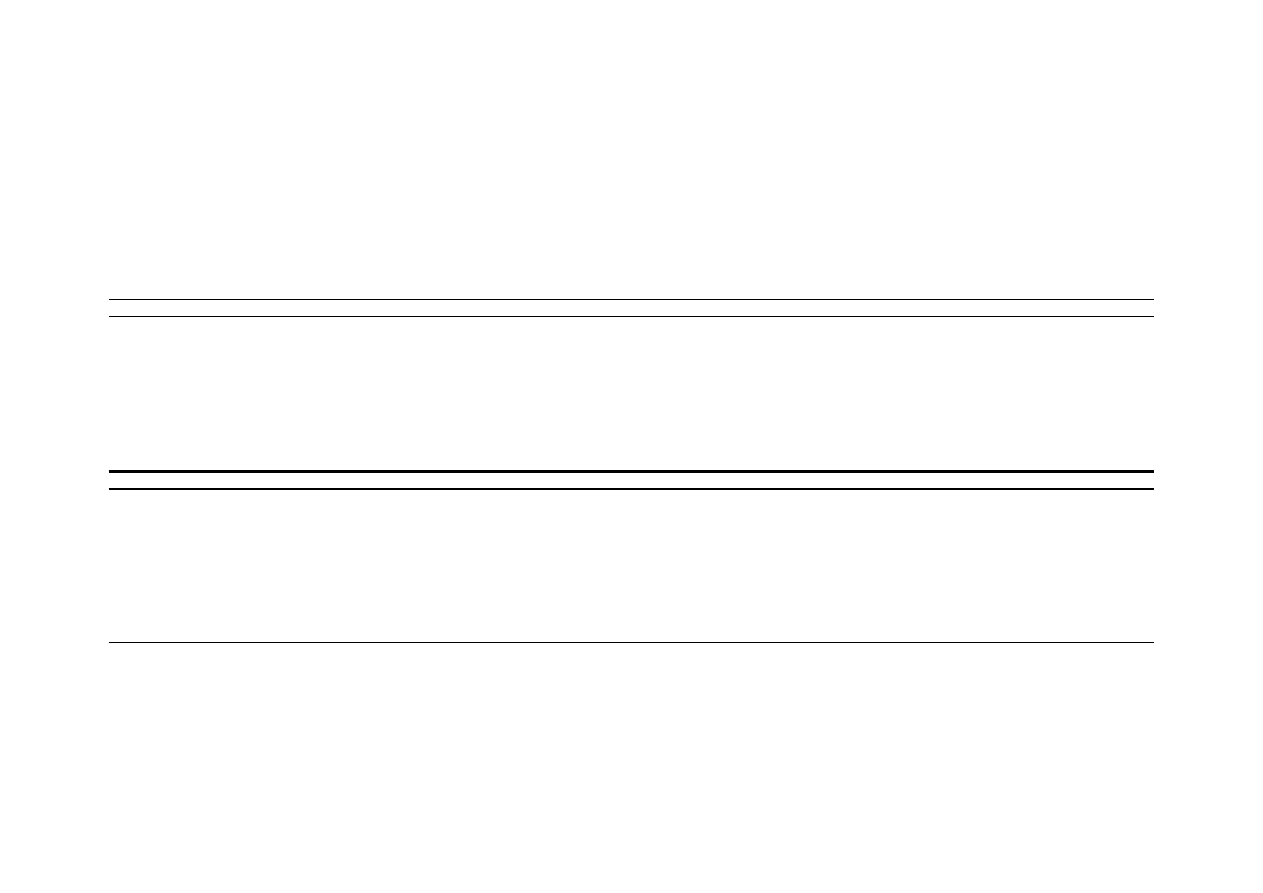

Figure 3 shows the distribution of investor age. Overall, the investors are either middle-aged or older,

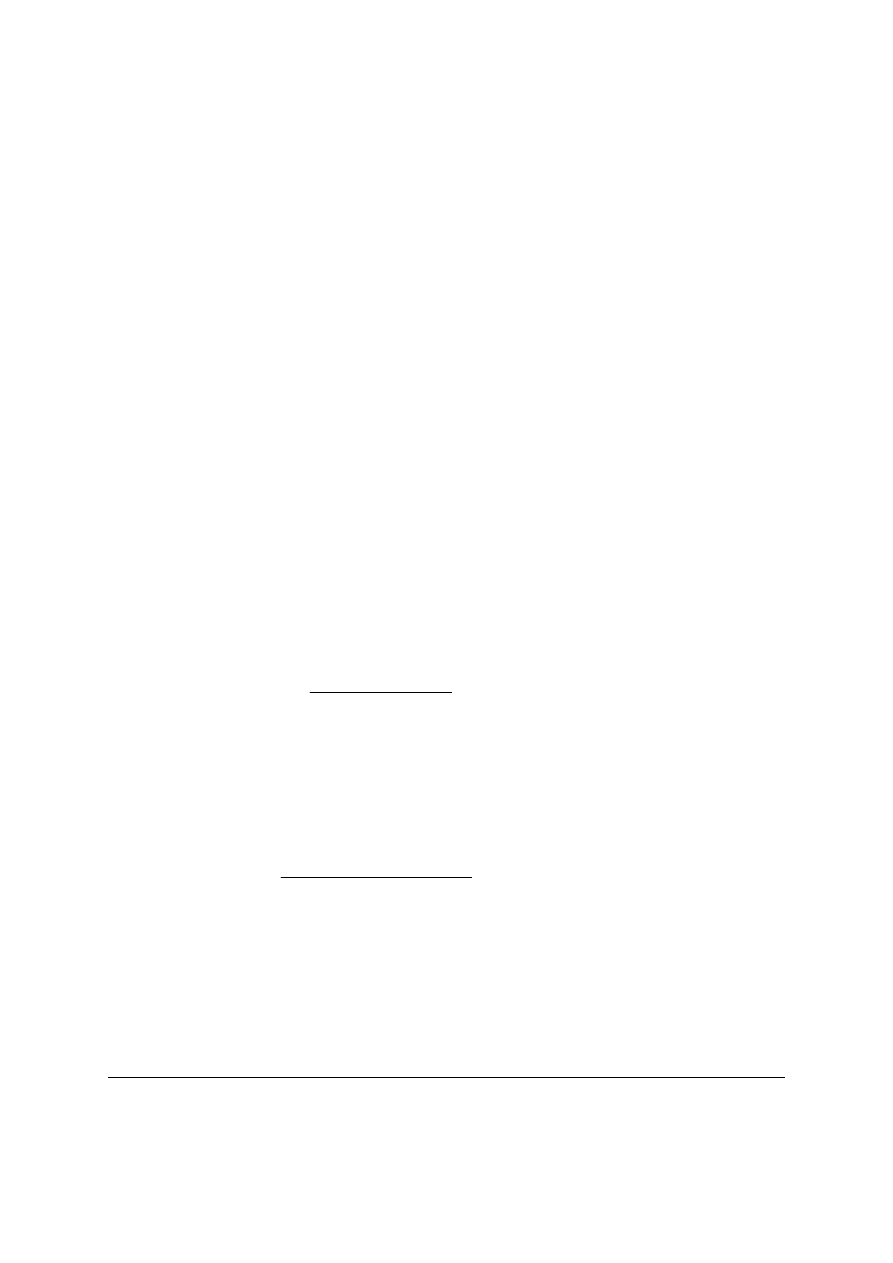

while only a small proportion of investors are under 30 years old. Figure 4 depicts investors’ self-

reported investment experience in years. Most investors report to have 5 or more years of investment

experience, while the proportion of inexperienced investors is small. Figure 5 shows the distribution

of investors’ self assessments of sophistication. From this figure it becomes clear that while the

majority of investors in our sample judge themselves to be advanced or very advanced, the most

prevalent group are novices. Figure 6 shows the distribution of investors’ risk appetite along a

continuum from very conservative to very speculative. It is striking to see that most investors classify

themselves as either speculative or even very speculative, while only few investors see themselves as

conservative or careful investors. Figure 7 displays the distribution of investors’ ambition level. Most

investors are either moderately or considerably ambitious. Figure 8 displays the strategies that

individual investors use to reach their investment decisions. Investors’ most popular strategy is to use

6

In terms of volume (value) 95% (85%) of all trades are transactions in Dutch securities. Hence, we find that

Dutch versions of the factor-mimicking portfolios lead to a better model fit than do international factors.

7

See http://mba.tuck.dartmouth.edu/pages/faculty/ken.french/data_library.html.

7

their own intuition, followed by financial news, technical analysis, fundamental analysis, professional

advice, and finally, tips from others (e.g., friends or family). Figure 9 depicts the most important

objective investors have regarding their investment account. Although achieving capital growth is the

most important goal, we note that about 38% of our sample invests either as a hobby or to speculate

on short-term stock market developments.

[Figures 3-9 about here]

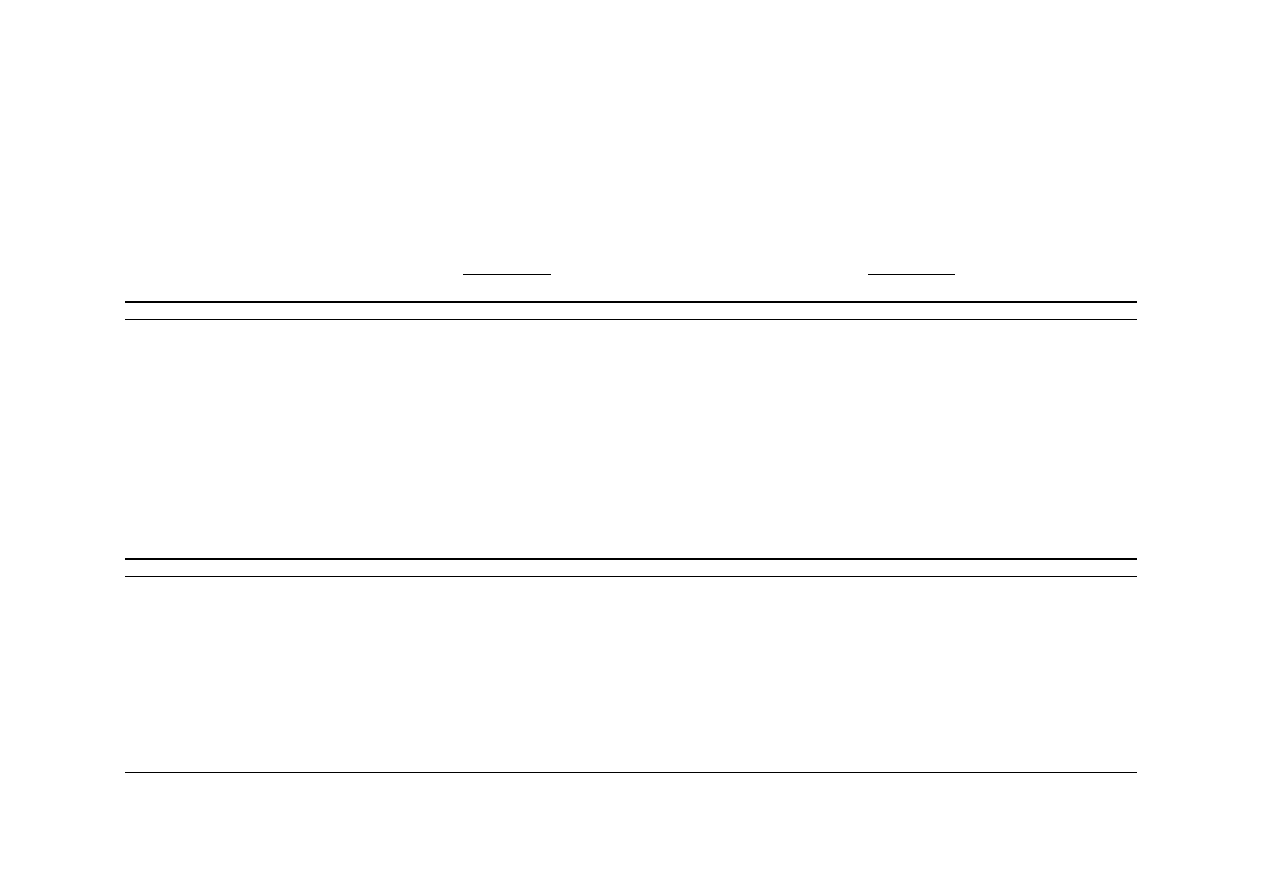

4.2 Interactions among Traits, Strategies, and Objectives

In this section we investigate the interactions among investor traits, objectives and strategies

by

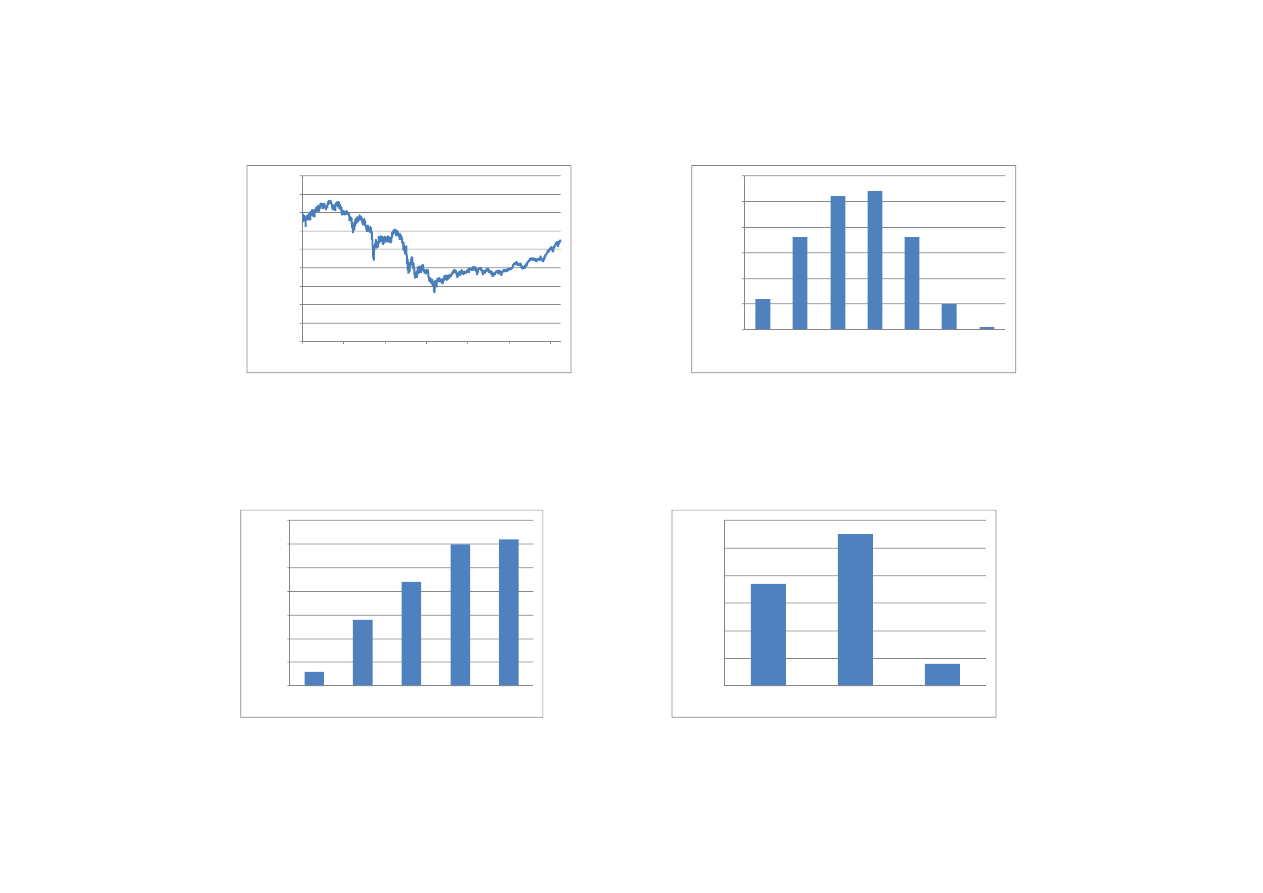

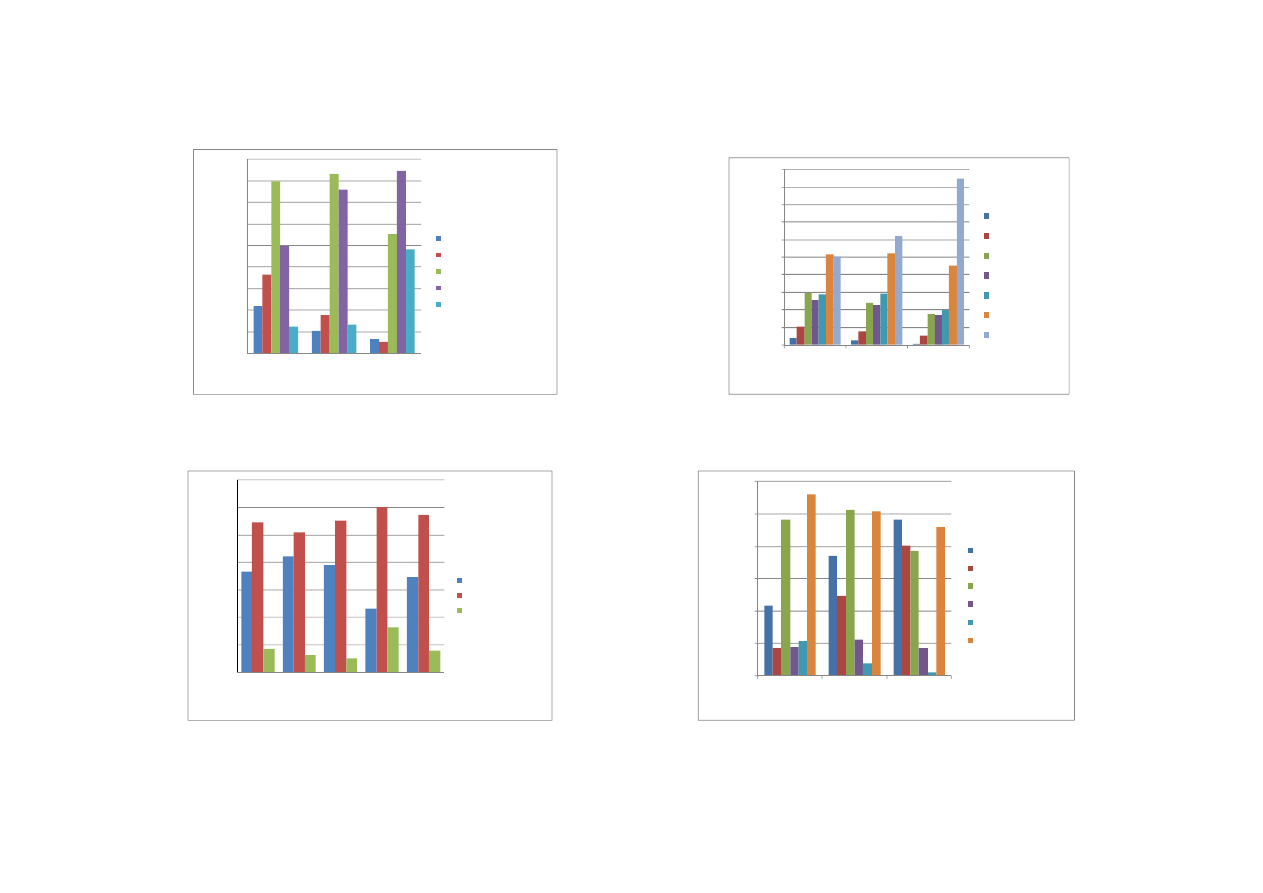

presenting cross-tabulating results. Figure 10 shows that the proportion of very ambitious investors is

higher for more sophisticated investors, while less sophisticated investors are less ambitious. Figure

11 shows that investors who judge themselves to be more sophisticated also have a higher risk

appetite. The high proportion of very advanced investors with a very speculative risk profile is

striking. Figure 12 shows sophistication level for the different objectives. Interesting findings are that

of all different objectives, investors that invest as a hobby have the highest proportion of novices,

while investors whose objective is to speculate have the highest proportion of investors who judge

themselves to be very advanced. Figure 13 shows the strategies that investors of different levels of

sophistication use to make their investment decisions. We find it noteworthy that although advanced

and very advanced investors more frequently use technical and fundamental analysis, while relying

less on tips from others and their intuition, the opposite is true for less sophisticated investors. Finally,

Figure 14 shows that the more ambitious investors become, the less use they make of their own

intuition and tips from others, and the more they use either technical or fundamental analysis.

[Figures 10-14 about here]

4.3 Explaining Investor Turnover: Regression Results

Table 2 first confirms previous findings that more experienced investors (Dorn and Huberman 2005)

and investors with higher past performance (Barber and Odean 2000) trade less frequently, while

investors that have a higher risk appetite (Dorn and Sengmueller 2009) trade more. Our findings add

to the existing literature in several ways. First, we find that investors with higher ambition levels and

investors who hold more concentrated portfolios trade more. Second, while wealthier investors have a

higher turnover of stocks, they actually have a lower turnover of derivatives. This finding suggests

that wealthier investors are more sophisticated and financially savvy, as prior research using similar

data reports that option trading hurts performance (Bauer, Cosemans, and Eichholtz 2009). Third,

adding investors’ objectives and strategies increases the explained variance in turnover and provides

additional insight into the drivers of trading. Both for stocks and derivatives, we find that investors

whose primary objective is speculating trade more. For stocks, we also find that investors whose

8

primary objective is capital growth or to save for retirement have lower turnover. Concerning

strategies, we find that both for stocks and derivatives, investors who use technical analysis trade

more. Investors who report relying on their intuition turn over their stocks more rapidly. Notably, the

use of fundamental analysis and financial news is negatively related to derivative turnover.

[Tables 2-5 about here]

4.4 Explaining Investor Performance: Regression Results

Table 3 (gross returns) first confirms previous findings that portfolio concentration (Goetzmann and

Kumar 2008) and stock turnover (Barber and Odean 2000) hurt performance, while wealthier

investors do better (Dhar and Zhu 2006). In addition we find that investors with more experience

(account tenure) achieve worse returns than investors with less experience, suggesting that experience

may lead to overconfidence (Barber and Odean 2001a; Gervais and Odean 2001). Indeed, we find

some evidence for such overconfidence as investors who report to be “very advanced” have a

significantly shorter account tenure (39 months) than those reporting to be “advanced” (42 months)

while the opposite result would be expected (t(3386) = 2.95, p = 0.003).

8

In addition, as our data is

from an online discount broker, investors with longer account tenure were first to adopt online trading

platforms. Prior research has identified online trading with behavioral phenomena such as self-

attribution bias, and illusions involving knowledge and control, which are known to reduce investors’

return performance (Barber and Odean 2001b; Barber and Odean 2002). In untabulated analyses, we

find that investor’s (online trading) experience is positively related to the standard deviation of their

gross and net returns and negatively related to the Adjusted R-squared of Carhart regressions. This

implies that experienced investors take both more total risk and more idiosyncratic risk. We find that

investors with higher risk appetite achieve higher gross returns. Investors’ objectives do not impact

their returns, but we add to the existing literature by finding that investors who use technical analysis

or professional advice to reach their investment decisions perform worse than those who do not.

Table 4 (net returns) shows a similar picture as Table 3, but makes clear that derivatives turnover

is especially detrimental to investors’ net return performance, although it had no impact on their gross

returns. This finding is in line with recent studies on option trading and individual investor

performance (Bauer, Cosemans, and Eichholtz 2009).

Table 5 (Carhart’s alpha) again shows that more experienced investors and investors with higher

turnover achieve lower returns, while wealthier investors achieve better returns. In addition, we find

that age has a negative impact on investors’ risk- and style adjusted net performance. After adjusting

for risk- and style tilts, investors’ net performance is no longer affected by their strategies.

8

We find a strong relationship between sophistication and self-reported investment experience: more advanced

investors report a longer experience. Interestingly, however, even after 5 years of self-reported investment

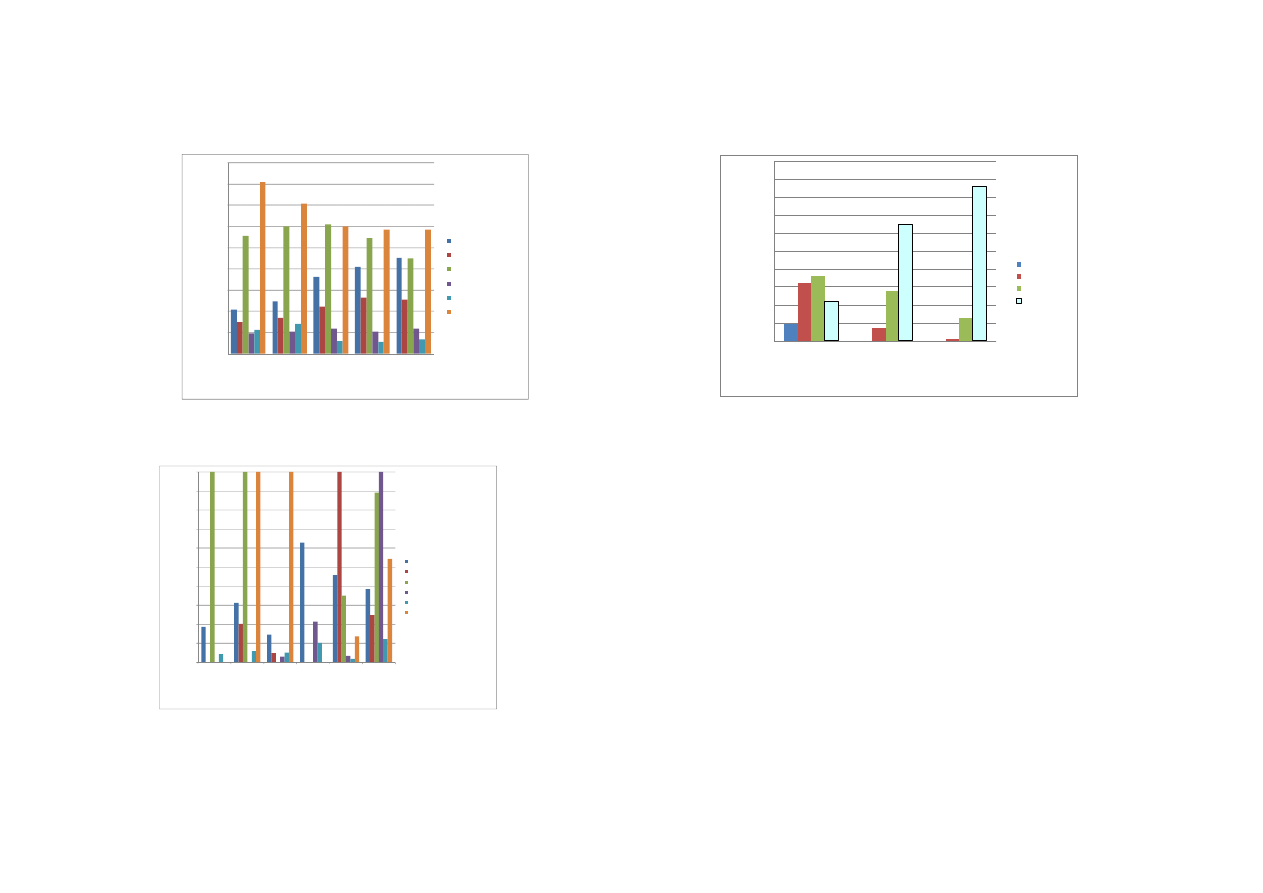

experience, there are still a substantial number of investors who consider themselves to be novices (Figure 15).

9

[Figure 15 about here]

4.5 Segmenting Investors

To highlight the associations among investors’ traits, strategies, and objectives in a more formal

manner, we segment the group of 5,500 investors for which we obtained both transaction and survey

data into groups based on their investment objectives and strategies (cf. Bailey, Kumar, and Ng 2010).

While the investors in our sample typically have only one investment objective, they combine

different strategies to attain this objective. Hence, we use univariate sorting to distinguish segments

based on investment objective and cluster analysis to discern segments based on investment strategy.

The univariate sorting results indicate five segments of investors based on their primary

investment objective. These segments are labeled Capital Growth, Hobby, Saving for Retirement,

Speculation

, and Building Financial Buffer.

To group together investors with similar scores on certain (combinations of) strategies, we use a

non-hierarchical cluster analysis following Hair et al. (1998). Using this method, differences between

segments in terms of scoring are maximized and within segments minimized. This procedure leads to

six segments, which we call Financial News, Financial News and Intuition, Intuition, Technical

Analysis Mix

, Fundamental Analysis Mix, and Financial News, Intuition, and Professional Advice.

Figure 16 shows the distribution of strategy usage within these different segments.

Table 6 reports descriptive statistics for these segments in regard to a number of brokerage

account variables, while Table 7 does the same for the survey variables.

[Tables 6 and 7 about here]

[Figure 16 about here]

4.5.1 Profiling Investor Segments based on Investment Objective

Table 6 shows that male investors are especially well represented in the segments Hobby and

Speculation

. The latter segments also contain the youngest investors, whereas those in the segment

Speculation

also trade most heavily during the sample period. Monthly turnover of stocks is highest in

the segment Speculation and lowest in the segment Saving for Retirement. Monthly turnover of

derivatives is highest in the segment Speculation, and lowest in the segment Building Financial

Buffer

. Investors in the segment Capital Growth have the largest portfolio value while Hobby

investors have the smallest. Investors Saving for Retirement are most experienced and best diversified

both in terms of number of stocks and the HHI, while investors in the segment Speculation are least

experienced and less diversified. The profiles of the segments Speculation and Hobby thus obtained,

containing younger male investors who overtrade and underdiversify, are in line with recent findings

on speculative trading as gambling (Kumar 2009) or entertainment (Dorn and Sengmueller 2009).

10

Table 7 demonstrates that investors in the segment Speculation are most ambitious, have the

greatest risk appetite, reports to have the lowest percentage of novice investors, and the highest

percentage of advanced and very advanced investors, respectively. Together with the high turnover

and dominance of males in this segment, these findings confirm and enrich earlier work that finds that

especially male investors are subject to overconfidence and trade excessively (Barber and Odean

2001a). Additionally, these findings confirm the prediction by Statman (2002) that investors who

perceive investing as playing the lottery may have particularly high aspiration levels and be subject to

overconfidence. Not surprisingly, investors in the segment Saving for Retirement have lower ambition

levels, lower risk appetite and are more modest about their self-assessed level of sophistication.

4.5.2 Profiling Investor Segments based on Investment Strategy

Table 6 shows that the fraction of males is highest in the segment Fundamental Analysis Mix and

lowest in the segments Financial News and Financial News, Intuition, and Professional Advice. The

number of trades during the sample period is highest for investors in the segment Fundamental

Analysis Mix

and lowest in the segment Intuition. The previous combination of gender and turnover is

consistent with earlier work by Barber and Odean (2001a) who find that relative to women, men are

overconfident and trade heavily. The combination of using fundamental analysis and excessive

trading is in line with our expectations that especially investors who feel they have more complete

information are likely to make bold forecasts and overcome their status quo bias, leading to less timid

choices in terms of transaction frequency (cf. Kahneman and Lovallo 1993). Average age is highest in

the segment Financial News, Intuition, and Professional Advice and lowest in the segment Intuition.

Monthly turnover of stocks is highest in the segment Financial News and Intuition and lowest in the

segment Technical Analysis Mix. Interestingly, however, the segment Technical Analysis Mix has the

highest turnover of derivatives, while the segment Financial News has the lowest. The segment

Fundamental Analysis Mix

has the highest portfolio value while the segment Intuition has the lowest.

Investors in the segment Financial News are most experienced while those in the segment Technical

Analysis Mix

are least. We find interesting differences between segments with regard to portfolio

diversification. The segment Fundamental Analysis Mix is best diversified, while the segment

Intuition

has the worst diversification. Investors who rely on intuition might have less conviction in

their capabilities than investors employing fundamental analysis, as they have less complete

information, resulting in conservative forecasts.

Table 7 demonstrates that investors in the segment Fundamental Analysis Mix have the highest

ambition level, while investors in other segments, such as Intuition and Financial News have more

modest ambitions. In line with the previous results, investors in the segment Fundamental Analysis

Mix

have the greatest risk appetite, whereas investors in the segment Financial News have the lowest

risk appetite. Finally, whereas the segments Fundamental Analysis Mix and Technical Analysis Mix

have the highest percentage of investors who regard themselves as very advanced, these numbers are

11

considerably lower in the other segments, reaching a minimum in the segment Financial News. The

lower score of the latter category of investors indicates that they may be less likely to be

overconfident about their abilities. Instead of trying to make an independent estimate of a company’s

attractiveness using, for example, fundamental analysis, they rely on widely available financial news.

4.6 Performance per Investor Segment

In this section we compare the raw returns and Carhart alphas of the different segments of investors

(Table 8). We expect important differences between segments due to the previously identified

differences with respect to characteristics obtained from the brokerage account data (e.g., turnover,

age, transaction frequency) as well as traits obtained from our investor survey (e.g., ambition level,

risk appetite). Interestingly, some groups of investors were able to achieve higher returns than the

market during our sample period, both gross and net of fees, although we note that return standard

deviations were all higher than the market standard deviation, with Carhart’s alpha being negative

across all investor segments.

[Table 8 about here]

4.6.1 Segments based on Investment Objectives

Panel A of Table 8 shows that the segment Speculation has the worst raw return (gross), while the

segment Capital Growth does best. The average investor in the segment Speculation loses 0.38% per

month in gross terms, whereas the average investor in the segment Capital Growth gains 0.68%.

The right hand side of Panel A shows that the performance difference between segments of

investors widens when transaction costs are taken into account. The return to the segment Speculation

incurs the most transaction costs, which is plausible considering this segment’s high turnover. The

raw net return of this segment is -2.22% per month, whereas the performance of the segment Capital

Growth

is still positive with 0.22%.

After also adjusting for both risk and style tilts, the segment Capital Growth still achieves the best

performance with a net alpha of -0.40% per month, whereas the segment Speculation remains the

worst performer with a net alpha of -1.28%. The latter result is in line with the traits of this segment’s

investors as obtained both from their brokerage account as well as investor survey data. Investors

whose objective is to speculate have high ambition levels, high risk appetite, high turnover, and judge

themselves to be very advanced. These traits are typical for overconfident investors who overtrade

and underperform (Barber and Odean 2001). In addition, the factor loadings show that these investors

heavily invest in small cap stocks, which may be a risky strategy in combination with their lower level

of diversification. Finally, the standard deviation of returns suggests that investors in the segment

Speculation

take the most risk while those in the segment Capital Growth take the least risk (in terms

of total risk). In addition, the low Adjusted R-squared values of the Carhart four-factor regression

12

suggest that for investors in the segments Hobby and Speculation idiosyncratic and thus

uncompensated risk is largest, while this is smaller for investors in the other segments.

4.6.2 Segments based on Investment Strategy

Panel B of Table 8 shows that the segment Technical Analysis Mix has the worst raw return (gross),

while the segment Financial News and Intuition does best, closely followed by Fundamental Analysis

Mix

. An average investor in the segment Technical Analysis Mix gains only 0.07% per month in gross

terms, whereas an average investor in the segment Financial Analysis and Intuition gains 0.86% and

Fundamental Analysis Mix

0.76%, respectively.

At the right, Panel A shows that, after taking transaction costs into account, the segment Technical

Analysis Mix

achieves the lowest returns and the segment Financial News and Intuition achieves the

highest returns. The raw net return of the segment Technical Analysis Mix becomes negative at

-0.92% per month, while the performance of the segment Financial News and Intuition stays positive

at 0.13%.

This pattern remains the same after adjusting for risk and style tilts, although the difference

between segments narrows. The segment Financial News and Intuition achieves the best performance

with a net alpha of -0.46%, closely followed by the segment Fundamental Analysis Mix, which

obtains a net alpha of -0.47%. The segments Technical Analysis Mix and Financial News, Intuition,

and Professional Advice

are the worst performers, having a net alpha of -0.73% and -0.71% per

month, respectively. The superior performance of the segments Financial News and Intuition and

Fundamental Analysis Mix

is interesting and suggests some stock-picking skills. After all, these

investors’ stock choices must be good enough to overcome the detrimental effect of the relatively high

level of transactions of these segments. The inferior performance of the segment Financial News,

Intuition, and Professional Advice

is remarkable and suggests that the advice of investment

professionals may not be very helpful for the performance of online investors’ portfolios, but is

associated with a relatively high number of transactions and turnover. Finally, the inferior

performance of the segment Technical Analysis Mix illustrates the limited usefulness of past stock

market information for future return performance. In addition, this segment trades heavily in

derivatives, which has been proven to often hurt performance (Bauer, Cosemans, and Eichholtz 2009).

Although the difference in total risk (standard deviation of returns) does not differ significantly

between the segments based on strategy, idiosyncratic risk does differ significantly, as indicated by

the Adjusted R-squared values of the Carhart four-factor regression. The low Adjusted R-squared

values suggest that for the segment Technical Analysis Mix, uncompensated risk is largest.

5. Behavioral Explanations: Underlying Psychology

In keeping with earlier literature on matched survey/trading data, we find strong support for the

importance of four traits in respect to the decisions online investors make about their portfolios and

13

trading activity: overconfidence, competence, entertainment/speculation, and risk appetite. Our

analysis confirms previous findings documenting that these variables are positively related to turnover

and negatively related to performance. Below, we place our results in the context of these traits.

5.1 Overconfidence

There are two versions of overconfidence identified by the behavioral decision literature,

overconfidence about ability and overconfidence about knowledge. Glaser and Weber (2007b) find

that overconfidence about ability is germane to investor behavior, but not overconfidence about

general knowledge. Overconfidence about ability is typically task specific and involves a person

viewing themselves as better at that task than they actually are. It is sometimes referred to as the

“better than average” effect because in surveys about relative ability, more than half of respondents

view themselves as above average, even when average is explicitly defined as the median.

We suggest that degree of self-assessed sophistication reflects overconfidence about ability. Our

analysis provides insights into the interaction of sophistication with investment experience, aspiration

(ambition), risk appetite, objective, and strategy. Notably, online investors viewing themselves as very

advanced are also the most ambitious (Figure 10) and have the highest risk appetites (Figure 11). As

shown by Figure 12, 25% of these investors indicate that their primary objective is speculating,

compared to 14% of all the investors in our sample. In regard to strategies, investors viewing

themselves as very advanced are much more inclined to use technical analysis and fundamental

analysis, and less inclined to rely on intuition than investors viewing themselves as novices or

advanced (Figure 13). As for experience, novice investors are quite varied in their self-reported

investment experience, very advanced investors are almost exclusively dominated by investors with

more than five years of experience, while advanced investors lie somewhere in between (Figure 15).

Notably, the results we report in section 4.4 suggest that investment experience might capture an

aspect of overconfidence not fully accounted for by sophistication.

5.2 Self Perceptions of Competence

Perceived competence reflects the degree to which investors view themselves as being knowledgeable

or familiar with the securities in their portfolios. In

this

regard,

competence

is

effectively

overconfidence about knowledge, reflecting familiarity bias. See Slovic and Corrigan (1973) who

study how amount of racing sheet information impacts the confidence and accuracy of horse race

handicappers.

As a concept, competence is one facet of the notion “bold forecasts, timid choices” introduced by

Kahneman and Lovallo (1993). This concept combines two conflicting features that have been

identified in the behavioral literature. The first feature pertains to biases such as excessive optimism,

overconfidence, and familiarity which predispose a decision maker to make bold forecasts. The

second feature pertains to regret avoidance, hindsight bias, ambiguity aversion, and loss aversion

14

which predispose a decision maker to maintain the status quo. Individuals whose behavior exhibits

both features are said to produce bold forecasts but make timid choices.

We suggest that strategy combinations capture familiarity bias, largely through their dependence

on financial news in combination with other choices. For example, we hypothesize that investors who

rely on financial news alone will feel more competent than investors who rely on intuition alone.

Similar reasoning leads us to suggest that investors who combine financial news and intuition will feel

more competent than investors who rely on financial news alone. Likewise, investors who combine

financial news, intuition, and professional advice will feel more competent than investors who only

combine financial news and intuition.

Graham et al. (2009) hypothesize a positive relationship between competence and trading volume.

This hypothesis would lead us to expect that for the four strategy segments discussed in the previous

paragraph, total turnover would be ranked highest for Financial News, Intuition, and Professional

Advice

, second highest for Financial News and Intuition, second lowest for Financial News alone, and

lowest for Intuition alone. We find that this is true with one exception. The one exception is that

turnover for the strategy segment Intuition is slightly greater than turnover for the segment Financial

News

. Interestingly, no investors in the segment Intuition rely on financial news, and vice versa.

We believe it is reasonable to suggest that investors using either technical analysis, fundamental

analysis, or both are more inclined to judge themselves as being more competent than other investors.

This is because the use of these techniques requires some level of familiarity with specific (company)

details, such as price histories, financial ratios, etc. In this regard, 35% of investors in the strategy

segment Fundamental Analysis Mix report relying on financial news, much lower than any of the

three segments with a strong association to financial news. If financial news were the only basis for

competence, this feature would predict that turnover would be lower for the segment Fundamental

Analysis Mix

than any of the financial news segments. Indeed, the segment Fundamental Analysis Mix

features more turnover than the segment associated with Financial News only. We view this as

evidence that using fundamental analysis is positively related to (perceived) competence.

There is reason to believe that professional advice (from brokers) contributes to competence in a

major way. The two segments most associated with professional advice are (1) Financial News,

Professional Advice, and Intuition

, and (2) Technical Analysis Mix. Every investor in the former

segment, and 21% of investors in the latter segment, use professional advice. These two segments

feature the most and second most total turnover.

The bold forecasts, timid choices perspective suggests that investors who view themselves as

more competent will hold more securities than investors who view themselves as less confident. As

can be seen from Table 6, this is a feature of our data. Notably, investors in the segment intuition hold

the least number of securities in their portfolios, whereas investors in the segment fundamental

analysis mix hold the most securities. This property is mirrored by HHI*. As noted by Goetzmann and

Kumar (2008), investors who increase the number of securities in their portfolio do not necessarily

15

become more diversified because of the tendency to add new securities that are similar to securities

already in the portfolio. This feature is consistent with familiarity bias, a point made by Graham et al.

(2009). As we discuss in section 5.4 below, idiosyncratic risk can be measured by Adjusted R-squared

in Table 8, and is highly pertinent to degree of diversification.

From a behavioral perspective, intuition corresponds to psychological concepts such as

representativeness and the affect heuristic. Representativeness refers to overreliance on stereotypes.

An example of an intuitive rule which reflects representativeness is “good stocks are stocks of good

companies.” See Solt and Statman (1989). The affect heuristic stipulates that in their memories,

people associate degrees of goodness (affect labels) to objects. Doing so provides the basis for snap

decisions, when it is too costly to take the time to analyze alternatives. An example of a rule reflecting

the affect heuristic is “buy stocks of companies whose names you both recognize and have made

strong positive associations with in your mind.” See Statman (2010) for a discussion of the affect

heuristic.

Shefrin and Statman (1995) find that reliance on the heuristic “good stocks are stocks of good

companies” associate good stocks with large companies and low book-to-market equity. In this

regard, Table 8 shows that investors belonging to the segment Intuition have the highest loading for

the size factor SMB (0.67) and the lowest loading for the book-to-market equity factor HML (0.21).

An interesting difference between the segment Intuition and the segment Technical Analysis Mix

concerns views about momentum. In Table 8, the loading on the momentum factor UMD for the

segment Intuition is -0.06, whereas for the segment Technical Analysis Mix the loading is 0.02. This

suggests that investors in the segment Intuition exhibit the behavioral bias gambler’s fallacy in that

they predict unwarranted return reversals, whereas investors in the segment Technical Analysis Mix

follow the technical maxim “the trend is your friend,” and predict momentum. The most important

difference between the compositions of these two segments is that all investors in the segment

Intuition

rely on their own intuition, although 15% also report using technical analysis. However, in

the segment Technical Analysis Mix, 63% use technical analysis, but none rely on their intuition.

5.3 Entertainment, Speculation, and Other Objectives

Our study supports the finding by Dorn and Sengmueller (2009) that investors who report enjoying

investing or gambling turn their portfolios over at roughly twice the rate of their peers (Table 6). In

this regard, we identify the objective “hobby” with “entertainment” and “speculating” with

“gambling.” Notably, speculating and hobby respectively have the highest and second highest rates of

total turnover for all objectives. Our study adds to the literature by distinguishing between speculating

and hobby, and by focusing on the properties associated with other objectives.

We view speculating as being especially associated with lottery-like returns, which is to say return

distributions that feature positive skewness. In contrast, we suggest that those who invest primarily as

a hobby focus on the thrill of picking winners, but attach less importance to positively skewed returns.

16

We do find that investors whose primary objective is speculating differ in interesting respects

from investors whose primary objective is entertainment. Consider the peer group for speculating and

hobby. The findings in Table 6 imply that members of the segment Speculation turn their portfolios

over at 2.6 times the peer group average, whereas for the Hobby segment, the corresponding figure is

considerably lower, at 1.4. Moreover, when it comes to the component of turnover associated with

derivatives, the corresponding ratios are 3.2 for Speculation and 1.5 for Hobby. These ratios support

the contention that speculators seek positively skewed returns more than other investors.

The sophistication profiles for the segments Speculation and Hobby are dramatically different.

The most prevalent investors in the speculating group rate themselves as very advanced, whereas the

most prevalent investors in the hobby group rate themselves as novices. The two groups also differ

dramatically when it comes to ambition. The most prevalent investors in the speculating group are

associated with the highest level of ambition, whereas for the hobby group, the most prevalent

investors are associated with the lowest level of ambition. Where the two groups do feature agreement

is risk appetite and diversification. The most prevalent investors in both groups feature the highest

risk appetite and the lowest number of stocks held. Notably, the hobby group holds the least number

of securities and has the highest value for HHI* (Table 6). While it might seem surprising that the

hobby group is less diversified than the speculating group, bear in mind that competence might be

playing a role here. The hobby group is less prevalent in segments where investors rely heavily on

technical analysis and fundamental analysis than the speculating group. In addition, the hobby group

is dominated by investors who view themselves as novices whereas the speculating group is

dominated by investors who view themselves as very advanced.

About 38% of our sample identify speculating and hobby as their primary objectives. When we

examine the other objectives, we find that the relationship between objectives and strategies is weak

in the sense that investors within the different objective groups choose strategies in similar ways. This

is not to say that there are no differences, only that the differences are not stark. For example,

investors in the speculating group lean to technical analysis more than do other groups. Investors in

the capital growth group lean to fundamental analysis more than do other groups. Investors in the

financial buffer group lean more both to financial news and own intuition than other groups.

Recall that capital growth, not speculation or hobby, is the most prevalent investor objective,

being associated with a little less than 40% of the investors in our sample. Capital growth is certainly

different from saving for retirement or building a financial buffer, in that precautionary saving and

retirement saving correspond to more specific goals. Yet, investors in this group earn the highest

returns, both gross and net, and surprisingly experience the lowest return standard deviations. This is

the case even though they are the worst diversified (as measured by HHI*) (Tables 6 and 7). Notably,

they turn their portfolios over much less than hobbyists and speculators, about the same as those

building a financial buffer, but considerably more than investors primarily saving for retirement.

17

What then distinguishes the capital growth group? In terms of psychological traits, the capital

growth group is more ambitious than investors building a financial buffer and saving for retirement,

but with a lower risk appetite. As we shall see next, risk appetite is particularly significant in this

regard, and is the dominant feature differentiating capital growth investors from the other two groups.

5.4 Risk Appetite and Aspiration

We find that differences in risk appetite impact both investor behavior and returns. The findings

reported in Tables 3 and 4 lead us to suggest that risk appetite is positively related to gross returns, but

not statistically significant to net returns. In this section, we provide a perspective suggesting that the

impact of risk appetite across objectives is negative. Our analysis suggests that at best, investors earn

no compensation for risk-bearing. We also suggest that other investor traits are equally important

drivers of investor behavior.

Our measure of risk appetite reflects a mixture of the traditional concept of risk aversion and the

behavioral concept of loss aversion (see Figure 1). We find that investors with different objectives do

differ significantly in their risk appetites. From lowest to highest, risk appetite ranks the segments

according to objectives as follows: Saving for Retirement, Building Financial Buffer, Capital Growth,

Hobby,

and Speculation. Viewed through the lens of objectives, realized risk is positively related to

risk appetite. That is, objectives associated with low risk appetites tend to experience lower return

standard deviations than investors with higher risk appetites (Tables 7 and 8). The results in Table 8

indicate that when viewed through the lens of objective, the relationship between risk and return is

negative, in the sense that the investors who earn the largest returns bear the least risk, as measured by

the return standard deviation of their portfolios. This statement holds true for both gross and net

returns. A simple OLS regression of net return on return standard deviation features a slope

coefficient of -0.3 (t = -7.0). For gross returns, the coefficient is -0.67 (t = -8.0).

Interestingly, the Capital Growth group appears to bear the least idiosyncratic risk (as measured

by Adjusted R-squared). Recall from Figure 9 that this group is not only the most common primary

objective, but comprises almost 40% of the sample. Notably, investors whose primary goal is

Speculation

bear the highest risk and earn the lowest returns. This finding is consistent with the notion

that speculators might be risk seeking and extends Dorn and Sengmueller (2009) by showing that

speculators might be willing to pay a premium to take risk, rather than shed risk. An alternative

explanation is, of course, that speculators are not risk seeking but instead make serious errors when

judging risk and/or expected return.

From lowest to highest, risk appetite ranks the segments according to strategies as follows:

Financial News, Financial News and Intuition, Financial News, Intuition, and Professional Advice,

Technical Analysis Mix, Intuition,

and Fundamental Analysis Mix. Regressing returns of the various

strategy segments against their respective standard deviation produces positive coefficients which are

statistically insignificant. Investors in the segment Technical Analysis Mix earn the lowest returns, but

18

they also bear the second lowest risk. On the other side of the coin, investors in the segment Intuition

bear the most risk, and earn the third lowest returns.

We note that the relationship between ambition and strategy selection is stronger than the

relationship between risk appetite and strategy selection. Interestingly, the use of fundamental

analysis and technical analysis increases with ambition, whereas intuition decreases (Figure 14).

6. Summary and Conclusions

Using recent matched survey/trading data of a large sample of individual online investors we analyze

how systematic differences in investors’ psychological profiles in terms of their traits, objectives, and

strategies impact their portfolios and returns. Our results extend the literature on the impact of

overconfidence, competence, entertainment/gambling, and risk appetite on individual investor

behavior. Below we highlight our findings, beginning with the impact of objectives on performance.

Investors whose primary objective is speculation earn considerably lower returns and bear much

more risk than investors with other objectives. Notably, capital growth is the most prominent investor

objective, followed by entertainment (hobby), and speculating.

The strategies investors employ reflect their sophistication and experience more than their

objectives. Our data indicate that online investors rely on their own intuition more frequently than any

other strategy. Our findings suggest that the addition of financial news and professional advice to

intuition leads to portfolios featuring more securities and greater turnover. Interestingly, investors

who combine intuition and financial news earn higher returns and incur higher risk than investors who

rely on intuition alone.

Reliance on intuition declines with sophistication, while the use of technical analysis and

fundamental analysis increase with sophistication. Our results indicate that technical analysis is

negatively associated with returns, even before accounting for transaction costs. In contrast,

fundamental analysis is positively associated with returns on both a gross and net basis, and with the

number of stocks held.

Investor traits and behavioral phenomena independently impact portfolio turnover, performance,

and risk. Turnover is positively related to risk appetite and ambition, and negatively related to

experience. Gross return is positively related to risk appetite, but negatively related to experience.

Portfolio return standard deviation is positively related to risk appetite, ambition, and experience. Our

findings are consistent with the notion that overconfidence effects are manifest within length of

investment experience and choice of strategies, especially technical analysis. We also suggest that

perceived competence reflects familiarity bias, and is manifest in the degree to which investors rely

on financial news, advice from brokers, and use fundamental analysis. Finally, whereas the literature

combines entertainment and gambling as objectives, we find that the psychological profiles of

speculators and hobbyists are quite different from each other. To their detriment, speculators are much

more ambitious and view themselves as much more sophisticated than hobbyists.

19

References

Bailey, W., A. Kumar, and D. Ng (2010), "Behavioral Biases of Mutual Fund Investors," Journal of

Financial Economics

, Forthcoming.

Barber, B. M. and T. Odean (2000), "Trading is Hazardous to Your Wealth: the Common Stock

Investment Performance of Individual Investors," The Journal of Finance, 55(2), 773-806.

Barber, B. M. and T. Odean (2001a), "Boys Will be Boys: Gender, Overconfidence, and Common

Stock Investment," The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 1 261-92.

Barber, B. M. and T. Odean (2001b), "The Internet and the Investor," Journal of Economic

Perspectives

, 15(1), 41-54.

Barber, B. M. and T. Odean (2002), "Online Investors: Do the Slow Die First?," Review of Financial

Studies

, 15(2), 455-87.

Bauer, R., M. Cosemans, and P. M. A. Eichholtz (2009), "Option Trading and Individual Investor

Performance," Journal of Banking and Finance, 33(4), 731-46.

Carhart, M (1997), "On Persistence in Mutual Fund Performance," The Journal of Finance, 52 57-82.

Dhar, R. and N. Zhu (2006), "Up Close and Personal: Investor Sophistication and the Disposition

Effect," Management Science, 52(5), 726-40.

Dorn, D. and G. Huberman (2005), "Talk and Action: What Individual Investors Say and What They

Do," Review of Finance, 9 437-81.

Dorn, D. and G. Huberman (2009), "Preferred Risk Habitat of Individual Investors," Journal of

Financial Economics

, 97(1), 155-73.

Dorn, D. and P. Sengmueller (2009), "Trading as Entertainment?," Management Science, 55(4), 591-

603.

Gervais, S. and T. Odean (2001), "Learning to be Overconfident," Review of Financial Studies, 14(1),

1-27.

Glaser, M. and M. Weber (2007a), "Overconfidence and Trading Volume," The Geneva Risk and

Insurance Review

, 32(1), 36.

Glaser, M. and M. Weber (2007b), "Why Inexperienced Investors do not Learn: They do not Know

their past Portfolio Performance," Finance Research Letters, 4 203-16.

Goetzmann, W. N. and A. Kumar (2008), "Equity Portfolio Diversification," Review of Finance,

12(3), 433-63.

Graham, J. R., C. R. Harvey, and H. Huang (2009), "Investor Competence, Trading Frequency, and

Home Bias," Management Science, 55(7), 1094-106.

Grinblatt, M. and M. Keloharju (2009), "Sensation Seeking, Overconfidence, and Trading Activity,"

The Journal of Finance

, 64(2), 549-78.

Hair, J. F., R. E. Anderson, R. L. Tatham, and W. C. Black (1998), Multivariate Data Analysis. Upper

Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Kahneman, D. and D. Lovallo (1993), "Timid Choices and Bold Forecasts: A Cognitive Perspective

on Risk Taking," Management Science, 39(1), 17-31.

Kumar, A. (2009), "Who Gambles in the Stock Market?," The Journal of Finance, 64(4), 1889-933.

Markowitz, H. M. (1952), "The Utility of Wealth," Journal of Political Economy, 60(2), 151-8.

Seru, A., T. Shumway, and N. Stoffman (2010), "Learning by Trading," Review of Financial Studies,

23(2), 705-39.

Shefrin, H. and M. Statman (1995), "Making Sense of Beta, Size, and Book-to-Market," Journal of

Portfolio Management

, 21(2), 26-34.

Shefrin, H. and M. Statman (2000), "Behavioral Portfolio Theory," The Journal of Financial and

Quantitative Analysis

, 35(2), 127-51.

Slovic, P. and B. Corrigan (1973), "Behavioral Problems of Adhering to a Decision Policy," Talk

presented at The Institute for Quantitative Research in Finance, May 1, Napa, CA

.

Solt, M. E. and M. Statman (1989), "Good Companies, Bad Stocks," Journal of Portfolio

Management

, Summer.

Statman, M. (2002), "Lottery Players / Stock Traders," Financial Analysts Journal, 58(1), 14-21.

Statman, M. (2010), "Characteristics, Affect, and Stock Returns," working paper.

Statman, M. (2011), What Investors Really Want: Discover What Drives Investor Behavior and Make

Smarter Financial Decisions

. New York: McGraw-Hill.

20

Figure 1: Variables constructed from survey responses

Variables

Answer categories

Investment Objective

What is your most important investment objective with

the investment portfolio at this brokerage firm?

1 – Capital growth: achieve a higher expected

return than on a savings account

2 – Hobby: interest in stock market

3 – Saving for retirement: being able to stop

working on an earlier age

4 – Speculation: try to profit from short-term

developments on the stock market

5 – Building financial buffer: building a

financial buffer for future expenses

Investment Strategy

Which strategies do you use as a basis for your

investment decisions (multiple answers possible)?

1 – Financial news: I base my investment

decisions on financial news

2 – Intuition: I base my investment decisions on

my personal intuition

3 – Technical analysis: I base my investment

decisions on technical analysis

4 – Fundamental analysis: I base my investment

decisions on fundamental analysis

5 – Professional advice: I base my investment

decisions on the professional advice from an

investment advisor

6 – Tips from others: I base my investment

decisions on tips from others such as friends or

family.

7 – Other

Ambition Level

How ambitious do you consider yourself to be?

1 – I am not ambitious

2 – I am a bit ambitious

3 – I am moderately ambitious

4 – I am quite ambitious

5 – I am very ambitious

Risk Appetite

Investors answer a set of questions, measuring their

sensitivity for losses, time horizon, and subjective

probabilities of chance events. This leads to a risk

profile categorization between 1 and 7.

1 – Very Conservative

2 – Conservative

3 – Defensive

4 – Careful

5 – Offensive

6 – Speculative

7 – Very speculative

Investor Sophistication

What kind of investor do you consider yourself to be?

1 – A novice investor

2 – An advanced investor

3 – A very advanced investor

21

Figure 2: MSCI Netherlands January 2000 – March 2006

Figure 3: Investor age

0

200

400

600

800

1000

1200

1400

1600

1800

Jan-00

Jan-01

Jan-02

Jan-03

Jan-04

Jan-05

Jan-06

M

S

C

I

N

e

th

e

rl

a

n

d

s

In

d

e

x

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

30%

18-29

years

30-39

years

40-49

years

50-59

years

60-69

years

70-79

years

80-89

years

P

e

rc

e

n

t

Figure 4: Investor experience

Figure 5: Investor sophistication

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

30%

35%

0 - 1 year

1 - 3 years

3 - 5 years

5 - 10 years

> 10 years

P

e

r

c

e

n

t

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

novice investor

advanced investor

very advanced investor

P

e

rc

e

n

t

22

Figure 6: Investor risk appetite

Figure 7: Investor ambition level

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

30%

very

conservative

conservative

defensive

careful

offensive

speculative

very

speculative

P

e

rc

e

n

t

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

30%

35%

40%

45%

I am not

ambitious

I am a little

bit ambitious

I am

moderately

ambitious

I am

considerably

ambitious

I am very

ambitious

P

e

rc

e

n

t

Figure 8: Investor strategies

Figure 9: Investor objectives

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

own intuition

financial

news

technical

analysis

fundamental

analysis

professional

advice

tips from

others

other

P

e

rc

e

n

t

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

30%

35%

40%

45%

capital

growth

hobby

speculating

building

financial

buffer

saving for

retirement

no goal

P

e

rc

e

n

t

Note: as investors could select more than one strategy the columns add up to more than 100%.

23

Figure 10: Investor ambition levels for sophistication levels

Figure 11: Investor risk appetite for sophistication levels

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

30%

35%

40%

45%

novice investor

advanced

investor

very advanced

investor

P

e

rc

e

n

t

I am not ambitious

I am a little bit ambitious

I am moderately ambitious

I am considerably ambitious

I am very ambitious

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

30%

35%

40%

45%

50%

novice investor

advanced

investor

very advanced

investor

P

e

rc

e

n

t

very conservative

conservative

defensive

careful

offensive

speculative

very speculative

Figure 12: Investor sophistication level per objective

Figure 13: Investor strategies per sophistication level

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

saving for

retirement

hobby

building

financial

buffer

speculating

capital

growth

P

e

rc

e

n

t

novice investor

advanced investor

very advanced investor

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

novice investor

advanced

investor

very advanced

investor

P

e

rc

e

n

t

technical analysis

fundamental analysis

financial news

professonal advice

tips from others

intuition

Note: as investors could select more than one strategy the columns add up to more than 100% per level of sophistication.

24

Figure 14: Investor strategies conditional on ambition level

Figure 15: Investor experience conditional on sophistication level

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

30%

35%

40%

45%

I am not

ambitious

I am a little

bit

ambitious

I am

moderately

ambitious

I am

considerably

ambitious

I am very

ambitious

P

e

rc

e

n

t

technical analysis

fundamental analysis

financial news

professional advicer

tips fromothers

own intuition

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

novice investor

advanced investor

very advanced

investor

Sophistication

P

e

rc

e

n

t

0 - 1 years

1 - 3 years

3 - 5 years

5 - 10 years

Figure 16: Investor strategies distribution over segments

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

financial

news

financal news

and intuition

intuition

technical

analysis mix

fundamental

analysis mix

financial

news,

intuition, and

professional

advice

P

e

rc

e

n

t

technical analysis

fundamental analysis

financial news

advice from a professional adviser

tips from others

own intuition

Note: this table shows the strategy usage of investors within segments. For example, within the segment

Technical Analysis Mix

, the dominant strategy is technical analysis, while fundamental analysis is also used,

though to a substantially lesser extent, and tips from others even less.

25

Table 1: Descriptive statistics

This table presents descriptive statistics for a sample of 65,325 investor accounts at a Dutch online broker. We

split the sample into 5,500 investors who participated in our investor survey and 59,825 who did not. The

sample period is from January 2000 to March 2006. The variables are defined as follows: Gender refers to the

fraction of accounts hold by a male investor only. Age in 2006 is the age in years of the main account holder.

Trades is the total number of stock trades per account during the sample period. Turnover stocks is the average

of the value of all stock purchases and sales in a given month divided by the beginning-of-the-month account

value. Turnover derivatives is the average of the value of all options purchases and sales in a given month

divided by the beginning-of-the-month account value. Portfolio value is the average market value of all assets in

the investor’s portfolio. Experience is the number of months an investor has been trading. Number of stocks

held refers to the number of different stocks an investor has in portfolio at the end of the sample period. HHI

refers to the Herfindahl-Hirschmann Index value for an investors’ portfolio at the end of the sample period (the

HHI is defined as the sum of the squared portfolio weights of all assets. For the purpose of the HHI calculations,

mutual funds are assumed to consist of 100 equally-weighted, non-overlapping, positions). HHI* refers to the

normalized index: (H – (1/N)) / (1 – (1/N)). Comparing HHI with HHI* makes clear how different the value

from the index is from uniform weights. Monthly net returns is the average raw return per month corrected for

transaction costs. Risk appetite refers to the self-reported riskiness of investors’ portfolios (1=very conservative,

7=very speculative). The table shows for each variable the mean, median, and standard deviation, as well as 5

th

,

25

th

, 75

th

, and 95

th

percentile values. If there is a statistically significant difference between attribute means

reported for the two samples (survey respondents and non-respondents), it is noted by asterisks in the mean

columns of the non-respondent sample. The mean comparison tests allow for different variances within the two

groups. ***/**/* indicate that the means are significantly different at the 1%/5%/10% level.

A: 5,500 Respondents of the Investor Survey

Mean

Std. Dev

5th Pctl

25th Pctl Median

75th Pctl 95th Pctl

Gender (male =1)

0.58

Age in 2006 (years)

49.70

12.73

28.00

40.00

50.00

59.00

70.00

Trades (#)

76.45

132.00

1.00

9.00

30.00

83.00

311.00

Turnover stocks (%)

42.40

121.00

0.00

3.89

10.99

31.48

173.05

Turnover derivatives (%)

16.50

79.81

0.00

0.00

3.62

7.52

68.45

Portfolio value (€)

45,915

142,576

1,057

5,321

15,234

42,406

166,840

Experience (months)

40.21

20.91

9.00

22.00

39.00

60.00

72.00

Number of stocks held

6.57

7.39

1.00

2.00

4.00

8.00

20.00

HHI (%)

27.78

23.28

1.10

9.80

21.14

39.73

78.42

HHI* (%)

17.20

21.55

0.16

4.06

9.06

20.74

70.69

Monthly Net Returns

-0.003

0.059

-0.071

-0.010

0.003

0.010

0.041

Risk Appetite (1-7)

5.31

1.61

2.00

4.00

6.00

7.00

7.00

B: 59,825 Non-Respondents of the Investor Survey

Mean

Std. Dev

5th Pctl

25th Pctl Median