J Orthop Sci (2006) 11:333–341

DOI 10.1007/s00776-006-1021-1

Original article

Multicenter study for Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease in Japan

Wook-Cheol Kim

1

, Kazuo Hiroshima

2

, and Toshihiko Imaeda

3

1

Department of Orthopaedics, Graduate School of Medical Science, Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine, Kawaramachi-Hirokoji,

Kamigyou-ku, Kyoto 602-8566, Japan

2

Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, National Hospital Organization, Osaka National Hospital, Osaka, Japan

3

Department of Public Health, Fujita Health University School of Medicine, Aichi, Japan

Introduction

In Japan, as the number of newborn babies is gradually

decreasing, the incidence of pediatric orthopedic

disease decreases with time. Therefore, the Japanese

Pediatric Orthopaedic Association (JPOA) created a

project team in 2000 to research pediatric orthopedic

disease through a multicenter study. The aim of this

study was to collect epidemiological data on Legg-

Calvé-Perthes disease (LCPD), investigate what treat-

ments for LCPD had been conducted, and the outcomes

of these treatment methods. Using multiple logistic

regression, the risk factors affecting the prognosis of

LCPD were determined.

Material and methods

A survey was sent to approximately 2000 hospitals and

children’s institutions that had been authorized by the

Japanese Orthopaedic Association (JOA). The follow-

ing data were collected for each patient known to have

a diagnosis of LCPD: age, sex, date of diagnosis, family

history, sports history, affected sites, symptoms, loca-

tion of pain, Catterall

1

classification and date of classifi-

cation, Herring

2

classification and date of classification,

date of treatment initiation, treatment methods used

(including whether containment or noncontainment

methods had been used and whether weight-bearing or

non-weight-bearing methods were used if conservative

containment methods had been performed), bracing

period, Stulberg

3

classification and date of evaluation,

and age at last follow-up. The patients in this series were

<

15 years old and were diagnosed as having LCPD dur-

ing January 1, 1993 to December 31, 1995.

In the collected data analysis, one of every two pa-

tients had the same name and same birthday and so was

excluded. For the evaluation of outcome, patients who

had had a hormonal disorder, genetic disorder, and

Abstract

Background. The Japanese Pediatric Orthopaedic Associa-

tion created a project team in 2000 to research pediatric ortho-

pedic disease through a multicenter study. The aim of this

study was to collect epidemiological data on Legg-Calvé-

Perthes disease (LCPD) in Japan.

Methods. The following data were collected by a survey: age,

sex, date of diagnosis, family history, sports history, affected

sites, symptoms, location of pain, Catterall classification,

Herring classification, date of treatment initiation, treatment

methods, bracing period, and Stulberg classification.

Results. A total of 711 patients with 766 affected hips were

seen from January 1, 1993 to December 31, 1995. The average

annual incidence of LCPD was 0.9/100 000. The average age

at diagnosis was 7 years 1 month (2.3–14.3 years). The male/

female ratio of the study population was 6.3 : 1.0. The affected-

side ratio (right hip/left hip/both hips) was 5.1 : 6.8 : 1.0. Both

hips were affected in 7.7% of this series. By the Stulberg

classification there were 211 (69.4%) type I and II patients

(of 304 total patients). Six treatment methods for unilateral

LCPD were compared, and there were no significant differ-

ences in outcome among the six groups. The ordinal logistic

regression analysis showed that the Herring classification, age

at the time of diagnosis, and the affected side (for unilateral

LCPD) were significant predictors. The ordinal logistic regres-

sion analysis also showed that operative treatment had a bet-

ter outcome than conservative treatment, with an odds ratio of

1.872.

Conclusions. Many containment methods for LCPD have

been performed in Japan, and the optimal treatment method

for LCPD was not determined in this study. The overall out-

come, however, was not worse than that in worldwide reports.

Offprint requests to: W.-C. Kim

Received: June 18, 2005 / Accepted: March 9, 2006

334

W.-C. Kim et al.: Multicenter study of Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease

congenital hip disorder were excluded. For the compari-

son of treatment methods, patients who had no Stulberg

evaluation and bilateral LCPD were excluded. Patients

evaluated by the Stulberg classification who were

>

13

years of age or those followed up more than 3.5 years

after diagnosis of LCPD were included in a group to

compare outcomes among treatment methods.

For statistical analysis, the Kruskal-Wallis H test was

used to compare outcomes among treatment methods.

An ordinal logistic regression analysis was used to pre-

dict the outcomes evaluated by the Stulberg classifica-

tion. The ordinal logistic regression analysis was utilized

for 294 of 304 patients who had data consisting of age

at diagnosis, sex, affected side, Herring classification

and the time of classification after onset, treatment

methods [operative methods: Salter innominate

osteotomy (SIO), femoral varus osteotomy (FVO);

conservative methods: bilateral abduction with full

weight-bearing (BFW), bilateral abduction with

non-weight-bearing (BNW), hemiabduction with full

weight-bearing (HFW), hemiabduction with partial

weight-bearing (HPW), and hemiabduction with

non-weight-bearing (HNW)], follow-up period, and

Stulberg evaluation. In the ordinal logistic regression

analysis, the Stulberg evaluation was set as a predictor

(dependent variable), and the other data were defined

as independent factors or covariates. The odds ratio was

expressed by a ordinal number as exp(B); for example,

for the risk ratio of sex (female/male: female as a

numerator and male as a denominator), exp(B)

=

1.5

means that females have a prognosis that is 1.5 times

worse than that of males. All statistical analyses were

conducted using the statistical package of Social Science

(SPSS) version 12.0J software. The critical values for

significance were set at P

<

0.05.

Results

Altogether, 95 institutions and hospitals, including all

of the children’s hospitals and university hospitals, en-

gaged in pediatric orthopedics in Japan responded to

the survey. There were a total of 711 patients with 766

affected hips. A total of 217 patients were affected in

1993, 266 in 1994, and 228 in 1995 (Table 1), with 606

male and 95 female patients. The average age at diagno-

sis was 7 years 1 month (2.3–14.3 years). A total of 281

right hips were affected, 372 left hips, and 55 cases of

both hips (7.7%). A total of 38 patients had associated

complications or disorders: 6 had hormonal disease (4

hypothalamic dwarfism, 2 hypothyroidism), 2 had short

status (

<

2 SD), 1 had scoliosis, 1 had hemihypertrophy,

3 had DDH, 1 had club foot, 1 had MED, 1 had a

habitual patellar dislocation, 13 had an allergic disorder,

3 had congenital heart disease, 2 had a genetic disorder,

1 had mental retardation, 1 had femoral lateral condylar

osteonecrosis, 1 had an auditory disorder, 1 had a

squint, and 1 infant had low body weight. Pain was the

chief problem in 92%, hip joint pain in 56%, knee joint

pain in 12.5%, thigh pain in 9.2% and no pain in 8%.

Gait pain (83.3%) and limping gait (96%) were also

symptoms (Table 2). There was a positive family history

in 4.5% of patients, with 50% of these patients having

an affected sibling (Table 3). There was a positive sports

history in 14.2% of the patients (Table 3).

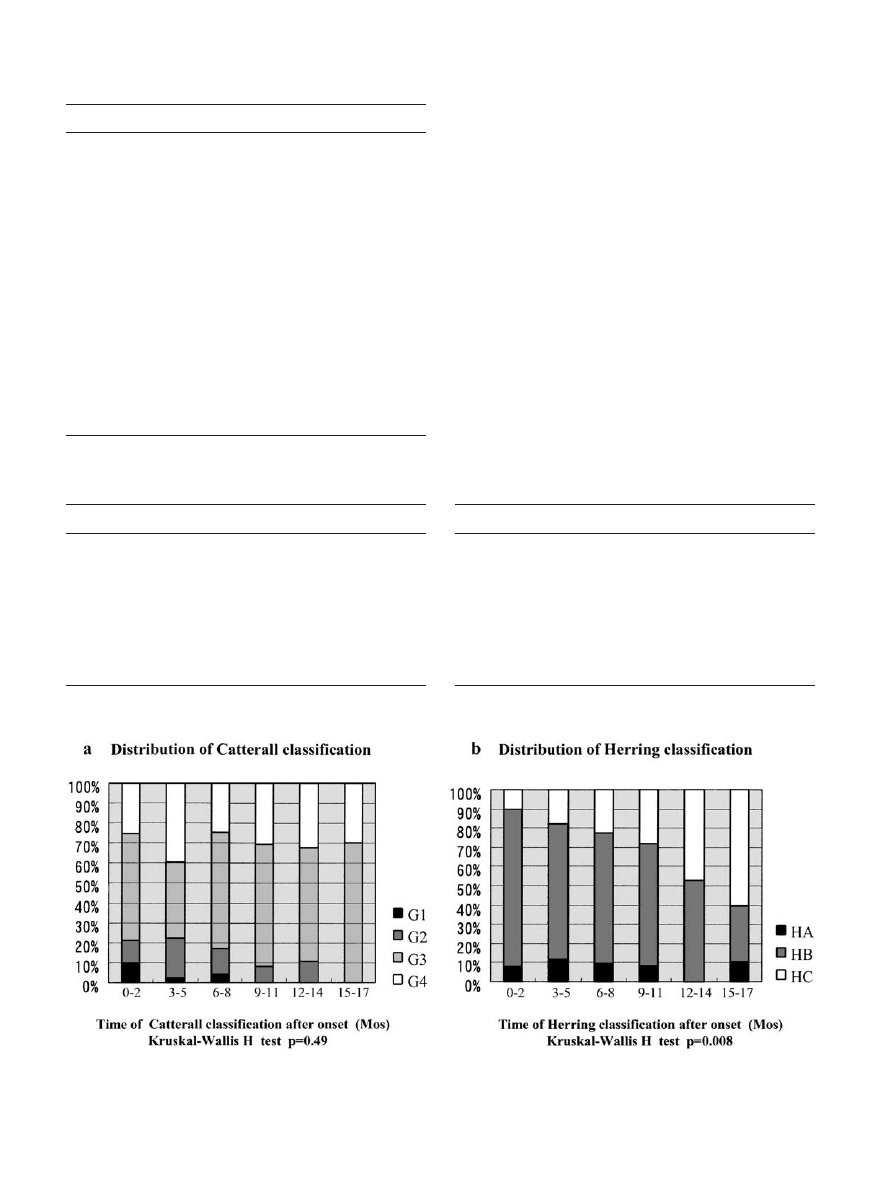

Using the Catterall classification, 50.6% of the pa-

tients were classified as group 3 and 30.2% as group 4

(Table 4). There was no significant correlation between

the distribution of the Catterall classification and the

time of classification after onset (Fig. 1a). In the Herring

Table 1. Incidence of LCPD from 1993 to 1995 in Japan

LCPD

Population (

<

15 ages)

Incidence (/10

5

)

Year

M/F/total

M/F/total (

×

10

6

)

M/F/total

1993

190/27/217

13.7/13.0/26.7

1.39/0.21/0.81

1994

230/36/266

13.5/12.3/25.8

1.70/0.29/1.03

1995

199/29/228

13.6/12.6/26.2

1.46/0.23/0.87

Average

1.51/0.24/0.90

LCPD, Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease; M, males; F, females

Table 2. Symptoms of LCPD

Symptom

No. of patients

No pain

58/695 (8%)

Pain

637/ 695 (92%)

Hip

359

Knee

80

Thigh

59

Hip and knee

44

Hip and thigh

42

Thigh and knee

15

Hip, thigh, and knee

11

Leg or foot

9

Others

8

Gait pain

443/532 (83.3%)

Limping gaits

626/652 (96.0%)

335

W.-C. Kim et al.: Multicenter study of Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease

classification, 60.9% of patients were type B and 27.3%

type C (Table 4). There was a significant correlation

between the distribution by the Herring classification

and the time of classification after onset (Kruskal-

Wallis H test: P

=

0.008) (Fig. 1b). Containment therapy

(447 abduction bracing, 17 Salter innominate oste-

otomy, 74 femoral varus osteotomy, 3 triple osteotomy,

among others) was performed in 632 (92.5%) of the

684 responding cases. Noncontainment therapy (3 non-

weight-bearing methods, 11 no abduction bracing after

limb traction, 4 no abduction bracing after sling, 3

restriction of physical exercise, 5 femoral valgus oste-

otomy, 4 anterior rotational osteotomy of the femoral

neck, 1 Chiari osteotomy, 1 vascularized bone graft

after biopsy, 2 trochanteric advancement) was utilized

for 35 patients (5.1%). A total of 16 (2.3%) patients

were kept under observation only and did not receive

any treatment (Table 5).

To compare the outcomes, 304 of 611 patients who

had been evaluated by the Stulberg classification were

Table 4. Catterall and Herring classifications

Parameter

No.

Catterall classification

Group 1 (G1)

30 (4.3%)

Group 2 (G2)

103 (14.8%)

Group 3 (G3)

352 (50.6%)

Group 4 (G4)

210 (30.2%)

Herring classification

Type A (HA)

68 (11.8%)

Type B (HB)

350 (60.9%)

Type C (HC)

157 (27.3%)

Table 3. Family and sports history

Historical factor

No.

Family history

Negative

530 (95.5%)

Positive

25 (4.5%)

Siblings

12

Father

7

Others

2

No response

4

No response

10

Sports history

Not engaged

350 (85.8%)

Engaged

58 (14.2%)

Soccer

27

Baseball

10

Gymnastics

4

Field athletics

4

Swimming

3

Others

7

No response

2

No response

303

Fig. 1. a Catterall classification and the time of classification. b Herring classification and the time of classification

Table 5. Treatment methods for LCPD in Japan

Treatment

No.

Containment methods

632/683 (92.5%)

Conservative

519 (82.1%)

Operative

113 (17.9%)

Noncontainment methods

35/683 (5.1%)

Conservative

25 (71.4%)

Operative

10 (28.6%)

Observation

16/683 (2.3%)

No response

28

Total

711

336

W.-C. Kim et al.: Multicenter study of Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease

selected; they had been classified when

>

13 years of age

or had been followed up for more than 3.5 years after

their diagnosis of LCPD. Of the 304 patients, 76 (25%)

were Stulberg type I, 135 (44%) were type II, 69 (23%)

were type III, 21 (7%) were type IV, and 3 (1%) were

type V (Table 6). Altogether, 96.7% of Herring type A

patients were Stulberg type I or II (100% of Catterall

group 1 and 93.5% of Catterall group 2). Therefore, to

compare the outcomes of the seven treatment methods,

Catterall groups 1 and 2 and Herring type A patients

were excluded from the younger-group and the older-

group analyses (Tables 7, 8). However, there was no

significant difference among the six treatment methods

(HFW was excluded because of the small number of

subjects) in either the younger group or older group in

the Kruskal-Wallis H test.

An ordinal logistic regression analysis showed that

the Herring classification was the highest predictor; the

odds ratios for A/C and B/C were 0.030 and 0.170,

respectively. The age at the time of diagnosis of LCPD

was the next predictor, with an odds ratio of 1.445 by 1

year. The right hip joint showed a worse prognosis than

the left hip joint, with an odds ratio of 1.577. There was

a significant difference between conservative treatment

methods and operative methods, with an odds ratio of

1.872 (Table 9). There was no significant correlation

with outcome among conservative treatment methods

(BFW, BNW, HFW, HPW, HNW) (Table 10). There

was also no significant difference in the outcomes be-

tween the SIO and FVO (Table 11).

Discussion

Epidemiological data

There has been no previous epidemiological study of

LCPD in Japan. The number of patients with LCPD in

1993 was 217 (190 boys, 27 girls), 266 (230 boys, 36 girls)

in 1994, and 228 (199 boys, 29 girls) in 1995. The popu-

lation of children

<

15 years of age was 26.7 million in

1993, 25.8 million in 1994, and 26.2 in 1995 from the

tables of trends in population by sex and age of the

Japanese National Government Survey; the incidence

of LCPD was 0.81/100 000 in 1993, 1.03/100 000 in 1994,

and 0.87/100 000 in 1995 (Table 1). The average annual

incidence of LCPD was 0.9/100 000. The number of

LCPD patients in Japan was less than that of white

children previously reported

4–7

(Table 12). The

incidence was dependent on gender, race, country, and

Table 6. Outcome of 304 patients evaluated by Stulberg classification who had been

classified when

>

13 years of age or followed up for

>

3.5 years after LCPD diagnosis

Parameter

No.

Stulberg evaluation: classification time after onset (months)

12.0

±

2.2

a

I

76 (25%)

b

II

69 (23%)

III

135 (44%)

IV

21 (7%)

V

3 (1%)

Subjects of unilateral LCPD

Age at diagnosis (years)

7.0

±

2.1

a

Sex (no. of patients)

Male

270

Female

34

Affected side (no. of patients)

Right

140

Left

164

Follow-up periods (years)

5.0

±

1.0

a

Radiographic classification

Catterall classification (time after onset, months)

6.9

±

4.2

a

I

10

c

II

39

III

164

IV

91

Herring classification (time after onset, months)

6.6

±

3.9

a

A

30

c

B

204

C

70

a

Average

±

SD

b

Number and percent of patients

c

Number of patients

337

W.-C. Kim et al.: Multicenter study of Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease

Table 7.

Outcomes of patients

<

8 years old (minus patients of Catterall groups 1 and 2 and Herring type A) (

n

=

173)

Age

Sex

Side

CaT

Catterall

HeT

Herring

OpT

BrP

StT

Stulberg classification

FU

Outcome

(years)

a

(M/F)

(Rt/Lt)

(months)

a

III

IV

(months)

a

BC

(months)

a

(months)

a

(years)

a

II

I

III

IV

V

(years)

a

SIO (

n

=

9)

6.7

±

0.8

9/0

6/3

8.0

±

3.5

7

2

8.0

±

3.5

5

4

5.1

±

2.4

—

12.5

±

1.4

3

5

1

0

0

5.8

±

1.0

FVO (

n

=

24)

6.4

±

1.2

21/3

14/10

4.0

±

3.3

11

13

4.3

±

3.7

15

9

5.6

±

3.4

—

11.5

±

1.3

8

6

7

3

0

5.1

±

0.8

HNW (

n

=

40)

6.0

±

1.5

39/1

21/19

8.8

±

4.1

26

14

8.2

±

3.3

30

10

—

19.3

±

7.0

11.0

±

2.1

9

2

2

5

4

0

5.0

±

0.8

HPW (

n

=

12)

6.1

±

1.3

10/2

3/9

6.3

±

3.5

9

3

6.4

±

3.4

8

4

—

12.9

±

4.3

11.8

±

2.1

4

2

5

0

0

5.8

±

1.2

BNW (

n

=

59)

6.0

±

1.3

52/7

30/29

7.4

±

4.0

31

28

7.0

±

3.9

46

13

—

17.5

±

7.3

11.0

±

1.5

12

31

11

5

0

5.0

±

0.8

BFW (

n

=

29)

5.5

±

1.4

27/2

18/24

8.0

±

4.9

17

12

7.5

±

4.5

14

15

—

17.0

±

7.3

10.9

±

1.9

4

1

0

1

3

2

0

5.3

±

1.2

SIO, Salter innominate osteotomy; FVO, femoral varus osteotomy; HNW, hemi non-weight-bearing brace; HPW, hemi partial-weight-be

aring brace; HFW, hemi full-weight-bearing brace;

BNW, bilateral non-weight-bearing brace; BFW, bilateral full-weight-bearing brace; CaT, time of Catterall classification; HeT, t

ime of Herring classification; OpT, time of operation; BrP,

bracing periods; StT, time of Stulberg evaluation; FU, follow-up period

a

Results are the average

±

SD

NS, Kruskal-Wallis H test

Table 8.

Outcomes of LCPD patients

≥

8 years old (minus patients of Catterall groups 1 and 2 and Herring type A) (

n

=

65)

Age

Sex

Side

CaT

Catterall

HeT

Herring

OpT

BrP

StT

Stulberg classification

FU

Outcome

(years)

a

(M/F)

(Rt/Lt)

(months)

a

III

IV

(months)

a

BC

(months)

a

(months)

a

(years)

a

II

I

III

IV

V

(years)

a

SIO (

n

=

4)

10.0

±

1.8

3/1

1/3

12.0

±

3.7

3

1

12.0

±

3.7

2

2

4.3

±

1.3

—

15.0

±

1.7

0

1

2

0

0

4.8

±

0.7

FVO (

n

=

14)

9.8

±

1.1

13/1

5/9

4.3

±

3.7

11

3

4.4

±

3.7

12

2

4.3

±

3.3

—

14.5

±

1.5

3

7

2

1

1

4.7

±

0.7

HNW (

n

=

11)

9.6

±

1.2

10/1

4/7

7.5

±

3.4

9

2

7.5

±

3.0

10

1

—

24.4

±

10.8

14.5

±

1.8

1

3

4

1

2

4.8

±

0.9

HPW (

n

=

3)

9.1

±

1.2

3/0

1/2

7.7

±

1.5

2

1

12.0

±

3.6

1

2

—

15.7

±

5.1

13.9

±

1.1

0

0

2

1

0

4.8

±

1.4

BNW (

n

=

29)

9.4

±

1.6

26/3

11/18

6.9

±

4.0

21

8

6.6

±

3.7

27

2

—

16.2

±

5.5

14.0

±

1.8

1

1

6

1

0

2

0

4.6

±

0.8

BFW (

n

=

4)

9.7

±

1.5

4/0

2/2

7.5

±

3.3

3

1

6.5

±

1.7

2

2

—

12.3

±

1.7

15.0

±

2.2

0

2

1

1

0

5.4

±

1.0

a

Results are the average

±

SD

NS, Kruskal-Wallis H test

338

W.-C. Kim et al.: Multicenter study of Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease

Table 11. Ordinal logistic regression analysis: operative cases (n

=

57)

95% CI for Exp(B)

Factor

B

SE

Wald

Lower

Exp(B)

Upper

Age at diagnosis (years)

0.350

0.150

5.467*

1.058

1.419

1.902

Sex (female/male)

0.134

0.883

0.023

0.202

1.144

6.458

Affected side (Rt/Lt)

−

0.033

0.507

0.004

0.358

0.967

2.614

Time of Herring evaluation (months)

−

0.034

0.089

1.073

0.921

1.096

1.304

Herring type

A/C

−

2.865

1.452

3.895*

0.003

0.057

0.980

B/C

−

1.497

0.691

4.694*

0.058

0.224

0.867

Treatment method (FVO/SIO)

0.806

0.727

1.227

0.538

2.238

9.313

Follow-up period (years)

0.205

0.272

0.645

0.730

1.245

2.123

Property of model: parallel line test: by the null hypothesis the

−

2 exponential likelihood is 132.097. By the general hypothesis it is 111.241

(

χ

2

=

20.838; df

=

24; P

=

0.648)

* P

<

0.05

Table 10. Ordinal logistic regression analysis: conservative cases (n

=

237)

95% CI for Exp(B)

Factor

B

SE

Wald

Lower

Exp(B)

Upper

Age at diagnosis (years)

0.389

0.067

34.02***

1.295

1.475

1.681

Sex (F/M)

0.307

0.401

0.588

0.620

1.360

2.983

Affected side (Rt/Lt)

0.590

0.262

5.071*

1.079

1.803

3.012

Time of Herring evaluation (months)

−

0.072

0.035

4.204

0.868

0.930

0.997

Herring type

A/C

−

3.623

0.587

38.12***

0.008

0.027

0.084

B/C

−

1.672

0.359

21.70***

0.093

0.188

0.380

Treatment method

BFW/HPF

0.800

0.538

2.215

0.779

2.226

6.386

BNW/HPF

0.449

0.505

0.791

0.582

1.567

4.220

HFW/HPF

−

0.856

0.945

0.819

0.067

0.425

2.711

HNW/HPF

0.425

0.543

0.612

0.528

1.530

4.434

Bracing periods (months)

0.028

0.020

1.949

0.989

1.028

1.069

Follow-up period (years)

0.209

0.137

2.335

0.943

1.233

1.613

Property of model (paralell line test): by the null hypothesis the

−

2 exponential likelihood is 507.902. By the general hypothesis, the

−

2

exponential likelihood is 490.026 (

χ

2

=

17.873; df

=

36; P

=

0.995)

* P

<

0.05; ** P

<

0.01; *** P

<

0.001

Table 9. Ordinal logistic regression analysis: all cases (n

=

294)

95% CI for Exp(B)

Factor

B

SE

Wald

Lower

Exp(B)

Upper

Age at diagnosis (years)

0.368

0.059

39.23***

1.288

1.445

1.621

Sex (female/male)

0.282

0.355

0.628

0.661

1.325

2.658

Affected side (Rt/Lt)

0.455

0.226

4.071*

1.013

1.577

2.454

Time of Herring evaluation (months)

−

0.034

0.031

1.202

0.910

0.967

1.027

Herring type

A/C

−

3.498

0.526

44.30***

0.011

0.030

0.085

B/C

−

1.774

0.305

33.74***

0.093

0.170

0.309

Treatment method Con/Ope

0.627

0.296

4.502*

1.049

1.872

3.341

Follow-up period (years)

0.205

0.119

2.971

0.972

1.228

1.550

Property of model (parallel line test): by the null hypothesis the

−

2 exponential likelihood is 651.788. By the general hypothesis, the

−

2

exponential likelihood is 640.648 (

χ

2

=

11.140; df

=

24; P

=

0.988)

SE, standard error; 95% CI, 95% of confidence interval; Exp(B), exponential B

=

Odds ratio

* P

<

0.05; ** P

<

0.01; *** P

<

0.001

339

W.-C. Kim et al.: Multicenter study of Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease

Table 12. Incidence of LCPD

Incidence

Year

Study

Location

Males

Females

Total (/10

5

)

1966

Molloy

4

Massachusetts, USA

0.57

1972

Gray

5

British Columbia, Canada

8.4

1.6

5.1

1983

Hall

6

Liverpool, England

25.8

4.9

15.6

1992

Moberg

7

Uppsala, Sweden

8.5

2.1

6.3

2005

Multicenter study in Japan

1.51

0.24

0.9

economic situation.

6

As for incidence, the white races

had a higher incidence than the yellow races, and the

yellow races were higher than the black races.

6

Bilateral

hips were affected in 7.7% of this series. In 1978,

Wynne-Davies and Gormley

8

reported the incidence of

bilateral LCPD to be 11.3% among Edinburgh and

Glasgow patients. If the research period had been

longer than 3 years, the incidence of bilateral LCPD

might have increased.

The symptoms of LCPD were pain, gait pain, and

limping gait. Pain located only in the hip joint was re-

ported in 56.4% of patients, only in the knee joint in

12.5%, and only in the thigh in 9%. In total, 92.0% of

patients complained of pain, with 8% having no pain.

Special attention should be paid to the group of patients

who did not have any pain at the time of the initial

consultation (Table 2). Patients with a history of gait

pain comprised 83.3% of the total number, and 96.0%

of the patients had a history of limping gait.

The genetic problems described were also found in

siblings, twins, cousins, father, or uncles with skeletal

problems. Wynne-Davies and Gormley

8

reported an

incidence of LCPD of 1.0% among first-degree rela-

tives, 0.3% among second-degree relatives, and 0.3%

among third-degree relatives. The family history was

positive in 4.5% of this series. It was thought that a

lower incidence of a positive family history as well as the

incidence of LCPD depended on the factor of race

(Asian people).

Herring type B was a major type of radiographic

classification, accounting for more than 60% in this

series. Recently, Herring et al.

9

tried to use type B/C a

modified lateral pillar classification to provide a more

precise classification for prognostic evaluation. We

could not use the modified lateral pillar classification in

this study because the study started prior to Herring

et al.’s report. The optimal time for applying the Her-

ring classification was more than 7 months after the

onset because the decreasing rate of lateral pillar height

plateaued 7 months later.

10

However, the distribution

of Herring types significantly depended on the time

of classification after onset of LCPD in this study

(Kruskal-Wallis H test: P

=

0.008) (Fig. 1b). This was

reasonable because the Herring types indicated that the

height of the lateral pillar had gradually decreased

with time after the onset of LCPD. The Catterall

classification had no significant correlation between the

Catterall groups and the time of classification after the

onset of LCPD because there was change in the necrotic

area, which does not depend on the time after onset

(Fig. 1a). However, the Catterall classification was

difficult to perform because it requires two-plane radio-

graphic assessment, which had been changed by the

deformity of the residual bone.

Treatment methods in Japan

Since Legg, Calvé, and Perthes first described the

pathological condition of LCPD in 1910, the main treat-

ment methods have been long bed rest and traction

of the affected limb, as reported by Danforth

11

and

Sundt.

12

There were many problems associated with

prolonged bed rest, and hence ambulatory treatments

using a non-weight-bearing technique were applied. In

1958, Evans and Lloyd-Roberts

13

reported that the out-

come of the Snyder

14

sling for LCPD was the same as

that of bed rest. In 1966, Harrison

15

reported the useful-

ness of containment methods that had been previously

advocated by Parker in 1929. The use of containment

methods then spread throughout the world. In Japan,

many treatment methods have been applied for LCPD,

including bilateral abduction casts or a brace, using

bilateral abduction braces such as the Newington

brace,

16

the Atlanta brace (Scottish-Rite),

17

the Bach-

elor (Toronto), and the modified abduction cast

(A-cast).

18–20

However, all of these patients were forced

into long periods of hospitalization in institutions.

Nowadays, many ambulatory orthoses for outpatients

have been tried. Patients with these braces are able to

go to school and attend the hospital as outpatients only.

Of this group, the Tachdjian brace,

21

the Nishino abduc-

tion brace,

22

the modified pogo-stick brace,

23,24

and the

SPOC (Shiga Pediatric Orthopaedic Centre) brace

25

are

currently popular in Japan. However, noncontainment

methods such as traction, non-weight-bearing, and

prolonged bed rest are still in use in some institutions.

Operative methods include varus osteotomy, Salter in-

nominate osteotomy, triple osteotomy, femoral valgus

340

W.-C. Kim et al.: Multicenter study of Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease

osteotomy, femoral neck rotational osteotomy, Chiari

osteotomy, vascularized bone graft, and great tro-

chanteric advancement. A total of 519 (82.1%) of 632

patients with LCPD were treated by conservative con-

tainment methods (HFW, HPW, HNW, BFW, BNW),

and 113 (17.9%) of 632 patients with LCPD were

treated by operative containment methods (SIO and

FVO) during this period in Japan.

Treatment methods and outcomes of unilateral LCPD

In 1986, Cooperman and Stulberg

26

reported the out-

comes of 248 cases treated by non-weight-bearing with

crutches, an Atlanta brace, a Newington abduction or-

thosis, and varus osteotomy of the femur. Stulberg types

I and II accounted for 50% of the non-weight-bearing

patient group, 64% of the Atlanta brace group, 71% of

the Newington abduction orthosis group, and 70% for

the varus osteotomy group. In 1995, Wang et al.

27

re-

ported that “good” and “fair” outcomes, as evaluated

by Mose’s

28

methods, were found in 49% of non-weight-

bearing with physical exercise patients, 49% of Atlanta

brace patients, 62% of Petrie cast patients 60% of varus

osteotomy patients, and 60% of Salter innominate

osteotomy patients.

18

A study by Grzegorzewski et al.

29

analyzed 142 cases, of which Stulberg types I and II

comprised 61 (80%) of 76 of the long-term rest and limb

traction management group, 15 (71%) of 21 of the

Petrie cast group, 53 (74%) of 74 the abduction orthosis

group, and 19 (73%) of 26 in the varus osteotomy

group. Grzegorzewski et al. reported that no significant

difference was found among the groups.

All of these studies concluded that there was no

significant difference in outcome among the treatment

methods for LCPD. The studies, however, cited many

factors related to the outcomes of LCPD. Herring et al.

noted that the lateral pillar classification and the age at

the onset of LCPD were highly and strongly correlated

with the outcomes evaluated by the Stulberg classifica-

tion.

30

Therefore, in this study the subjects were divided

into a young group and an older group to avoid the age

effect on the outcomes of the seven treatment methods.

In the

<

8 years old group, Stulberg type I and II ac-

counted for 8 (89%) of 9 patients treated by SIO, 14

(58%) of 24 patients treated by FVO, 31 (78%) of 40

patients treated by HNW (modified pogo-stick, Nishio,

Tachdjian), 6 (55%) of 11 patients treated by HPW

(SPOC), 43 (73%) of 59 patients treated by BNW (A-

cast, modified A-cast, Bachelor brace), and 14 (48%) of

29 patients treated by BFW (Toronto, Atlanta, A-cast

brace) (Table 7). In the

≥

8 years old group, Stulberg

types I and II accounted for 1 (33%) of 3 patients

treated by SIO, 10 (71%) of 14 patients treated by FVO,

4 (36%) of 11 patients treated by HNW, 0 of 3 patients

treated by HPW, 17 (59%) of 29 patients treated by

BNW, and 2 (50%) of 4 patients treated by BFW (Table

8). In the

<

8 years old group, SIO, HNW, and BNW had

good outcomes compared to other treatment methods

(Table 7). In the older group, FVO had the best out-

come compared to other treatment methods (Table 8).

For the older patients FVO showed better outcome

than SIO, and SIO seemed to have better outcome than

FVO in the young group. It was thought that SIO had

better coverage of the femoral head in the young group

than in the older group. However, there was no signifi-

cant difference between SIO and FVO because of the

small numbers in each group (Kruskal-Wallis H test).

Odds ratios by ordinal logistic regression for

unilateral LCPD

Many factors have been thought to relate to the progno-

sis of LCPD. The ordinal logistic regression analysis

showed that Herring classification, age at diagnosis, and

the side affected were significantly correlated with the

outcome (Table 9). It had not been reported previously

that the left hip joint in LCPD had a better prognosis

than the right hip joint. It is possible that the dominant

side of the lower extremity affected the outcome.

The operative methods (SIO and FVO) for LCPD gave

a significantly better prognosis than the conservative

methods (BFW, BNW, HFW, HPW, HNW), with an

odds ratio of 1.87 (P

=

0.034). However, with con-

servative treatment, there was no significant correlation

among the five treatment methods (Table 10). For

operative treatment, there was no significant difference

between SIO and FVO (Table 11). It was thought that

a larger number of subjects in each treatment group

is required for statistical significance. Many contain-

ment methods for LCPD have been performed in

Japan, and the optimal treatment method for LCPD

could not be determined in this study. The overall out-

come, however, was not worse than has been reported

worldwide.

Limitation of this study

In this series, we were unable to obtain the radiographic

assessment or the bone age at the time of LCPD diagno-

sis; nor did we have data on treatment delay, which

might affect the outcome. About one-third of the pa-

tients were skeletally mature at the time of the Stulberg

evaluation. Therefore, the outcomes of this series might

change after several years, and for this reason the pa-

tients should be followed up in the next multicenter

study for LCPD.

Acknowledgments. The members of the MCS committee of

JPOA thank the 95 children’s hospitals and institutions in

Japan for their collaboration.

341

W.-C. Kim et al.: Multicenter study of Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease

References

1. Catterall A. The natural history of Perthes’ disease. J Bone Joint

Surg Br 1971;53:37–53.

2. Herring JA, Neustadt JB, Williams JJ, Early JS, Browne RH.

The lateral pillar classification of Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease, J

Pediatr Orthop 1992;12:143–50.

3. Stulberg SD, Cooperman DR, Wallensten R. The natural history

of Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1981;63:

1095–108.

4. Molloy MK, MacMahon B. Incidence of Legg-Perthes disease

(osteochondritis deformance). N Engl J Med 1966;275:988–90.

5. Gray IM, Lowry RB, Renwick DH. Incidence and genetics of

Legg-Perthes disease (osteochondritis deformans) in British

Columbia: evidence of polygenic determination. J Med Genet

1972;9:197–202.

6. Hall AJ, Barker DJ, Dangerfield PH, Taylor JF. Perthes’ disease

of the hip in Liverpool. BMJ 1983;287:1757–9.

7. Moberg A, Rehnberg L. Incidence of Perthes’ disease in Uppsala,

Sweden. Acta Orthop Scand 1992;63:157–8.

8. Wynne-Davies R, Gormley J. The aetiology of Perthes’ disease:

genetic, epidemiological and growth factors in Edinburgh and

Glasgow patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1978;60:6–13.

9. Herring JA, Kim HT, Browne R. Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease,

Part I. Classification of radiographs with use of the modified

lateral pillar and Stulberg classifications. J Bone Joint Surg Am

2004;86:2103–18.

10. Lappin K, Kealey D, Cosgrove A. Herring classification: how

useful is the initial radiograph? J Pediatr Orthop 2002;22:479–82.

11. Danforth M. The treatment of Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease. J

Bone Joint Surg 1934;16:516–34.

12. Sundt H. Further investigation respecting mature coxae: Calvé-

Legg-Perthes disease with special regard to prognosis and treat-

ment. Acta Chir Scand Suppl 1949;148:1–101.

13. Evans DL, Lloyd-Roberts GC. Treatment in Legg-Calvé-Perthes’

disease: a comparison of in-patient and out-patient methods. J

Bone Joint Surg Br 1958;40:182–9.

14. Snyder CH. A sling for use in Legg-Perthes disease. J Bone Joint

Surg 1947;29:524–6.

15. Harrison MHM. Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease: the value of

roentgenographic measurement in clinical practice with special

reference to the Broomstick plaster method. J Bone Joint Surg

Am 1966;48:1301–18.

16. Martinez AG, Weinstein SL, Dietz FR. The weight-bearing ab-

duction brace for the treatment of Legg-Perthes disease. J Bone

Joint Surg Am 1992;74:12–21.

17. Meehan PL, Angel D, Nelson JM. The Scottish Rite abduction

orthosis for the treatment of Legg-Perthes disease: a radiographic

analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1992;74:2–12.

18. Petrie JG, Bitenc I. The abduction weight-bearing treatment in

Legg-Calvé-Perthes’ disease. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1971;53:54–62.

19. Tamura K, Inoue N, Ishioka T. Evaluation of modified A-cast in

the treatment of Legg-Calvé-Perthes’ disease. J Joint Surg 1985;4:

257–63 (in Japanese).

20. Tamura K, Futami T, Kobayasi M, Akiyama N. Long-term results

and its limitations of modified Petrie’ s cast. J Jpn Paediatr Orthop

Assoc 1993;3:157–62 (in Japanese).

21. Tachdjian MO, Jouett LD. Trilateral socket hip abduction

orthosis for the treatment of Legg-Perthes’ disease. Orthosis

Prosthetics 1968;22:49–62.

22. Kubota H, Noguchi Y, Nakashima Y, Suenaga E, Iwamoto Y.

Long-term follow up of conservative treatment (Nishio’s brace)

of Perthes’ disease. J Jpn Paediatr Orthop Assoc 2000;9:15–8 (in

Japanese).

23. Kim W-C, Kubo T, Hirasawa Y, Kusakabe T. Comparison be-

tween Tachdjian brace and modified pogo-stick brace for Perthes’

disease using Gait analysis. J Jpn Paediatr Orthop Assoc 1995;4:

275–9 (in Japanese).

24. Kim W-C, Hosokawa M, Tsuchida Y, Kawamoto K, Kubu T,

Hirasawa Y, et al. Outcome of conservative treatment with new

pogo-stick brace for unilateral Perthes’ disease. J Jpn Paediatr

Orthop Assoc 2000;9:85–8 (in Japanese).

25. Kasahara Y, Seto Y, Ohura K. Conservative treatment of Legg-

Calvé-Perthes disease with SPOC-brace and its restration pattern

of the affected femoral head. J Joint Surg 1986;5:93–104 (in

Japanese).

26. Cooperman DR, Stulberg SD. Ambulatory containment treat-

ment in Perthes’ disease. Clin Orthop 1986;203:289–00.

27. Wang L, Bowen JR, Puniak MA, Guille JT, Glutting J. An evalu-

ation of various methods of treatment of Legg-Calvé-Perthes

disease. Clin Orthop 1995;314:225–33.

28. Mose K. Methods of measuring in Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease

with special regard to the prognosis. Clin Orthop 1980;150:103–9.

29. Grzegorzewski A, Bowen JR, Guille JT, Glutting J. Treatment of

the collapsed femoral head by containment in Legg-Calvé-

Perthes disease. J Pediatr Orthop 2003;23:15–9.

30. Herring JA, Kim HT, Browne R. Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease.

Part II. Prospective multicenter study of the effect of treatment on

outcome. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2004;86:2121–34.

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Legg Calvé Perthes Disease in Czech Archaeological Material

A recurrent mutation in type II collagen gene causes Legg Calvé Perthes disease in a Japanese family

Intertrochanteric osteotomy in young adults for sequelae of Legg Calvé Perthes’ disease—a long term

Femoral head vascularisation in Legg Calvé Perthes disease comparison of dynamic gadolinium enhanced

Legg Calvé Perthes disease multipositional power Doppler sonography of the proximal femoral vascular

Acute chondrolysis complicating Legg Calvé Perthes disease

Modified epiphyseal index for MRI in Legg Calve Perthes disease (LCPD)

Legg Perthes disease in three siblings, two heterozygous and one homozygous for the factor V Leiden

Osteochondritis dissecans in association with legg calve perthes disease

Interruption of the blood supply of femoral head an experimental study on the pathogenesis of Legg C

Dynamic gadolinium enhanced subtraction MR imaging – a simple technique for the early diagnosis of L

Hip Arthroscopy in Legg Calve Perthes Disease

Computerized gait analysis in Legg Calve´ Perthes disease—Analysis of the frontal plane

Coxa magna quantification using MRI in Legg Calve Perthes disease

Osteochondritis dissecans in association with legg calve perthes disease

Interruption of the blood supply of femoral head an experimental study on the pathogenesis of Legg C

Legg Calve Perthes’ disease

Legg Calve Perthes’ disease

Legg Calve Perthes disease The prognostic significance of the subchondral fracture and a two group c

więcej podobnych podstron