GOSHEN

‘The house of

with a royal residence

temples

of

and

evidently not very far

E.,

and

on

the site, of modern Tell

I t is very ques-

tionable whether before

there were in the

eastern part of the valley any Egyptian settlements

except the fortification mentioned above at any rate,

it fully deserved the name that it came to bear in

later times-’ land

of

(this would hardly

apply to the old western district). The position

of

the

land colonised by Rameses was very advantageous.

It

possessed a healthy desert climate and was most fertile

as long as the canal to the Crocodile Lake was kept in

The extension of the canal of Ram(

to

the Ked Sea by Necho I. increased the commercial im-

portance of the district.

Quite recently, the repairing

of

the canal has trebled the population, now

this district, which forms a part of the modern province

Heroopolis-Patum thus became

an

im-

portant place

4

for the trade on the Red Sea, where

also the Romans built

a

fortified camp.

Thus we see that

and ‘land

of

were with the Egyptians hardly identical.

GOSPELS

.

T h e country of

could be

T h e

application to that (eastern) district, of

the (obsolete and rare) name

only the eighth (eastern) nome.

(vocalise

of

western

dome)

not

yet been shown on the (later) Egyptian monuments.

The Hebrew story (Nu. 33

of the Israelites marching two

d a y s (Rameses to Succoth, Succoth to Etham) through the

whole valley of

(instead of starting from its eastern

end) might suggest to some a mistake of

P, J E

placing the

country of the Israelites hetween Bubastus,

and Tell

(cp Naville). T h e probabilities, however, of such a

theory are small all sources seem to mean the same part of the

country.

Probably Heroopolis had, before the extension

of

the

canal by Necho

I.,

less importance, and the possibility

that once also the eastern district had P-sapdu as capital

and belonged to the district

is, therefore, not to be

denied.

It must he confessed that the geographical

texts upon which we have to rely date from Ptolemaic

times only. T h e division of the Arabian district may

have been different in earlier centuries.

Tradition has been exceptionally fortunate with

the name

Goshen

in particular identified Goshen with the

region

and the

of the Amalekit‘es.

The

of

Goshen to Sadir, a village N E . of

by Sa‘adia

(and Abu-sa‘id) is a s strange as the limitation to

(Old

Cairo) by Bar

Modern scholars have, on the contrary

frequently extended Goshen too widely: Ebers,

included

it the whole eastern delta between the Tanitic branch

Targ.

Jer. which made Goshen ‘the land of Pelusium’),

and the Bitter Lakes.

We can afford to neglect certain

hypotheses which date from the period before the decipherment

of

the hieroglyphics

for the situation erroneously assumed by

Brugscb, see

E

XODUS

,

13.

W.

M.

M.

GOSHEN

[BAFL];

I.

A

land mentioned in Deuteronomistic portions of Joshua

among other districts of

Canaan, Josh.

[AFL]),

[BAFL]).

It is strange to find

the name of Goshen outside the limits of Goshen roper.

Hommel

supposes that as the Israelites in Egypt multiplied, the

area allotted to them was extended, and that the strip

of country between Egypt and Judah, which still

belonged to the Pharaoh, was regarded as an integral

part

of

the land of Goshen. This is obviously

a

con-

servative hypothesis (see

E

XODUS

i., §

;

M

IZRAIM

,

The text, however, may need criticism. That

the M T sometimes misunderstands, or even fails to

observe, geographical names, is plain we have learned

so much from Assyriology.

Let

us

then suppose that

Goshen is wrongly vocalised, and should be

and

compare the name of the

town

(‘fat

soil’), the Gischala

of

Josephus.

Other solutions are

open we may at any rate presume that this old Hebrew

name had

a

Semitic origin, see

As they now stand, Josh.

and

do

the same geographical picture.

all the

Negeh and all the

land

of Goshen

and the

suggest that ‘the Goshen’ lay hetween the Negeb or southern

steppe region and the

or Lowlands. We might hold

that it took in the SW. of the hill-coimtry of Judah.

In Josh;

where we read ‘all the land of Goshen a s far as

we may ,presume that some words have dropped out after

Goshen.

Cp N

EGEB

,

4.

A town in the

SW.

of the hill-country of Judah, mentioned

with Debir, Anab, etc., Josh.

15

Probably a n echo

of

the old name of a district in the same region (see

I

)

.

Cp

Gesham.

T.

K.

C.

T h e words in

11

16,

G

o

S

’

P

E

L

s

CON

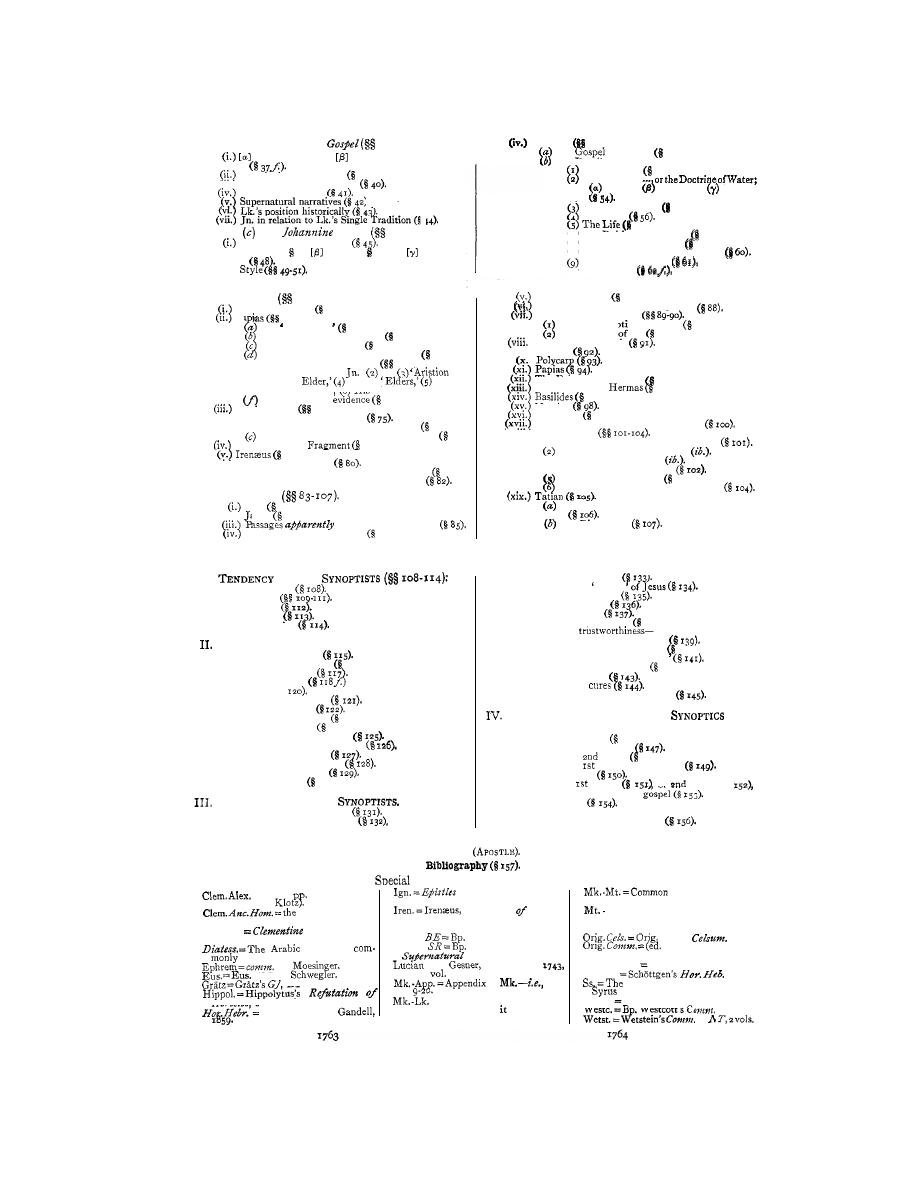

TENTS

AND ANALYTICAL.

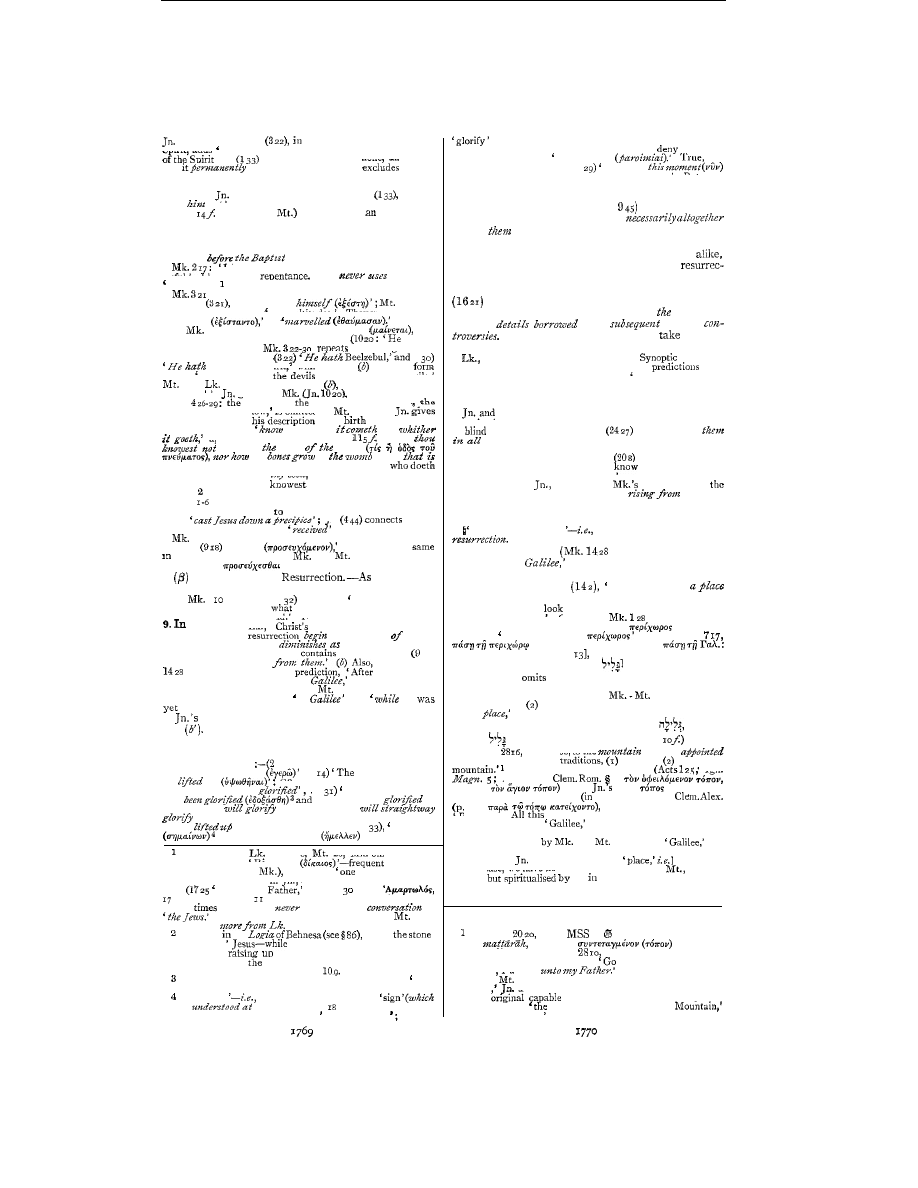

A.- INTERNAL EVIDENCE AS T O ORIGIN.

I.

T

HE

E

ARLIEST

T

RADITION

T

HE

T

RIPLE

T

RADITION

The edition of Mk. from which

Mt.

and Lk. borrowed

Mk.

relation to Mt. and

Lk.

Jn. in relation to the Triple Tradition

8-14).

(a)

Instances from the first part of Mk.

8).

of the Resurrection

( y )

Deviations of Lk. from Mk. (or Mk. and Mt.)

T h e Passover and the Lord’s Supper

( e )

T h e Passion

Conclusion and Exceptions

caused by obscurity

(5

IO

).

111.

D

OUBLE

T

RADITIONS

15-20).

Mk. and Mt. Jn. in relation to Mk. and Mt.

15).

Mk. and Lk

.

Jn. in relation to

Mk.

and Lk.

16).

Mt. and

or

Double Tradition

.

Acts

of the Lord’; (6) Words of the Lord

(iv.) Jn. in relation to ‘The Double Tradition’

A poetic description of the

new city is to be found in

t

of the canal always led immediately to a n

encroachment ofthe desert upon the narrow cultivable area.

The canal was

cubits wide (according to Strabo

ft.

according to Pliny

j o

yards according to traces near

ft. deep (according to Pliny; 16-17

Engl. ft.

according to modern traces).

The canal was repaired by

II.,

whence the name

of

the province Augustamnica from the

Canalis Trajanus.

Anastasi, 4 6.

1761

IV.

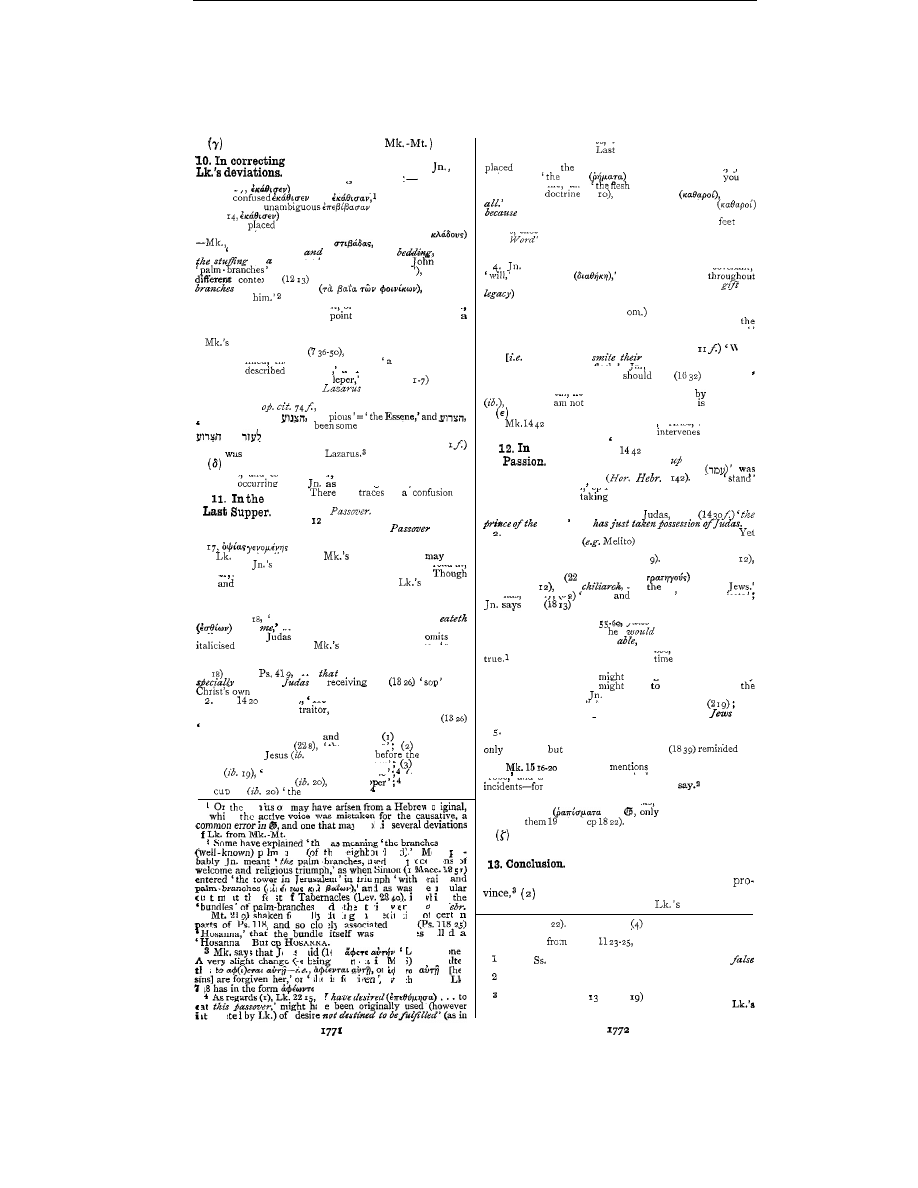

T

HE

I

NTRODUCTIONS

and

,

The effect of prophecy

Philonian Traditions

Justin and

Divergence of Mt. and Lk.

Jn. in relation to the Introductions

V.

THE

C

ONCLUSIONS

(Mt. Lk.

24-33.

(i.) The Evangelists select their evidence

24).

(ii.) T h e Period of Manifestations

25).

Discrepancies

.

27).

(v.)

view (‘proofs ’), 28.

(vi.) T h e Manifestation to the Eleven

Traces of Poetic Tradition

26).

Lk. Ignatius)

5

T h e

of

tradition

(vni.)

view (‘signs ’),

(ix.) Contrast between Jn. and the Synoptists

(5

33).

(x.)

Note on the Testimony of Paul

33

note).

VI.

S

INGLE

T

RADITIONS

34-63).

First

Gospel

34-36).

Doctrinal and other characteristics

343.

Evidence as to date

35).

Jn.

in relation to Mt’s.

Tradition

36).

The Coptic versions which simply transliterate, seem,

however to have lost all

Possibly the vocalisation of

disguised the Egyptian name to them. A woman pilgrim

of the fourth century places the ‘terra Gesse‘ 16 R. m. from

calling the capital ‘civitas Arabia.’ She believed

he

4

R. m. to the

E.

of this capital (see Naville,

meaning apparently

1762

(iii.)

(ii.)

(iii.)

(reff.

to

in Potter’s ed.

and margin of

epistle entitled

‘An ancient homily,’

in Lightfoot’s ed.

Clement.

Homilies, ed.

Schwegler.

Harmony

called Tatian’s

Diatessaron.

ed.

HE

ed.

ET.

Lightfoot, ed.

Heresies ed. Duncker.

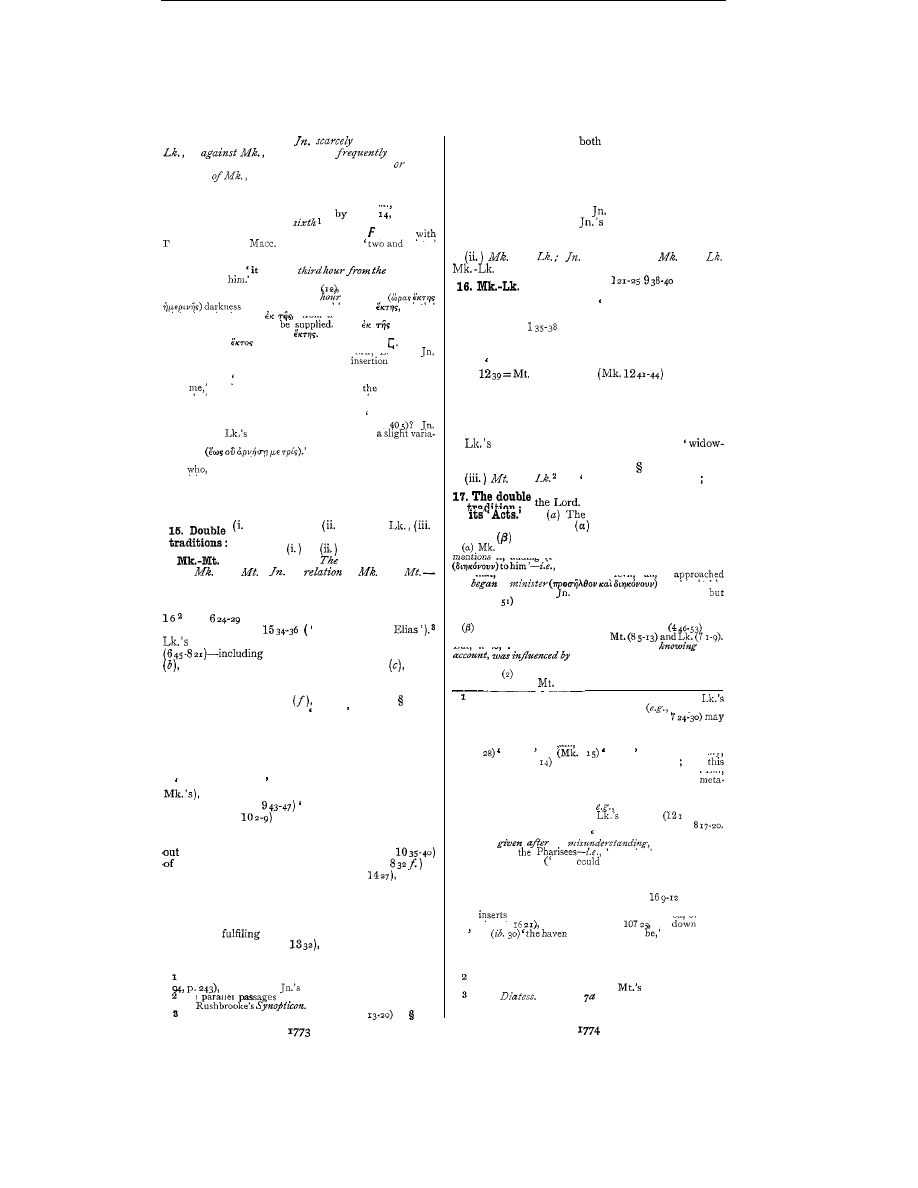

GOSPELS

( b )

The Third

37-44).

T h e Dedication,

Linguistic characteristics

Doctrinal characteristics

39).

A manual for daily conduct

Evidence as to date

of

Ignatius,

ed. Light-

Tradition

of

Mk.

foot.

Refutation

Heresies

Lk. =Common Tradition of

Mt.

(text of Grabe books and sections of

and Lk. (whether in Synoptic

or

ET

in ‘ante-N’icene Library’).

Lightf.

Lightfoot,

Bib.

Essays.

contra

Lightf.

Lightfoot,

Essays on

Huet, Kouen, 1668).

Religion.

Philo (Mangey’s vol. and page).

(ed.

Amsterdam,

Pseudo-Peter Gospel of Peter.

ref. to

and page).

Schottg.

2

vols.

to

Mk.

Codex (see T

EXT

), called

16

Sinaiticus.

=the Common Tradition

of

Tryph. Justin’s (ed. Otto).

Mk. and Lk. where

differs from

Westc

Westcott’s

on

John.

and Mt. where it differs from Lk.

Double Tradition).

Mt.

The

Gospel

45-63).

Hypotheses of authorship

[a]

Names,

46,

numbers, 47, and

quotations

on

B.

- EXTERNAL EVI

I.

S

TATEMENTS

64-82)

T h e Third Gospel

64).

P a

65-74).

His Exposition

65

a).

His account of Mk. and Mt.

65 b).

The system of Eusebius

66).

T h e silence of Papias on Lk. and Jn.

67).

(e) T h e date of his Exposition

68-73).

.

(I)

Was

Papias a hearer of

?

and

and

Jn. the

Papias’

His list

of the Apostles

(6) His relation to Polycarp.

Summary of the

74).

( a ) His titles of the Gospels

(6) Indications of Lk. as a recent Gospel

76).

T h e origin of Justin’s view of the Memoirs

77).

Justin Martyr

75-77).

The Muratorian

78).

79).

(yi.)

Clement of Alexandria

(vii.) Summary of the Evidence as to Mk. and Mt.

81).

(viii.) Summary of the Evidence a s to Lk.

and

Jn.

11.

Q

UOTATIONS

Paul

83).

(ii.) ames

84).

quoted from the Gospels

T h e Oxyrhynchus fragment

86).

GOSPELS

Structure

52-63).

T h e Gospel as a whole

52).

T h e Details.

The Prologue

53).

The Bridegroom

(a)

Galilee,

Jerusalem,

Samaria

(3

T h e Bread

of

Life

55).

The Light

(6)

The Raising of the Dead

58).

(7)

The Raising of Lazarus

59).

(8)

The Preparation for the Sacrifice

60).

The ‘Deuteronomy’

57).

(

I

O

)

The Passion

DENCE AS

TO

ORIGIN.

Structure

52-63).

T h e

as a whole

52).

I

T h e Details.

The Prologue

53).

The Bridegroom

Galilee,

Jerusalem,

Samaria

T h e Bread

of

Life

55).

The Light

56).

T h e Life

57).

The Raising of the Dead

58).

The Raising of Lazarus

59).

The Preparation for the Sacrifice

The ‘Deuteronomy’

The Passion

Clement of Rome

87).

T h e Teaching of the Twelve Apostles

T h e Epistle of Barnabas

The Great Apophasis

(

I

Alleged Synoptic Quotations

89).

Anticipations

Jn.

go).

(ix. Ignatius

e Shepherd of

96).

The hpistle

to

Diognetus

95).

T h

97).

Marcion

Valentinus

99).

Summary of the Evidence before Justin

(xviii.) Justin Martyr

I

(

I

)

Minor apparent Johannine quotations

‘Except ye be begotten again’

(3)

Other alleged quotations

(4)

Abstentions from quotation

Inconsistencies with Jn.

103).

Summary of the evidence about Justin

...

Traces of Jn. as a recent ‘interpretation’

T h e Diatessaron

B.-HISTORICAL AND SYNTHETICAL.

A.-SYNOPTIC GOSPELS.

I.

IN THE

In general

I n Lk.

IO

I n Mt.

I n

Mk.

Conclusion

T

HE

S

YNOPTIC

P

ROBLEM

.

Tradition theory

Dependence theory

116).

Original gospel

Original Mk.

Logia

(5

Two-source theory

Extent of logia

Special Lk. source

123).

Smaller sources

124).

Theories of combination

Review

of

classes of theory

Use of Mt. by Lk.

Sources

of

the sources

Critical inferences

Semitic basis

130).

T

RUSTWORTHINESS OF

Fundamental principles

Chronological statements

Order

of

narratives

I

3).

Occasion of Words

Places and persons

Later conditions

Miracle stories

Resurrection of Jesus

138).

Absolute

( a ) About Jesus generally

(b)

About Jesus’ miracles

140).

Inference regarding the ‘signs

Metaphors misinterpreted

142).

Influence of O T

Miraculous

Conclusion a s to words of Jesus

A

UTHORSHIP

AND

D

ATE

OF

A N D

THEIR SOURCES.

Titles of gospels

146).

Statements of Fathers

Author of

gospel

148).

Author of

gospel and the logia

Date of logia

Date of

gospel

of

gospel

(5

author and date of 3rd

Conclusion

Gospel of Hebrews ($155).

Other extra-canonical gospels

B.-FOURTH

GOSPEL.

See

JOHN

abbreviations used in this article.

GOSPELS

[The aim of the

article

to set forth with

sufficient fulness the facts that have to be taken into

account in formulating

a

theory of the genesis of the

gospels, to record and

some of the more

portant theories that have been proposed, and to

cate if possible the present position of the question and

the apparent trend of thought.

Its two parts, as will appear from the prefixed tabular

exhibit of their contents, are partly independent, partly

complementary.

Roughly it may be said that the first

GOSPELS

is relatively full in its account

of

the

of the gospels as a basis for considering their mutual

relations, and in its survey of the external evidence as

The second

mainly at

giving

ordered account of the various questions bear-

ing on (especially) the internal evidence that have

raised

by

scholars

in

the long course of the development

of gospel criticism, and at attempting to find at least a

provisional answer.]

. to origin.

A .

INTERNAL EVIDENCE

AS

T O ORIGIN.

I.

T

HE

E

ARLIEST

T

RADITION

.

Roughly it may be said that, of the Synoptists, Mk.

exhibits the Acts

shorter Words of the Lord Mt.

a combination of the Acts with Discourses

of the Lord, the latter often grouped

together, as in the Sermon

on

the Mount

Lk. a second

of

Acts with Discourses,

which an attempt

is

made to arrange the Words and

Discourses chronologically, assigning to each the circum-

stances that occasioned it.

A

comparison shows that Mt.

and

where Mk. is silent, often agreewith one another.

This doubly-attested account-for the most part con-

fined to Discourses, where the agreement is sometimes

verbatim-may be conveniently called

Double

Tradition.’ Where Mk. steps in, the agreement between

Mt. and Lk. is less close and a study of what may be

called the Triple Tradition,’

the matter common

to Mk., Mt., and Lk., shows that here

and

as

a rule, contain nothing of importance in common. which

is

not

found

i n

our

( o r

rather in a n ancient

edition

of

containing

a

f e w

for

[see below,

This leads to the

conclusion that, in the Triple Tradition, Mt. and Lk.

borrowed (independent&

of

each

other)

either

our

(more

f r o m some document

2

embedded

in

Any other hypothesis requires only to he stated in order to

untenable.

For example

:

(

I

)

that Mt. and Lk. should

agree

accident, would be contrary to all literary experience ;

if

and Lk. borrowed from a common document contain-

ing Mk or (3) differing in important respects from Mk or

Lk.

from

or Mt. from Lk

and

would contain

not

in

( 5 )

if Mk. borrowed from Mt. and from Lk., he must have

his narrative

so

to insert

almost

and

word

common

to

and

in the

passage

before

him-a

hard task, even for a literary forger of these days, and an im-

possibility for such a writer a s Mk.

The Fourth Gospel

called Jn.) does

the Synoptic‘

‘repentance,

faith,,

baptism,‘

‘rebuke,’

‘sinners,

2.

John.

‘disease

‘possessed with a devil,‘

cast

devils

‘unclean

‘leper

‘leaven,’

’enemy,’ ‘hypocrisy,

‘adultery,’

wbe

‘rich,’

‘riches,’ ‘mighty work

Instead of

Jn. uses ‘have faith

‘Faith,’ in Jn. is ‘abiding

Christ.’ The Synoptists say that prayer will he

if we

have faith : Jn. says (15

If

y e

in

and

my words

you,

ask whatsoever ye will, and it shall be done unto

you.

Except in narrating the Crucifixion, Jn. never mentions

cross’ or ‘crucify,’ but he represents Jesus as predicting

being ‘uplifted’ or ‘glorified.’

rarely occurs but the necessity of

the kingdom of

God as little children’ is expressed by him in the necessity

(verbally different, hut spiritually the same) of being ‘born from

above.‘

Since the author

of

the Fourth Gospel must have

For the meaning of the emphasised ‘the

’

see helow

T h e hypothesis of an Oral Tradition, a’s the

sole

of

t h e similarities in the Synoptists, is contrary both to external

and to internal evidence.

3

‘The kingdom of God or

‘of

heaven,’ occurs in Jn. twice,

in the Synoptists more

times.

In Jn. the Synoptic ‘child

known.

(Eus.

the substance

of

the

it is

antecedently probable that, where the Synoptists differ,

if

favours one, he does

so

deliberately.

Inde-

pendently, therefore, of its intrinsic value,

is im-

portant as being, in effect, the

commentary

on

the

Synoptists.

11.

T

HE

T

RIPLE

Here we have to consider : (i.) The edition

of

Mk.

from which Mt. and Lk. borrowed;

(ii.)

Mk. in relation to Mt. and Lk.

Jn. in relation

to

and

Lk.

The

Edition

of

from

which

and

borrowed

differs from

Mk.

itself merely in a few points

indicating a tendency to correct

style.

The most frequent changes are (a)

to

substitute

for

and to insert pronouns,

for the sake of clearness. But

is often apparent

(6) a tendency

to

substitute more definite, or

classical or appropriate words. For example,

are substituted for the single

(Mk.

2

applied to wine and wine-skins),

(or some other

for the barbaric (Mk. 2 4

for (MU.

for the unheard of

(Mk. 2

is

by the

following; bracketed additions : Mk. 4

mystery

of God; (3

[his brother]; (44)

In Mk.

for ‘them Mt. and Lk.

heart.’

(c)

there is’condensation

4

IO]

or an

unusual word

[of a plant] is changed to

a

more

one

;

or a less reverential phrase

2 7 )

to

a more reverential one

In

altered into

or

possihly because

means in

(four or five times)

This follows from the generally admitted fact that versions

of the Three Synoptic Gospels were welt known in the Church

long before the publication of the Fourth (see helow, ‘External

Evidence’). An interesting testimony to the authority of our

Four Canonical Gospels, and also to the later date of the Fourth

comes from ‘the Jew’ of Celsus, who says that (Orig.

2

certain believers, ‘as though roused from intoxication to

control (or to self-judgment,

sir

alter the character of

the Gospel from

its first

in

four-

fold

and

fashion

and

it

that they might have wherewith to

gainsay refutations

Celsus apparently

that there was first an original

Gospel, of such a kind as to render it possihle for enemies to

make a charge of ‘intoxication (perhaps being in Hebrew and

characterised by eastern metaphor and hyperbole), then, that

there were three versions of this Gospel, then four, thus making

an

interval between the first three and the fourth, which he, does

not make between any of the first three.

ap ears to refer to still later apocryphal Gospels.

seemed more appropriate for history. At

all events Lk.

never

(without

etc.)

Jesus.

The only apparent instance is Lk.

unto them Peace he unto yon.

This is expunged

dorf, and

in double brackets by

W H .

Alford condemns

Tischendorf on the ground that

authority is weak.’

internal

evidence

is strong.

3

The deviations of

Mt.

and Lk. from Mk. are printed in

distinct characters in

Mr. Rushbrooke’s

which is

indispensable for the critical study

of

this question.

It

follows

the order of Mk.

The word ‘manifold

1766

GOSPELS

GOSPELS

‘the cleft

of a rock.’

Once at least our Mk. (9

:

dvahov

to have

traditio;, Mt. and Lk.

the older

:

there

is

order,

is

on

the

Mount, indicating that both Mt.

and Lk. derive the saying, not from

but from a different

source,

which come the portion: common to Mt. and Lk.

above called The Double Tradition.

An examination of the deviations from Mk. common

to

Mt. and Lk. in the Triple Tradition confirms the

view that Mt. did not borrow from

L k . ,

nor

L k .

from

Mt.

Had either borrowed from the other, they would

have agreed, at least occasionally, against Mk. in more

important details.

(ii.)

in relation

t o

and

is

a

remark-

able fact that-whereas the later Evangelists, and other

writers such as Barnabas and Justin,

appeal largely to detailed fulfilments of

prophecy-Mk. quotes

no

prophecies in

his own

and gives no miraculous

incidents peculiar to himself except (Mk.

an ancient

and semi-poetical tradition of the healing of the blind.

H e makes

no

mention of Christ’s birth or childhood,

a n d gives no account of the

Occasionally Mk. repeats

the

same thing in the formofquestion

and answer.

may sometimes he a mere peculiarity of style

e.g

2

3

:

but in many cases (1

32

42 3

[compared

3

4

5

12 44

etc ) he seems

t o

have had before him two

versions of one saying

in his ‘anxiety to omit

to

have inserted hoth.

in connection with un-

clean spirits see

44 37-12

for others, relating

to the

of people round Jesus, the publicity of his

work and his desire for solitude, see

2

3

etc. (some paralleled in Lk.,

not so fully or

gra

Mk. abounds with details as to the manner

and gestures of Jesus (see 3

31-37

I n some

these, Aramaic words are given a s his very utterances,

5 41

14

36.

Sometimes Mk. gives names mentioned by no other

writer (cp 3

8

10 46).

I n some circumstances,

elaboration

of

portant detail (and especially the introduction of names),

instances of which abonnd in the Apocryphal Gospels,

would

indicate

a

late writer. But Mk. often emphasises

and elaborates points omitted, or subordinated, by the

other Evangelists, and likely to be omitted in later times,

as

not being interesting or edifying.

For example Lk. and Jn. subordinate facts relating to the

ersonal

influence and execution of John the

Now Acts

3

that several years after Christ’s

death ‘the baptism of John’ was actually overshadowing the

baptism of Christ among certain Christians. This being the

case, it was natural for the later Evangelists to

references

t o

the Baptist. Lk., it is true, describes

birth

in detail: but the effect is to show that the son of Zachariah was

destined from the womb to be nothing hut a forerunner of the

Messiah. Jn. effects the same

in a different way, by

recording the Baptist’s confessions of Christ’s preexistence and

sacrificial mission. I t is characteristic of

early date as

well

as

of his simplicity and freedom from controversial

that, whether aware or not of this danger of rivalry, he set down:

just as he may have heard them, traditions

the Baptist

that must have interested the Galilean Church far more than

Churches of the Gentiles.

Another sign

of

early composition

is

the rudeness of

Greek.

Mk. uses many words

by

6.

Rude

Phrynichus,

(5

23)

a s the

Constitutions improves the had

(Taylor’s

so Lk. always (and sometimes

Mt.) corrects these

Such words (which stand on

quite a different footing

Greek, such as we find in

(1025)

Almost the only addition of importance in this ‘corrected

edition of Mk.’ is

‘Who

it

thee?’ added to explain the obscure Mk. 1465 ‘Prophesy.

T h e parenthesis in Mk. 1 is the only exception. This was

probably an insertion in the original Gospel (see

5

8).

3

For proof that

Gospel terminates a t

168,

see

WH

on Mk. 16

which is there pronounced to he ‘a narrative

of Christ’s appearances after the Resurrection,’ found by ‘ a

scribe or editor ‘in some secondary record then surviving from

a

preceding

‘its authorship and its precise date

must remain unknown

;

it is, however apparently older than the

time when the Canonical Gospels

received for

though it has points of contact with them all, it contains

attempt

harmonise their various representations of the course

of events.

Papias, quoted

Eus. (3 39)

:

‘For he (Mk.) took great

care about one matter,

io

omit

nothing

o

f

what

he

heard.’

Introduction) might naturally

their place in the

dialect of the slaves and freedmen who formed the first congrega-

tions of the Church in Rome

;

but in the more prosperous days

of the Church they would be corrected.

Again,

a

very early Evangelist, not having much

experience of other written Gospels, and not knowing

exactly what

most edify

Church, might naturallv

stress on

vivid expressions and striking words, or reproduce

anacolutha, which, though not objectionable in discourse,

are unsuitable for written composition.

Many such words are inserted

Mk. and avoided

Mt. or

Lk. or by

(13s)

For irregular constructions

12

(altered

5

Note also the

change

of construction from

to the infinitive in 315, as compared with

3 1 4

and the use

of

to ask a question (2x6

The

of Mk. are

known; see 627 7 4

39.

Those

in 1214

and

in

Mk. shares with

Less noticed but more noteworthy, are the uses of rare, poetic,

or prophetic’ words

(7

32

8

23

which may indicate a Christian

or hymn

the basis

Mk. also

contains stumbling-blocks

in

the way

of

weak believers, omitted in later Gospels,

and not likely

to

have been tolerated,

except in

a

Gospel of extreme antiquity.

example

‘ H e

was

not

to do there any

work

.

34)

all

sick are brought to Jesus, hut he heals

only

whereas Mt. (816) says that he healed all, and Lk.

that

he

healed each one

;

his mother

and brethren attempt to lay hands on him, on the ground that

he was insane.

a n ambitious petition is imputed to

James and Johh, instead of (as Mt.)

t o

their mother;

Pilate ‘marvels’

at

the speedy death of Jesus which might

have been used to support the view (still maintained by a few

modern critics) that Jesus had not really died Mk. omits (6 7)

the statement that Jesus gave power (as Mt.

Lk. 91) to his

apostles to heal

he

enumerates the different

stages

which Jesus effected a cure, and describes the cure

as a t first, only partial

the fig-tree, instead of being

up ‘immediately’ (as Mt. 2119

is

not

observed to he withered till after the interval of a day.

(iii.)

in

the

Instances from the first part of

following

comparisons will elucidate

relation

( I t will be found

that Jn. generally supports a combination

.

of

Mk.

and Mt., and often Mk. alone,

to the Triple Tradition.

against Lk. the exceptions being in those

passages which describe the relation of John the Baptist

There Jn. goes beyond Lk.

Mk. 1

‘As it is written in Isaiah,

If these prophecies,

wrongly assigned to Isaiah are not a n early interpolation, they

are the only ones quoted

the

Evangelist

Mt. and

Lk. assign one of these prophecies

assigns

to

the

Baptist, so a s to

the willing subordination of the

latter I am [but] the voice’).

Mk.

mentions no suspicion among the Jews that the

Baptist might be the Messiah. Lk. mentions

a silent

‘questioning‘ (that does not elicit a direct denial).

adds a

question (1

art thou?’ followed

a

I

not

Mk.17:

me.’

Rejected by

Lk.

(possibly a s being

liable to an interpretation derogatory to Jesus), but. thrice

repeated by

Jn.

27

such a context a s to

to

Christ’s

precedence

Mk.18: ‘shall baptize you

with

f h e

Holy

Spirit,’

omitting

is added by, Mt. and Lk. Jn. goes with

Mk.

133)

:

Mk 1 mentions ‘Jordan in connection with the baptism of

Jesus:

k. does

not

(though he does afterwards in his preface

to the Temptation).

Jn. (1

does,

with details of the place.

(Note that Lk. never mentions the Synoptic ‘beyond

He it is that

with

the

Holy

Spirit.’

I t

is

beside the mark to reply that these words are used,

occasionally, by classical prose writers. T h e point is, that

occurs in N T

only

a n d

a

account

healing in

2034,

occurs

i n N T

ninety times!

In the canonical books of OT,

occurs only

in Proverbs.

occurs only here in NT, and only twice

(apart from a leper’s

scab in OT, and there in poetical

passages.

(practically non-occurrent in Greek litera-

ture, see Thayer) is found nowhere in the Bible, except in

of

Is.

356,

and in

account of the man who had (Mk. 732)

impediment in his speech.’

I t

omitted also in 3

(where

D and Ss.

add it).

The

of

and Lk. to Mk. will be found

by

Synopticon.

I t may

sumed that in this section, Mt. agrees with

except

where

indicated.

GOSPELS

GOSPELS

has it thrice.) Lk.

describing the descent of the

Spirit adds in a bodily shape.‘ Jn. implies that the descent

was

a

sign to the Baptist alone and States

that

abode on Jesus.

Thus he

‘bodily

shape,’-at all events in the ordinary sense.

Lk.

alone (1 36)

had stated that the Baptist was connected with Jesus through

family ties;

represents the Baptist a s saying

‘And

I

knew

not.

Mk.

1

(possibly also

leaves room for

interval after

the Temptation, in which the reader may place Christ’s early

teaching in Jerusalem before ‘John was betrayed.

Lk. 414,

omitting the mention of John, appears to leave m o interval. Jn.

repeatedly says, or imphes, that the early teaching

took place

(324

4

I

3)

was

imprisoned.

I

have not come

to,

call the righteous, but the

sinful.

Lk. adds ‘to

Jn.

the

word

repentance.’

puts

into the mouths of Christ’s household or friends

the words

‘ H e is

beside

and Lk.

seem to transfer this to the multitudes.

They render it ‘were

astonished

or

Jn. goes

with

in mentioning a charge of ‘madness’

and

connecting it with the charge of possession

hath a

devil and is

mad’).

the charee of the

Pharisees,

( a )

in thd form

(3

a n unclean spirit while adding

a milder

(322):

In the prince of

h e casteth out the (devils.

and

reject (a) and adopt

defining ‘prince’ by

‘Beelzebnl.

aoes with

‘ H e

hath

a devil.’

Mk.

parable of

seed that springeth up

sower

‘

knoweth not how

is

omitted by

and Lk.

the essence of this in

of the

from the Spirit,

as

to which, we (38)

not

whence

and

apparently modelled

on Eccles.

:

‘ A s

what

is

way

wind

the

in

of

her

with

child,

even so thou knowest not the work of God

all.

I n the morning

sow

thy

seed

and in the evening withhold

not thine hand

:

for thou

not which shall prosper, this

or that.’

Mk. 6

:

‘ A prophet

in

his own country.’ Lk. alone connects

this proverb with a visit

Nazareth,

in which the Nazarenes

try to

Jn.

it

with

a visit in which the Galileans

Jesus. Cp

N

A

Z

A

RE

TH

.

Here Lk., alone of the evangelists, represents

Jesus a s

‘praying

and he does the

four other passages where

and

omit

it.

Jn.

never

uses the word

throughout his Gospel.

Predictions of the

to these

Mk.

and

Lk.

give

us

a

choice between two difficulties.

( a )

9

(comp. also 9

says, that the disciples ques-

tioned among themselves

was the meaning of rising from

the dead

Yet what could he clearer? I n

predicting

Lk.

predictions of death and

Resurrection.

with fulness

detail,

which

the Gospel

proceeds;

and the last prediction of death

a statement that

45)

‘it was

as

it

were

veiled

them.

so

whereas Mk.

(and Mt.) contains the

I

have been

raised up,

I

will g o before you t o

Lk. omits this; and

subsequently, where Mk. (16

7)

and

repeat or refer to this

promise, Lk. alters the words

to

into

he

in

Galilee.’

relation to ( a ) and

(6)

is

as

follows in (a’)

and

(a’)

Jn.

makes it obvious why the disciples conld not

understand Christ’s predictions.

Take the following

19)

‘Destroy this temple and

in three

days I will

raise

it

up

; (3

Son ’of man must

be

up

(1223)

‘ T h e hour is come that the

Son of man should be

.

(13

Now

hath

the Son of

man

God hath

been

in

him, and Gqd

him in himself and

him.

Who was to conjecture that, when Jesus spoke of

being

‘

from the earth,’ he said this (12

signifying

by what death he was

to die’? or that

8 27-29.

‘Call,’ used by

41

times

26, Mk. only 4, is used

by Jn. only twice.

Righteous

in Mt. and

Lk. (but only twice in

to describe

who observes the

law’-is used but thrice in Jn. and then in the higher Platonic

sense

0

righteous

and see 5 724).

times in Lk., only

times in hft. and

Mk.

together, occurs

only

4

in Jn., and

except

in

the

of

Jn. differs in expression from Mk. and

; but

he differs f a r

Similarly,

the

‘Raise

cleave the tree,

mainly referring to the Baptist’;

doctrine about

stones a s children to Abraham. and

about cutting down

barren tree of Jewish formalism-may

possibly have had in his mind Eccles.

The aorist cannot be exactly expressed in English

:

hath

been’ is nearer to the meaning than

‘

was.’

‘Signifying

representingunderafigure

or

n o

one

the time).

In 21

the cross is ‘signified’

more clearly by the ‘stretching out of the ‘hands

but no

meant ‘glorifying’ the Father, and hence the Son, by

the supreme sacrifice on the Cross? No

one

can

that these

were what Jesus calls dark sayings

the

disciples contradicted him : (16

Behold at

speakest thou clearly and utterest no dark saying.

But they

were wrong.

Jn. seems to say, therefore, not that Christ’s teaching,

thoughclear, was ‘concealed’

(Lk.

from the disciples

supernaturally, but rather that it was

beyond

till the Spirit was given.

Imbued with the

popular belief that resurrection must imply resurrection

in

a

fleshly form, visible to friends and enemies

how could they a t present apprehend a spiritual

tion, wherein the risen Christ must be shaped forth

by

the Spirit, and brought forth after sorrow like that of

‘the woman when she is

in

travail?’

Mk.

and

Mt. seem

to

have read

i n t o

utterances

of

Jesus

from

f a c t s

o r

Towards these,

Lk.

and Jn.

different

attitudes

starting a t first in accord with the

Tradition,

gradually drops more and more of the definite

; and

a t last, when confronted with the words, After

I

am raised,

I

will

go before you into Galilee,’ omits the promise altogether.

Jn., on the contrary, recognises that the predictions of Christ

were of a general nature, though expressed in Scriptural types.

Lk. differ also in their attitudes towards Scripture a s

‘proving’ the Resurrection.

Lk.

represents the

two

travellers

a s

to the risen Saviour, till he

‘interpreted t o

the

Scriptures the things concerning himself.’ Jn.

expressly says that the belief of the beloved disciple

precede4

the knowledge of the Scriptures:

‘And he

saw

and

believed

;

for not

even

y e t

did they

the Scripture, how

that he must needs rise from the dead.

In the light of

returning to

statement that

disciples discussed together ‘what

the

the

dead

might mean,’ we have only to suhstitute ‘this’ for ‘the,’ and i t

becomes intelligible. Every one knew what ‘rising from the

dead’ meant. But they did not know the meaning of

this

kind

of rising from the dead

what

Christ

said

about his

(6’)

T h e promise

and Mt.), ‘ I will

go

before you to

occurs in close connection with

Peter’s profession that he will not desert Jesus. Jn. has,

in the same connection

I

go to prepare

for you.’

This leads us to

elsewhere for a confusion between

‘Galilee’ and ‘place.

Comparing

with Lk. 437,

we

find that Lk. has, instead of ‘The whole

of

Galilee,’

the words every place of the

(so

also in Lk.

stands where we should expect

so Chajes [Markus-studies,

who also independently offers

the

same theory [double meaning of

to account for Lk. 4 37).

In

Mk. 3 7, Lk.

‘Galilee.’

The question, then, arises,

whether, the original, may have been some word signifying

‘region,

or ‘place

which (

I

)

interpreted to

mean

‘Galilee,’

Jn. ‘the

place

(of my Father)’ or ‘the

(holy)

while (3) Lk. found the tradition so obscure

that h e omitted it altogether. Now the word

a longer

form of

(‘Galilee’), is used to mean (Josh. 22

‘region.’

Again, Mt.

‘to Galilee to the

where he

for them,’ suggests two

‘Galilee,’

‘appointed

Lastly, hesidrs many passages

Ign.

Barn. 19

I

;

5 ,

and also

where

word

is used, with

a n attribute, to mean ‘place

the next world),’

978,

uses the word absolutely of

leads to the inference [which

is highly

probable a s regards

and which further knowledge

might render equally probable as regards ‘place’] that an expres-

sion, misunderstood

and

a s meaning

and

omitted by Lk. because he could not understand it a t all, was

understood by

to

mean [my Father’s

‘Paradise.’

In any case we have here a tradition of Mk. and

rejected

by Lk.,

Jn.

such a way as to throw light

on

the different views taken by Lk. and Jn. of Christ’s sayings

about his resurrection.

one is said to have understood the ‘stretching out,’ and the

context almost compels us to suppose that it was not understood.

In

I

Sam.

where

of

have a corrupt reproduc-

tion of

Sym. has

‘appointed

place.’

Also

compare Mt.

‘ G o tell my brethren to

depart to

Galilee,’

with Jn. 20 17,

to my brethren and say

unto them I

ascend

Does

not this indicate

that what

understood a s meaning ‘Galilee’ or ‘appointed

mountain

understood a s meaning ‘heaven’? This points

to

some

of being expressed by ‘the place,’

‘the holy place,’

(place) of the Father,’ ‘the

‘the

Holy Mountain.

Paradise.

GOSPELS

GOSPELS

Deviations of Lk. from Mk. (or

caused

by obscurity, appear to be corrected,

or

omissions supplied, by

in

the followine instances

Mk. (11 7

and Mt. say that Jesus

‘ s a t on the ass’.

Lk. first

with

and then substituted

for the latter the

‘they put him thereon.’

Jn. (12

goes with Mk. T h e Synoptists all mention

‘garments,’

on the ass and strewn in the road. But Mk.

and Mt. mention also the ‘strewing’ of branches (Mt.

however, calling them

a word that mostly

means

litter,’ or ‘grass

straw used

for

or

for

of

mattress.

This Lk. omits.

inserts

(without mentioning ‘garments

but in a

context:

‘They took (in their hands)

the

of

the palm trees

and went

forth to meet

Whether Jn. or Mk. was right

or whether both were right

is not now the question.

tradition of Mk. possibly as being difficult, Jn. modifies it, or

substitutes a kindred one.

T h e

is that where Lk. omits

(143-9) account of the anointing of Jesus by a woman

is either omitted by Lk.

or placed much earlier and

greatly modified the woman being called

sinner,’ and the

host being

as ‘Simon a ‘Pharisee.’

Mk. and Mt.,

however, call him ‘Simon the

and Jn. (12

suggests

that the house belonged to

and his sisters.

I t is

not impossible that the difference may be caused by some clerical

error. Chajes,

accounts for ‘Simon the leper’ by

aconfusion between

‘the

the leper.’ May there have

further confusion between

and

‘Lazarus’? Jn. apparently guards the reader

against supposing the woman to he a sinner, by telling

us (11

that it

Mary, the sister of

The Passover and the Lord’s Supper.-The

Synoptists and especially Lk seem to represent the Cruci-

fixion as

after.

occurrine before. the Paschal

-meal.‘

are

of

in

Lk. between the Day of

Preparation and

I t was one thing to

(Mk. 14

and Mt.)

‘prepare to

eat

the Pass-

over,’ and another to (Lk. 228)

‘prepare the

that we

may eat it,’ which Lk. substitutes for the former. Also Mk.

14

(which Mt. adjusts to a different context,

and

omits) indicates that

original tradition

have

agreed with

view: for no one would have been abroad a t

or after sunset when the Passovermealwas to be eaten.

Mk.

Mt. ’in parts unquestionably sanction

view. they

do

not express it so decidedly a s Lk., and they contain slight

traces of a n older tradition indicating that the Last Supper

was on the Day of Preparation.

I

.

Mk. 14

One of you shall betray me, he that

with

was perhaps a shock to some believers, a s

indicating that

partook of the bread. Mt.

the

words, retaining

more general phrase,

while

they were eating.’

Lk. omits ‘eating,’ having simply, ‘ t h e

hand of him that is to betray me is with me on the table.’ Jn.

(13

quotes

‘ H e

eateth my bread

.

.

.

,’and

mentions

as

the

from

the D a y of

hands.

Mk.

(and Mt.)

H e that dippeth his hand in the dish

with m e ’ will be the

is omitted by Lk. Jn. com-

bines a modification of this with the foregoing; Jesus

dips the sop’ and gives it to Judas.

3.

Lk. differs from Mk.

Mt. in

mentioning the

meal (apparently) as

the Passover

mentioning

a

‘cup’ which

17)

‘received’

meal, and

bade the disciples ‘distribute to one another

inserting the

words

D o this a s a memorial of me

(4) mentioning

a second cup, that was

‘after sup

(5)

speaking of

the

a s

new covenant.

I n

all

these points

in

of the

in

on

with

her

would

is what

Lk. amplifies and dignifies while Jn. appears to subordinate,

the circumstances of the

Supper. What Jn. had to

say

about the feeding on the flesh and blood of the Saviour, he

earlier, in

synagogue at Capernaum. There Jesus

insists, (663)

words

that I have spoken

to

are

spirit and are life

’

and,

profiteth nothing.’ Now he

reiterates this

(13

‘ye are clean

but

not

This, when compared with (15 3), ‘ye are clean

of

the word that (have spoken untoyou,’ indicates that

participating in the bread and wine and washing of

was

useless except so far

as

it went with spiritual participation in

‘the

himself.

A climax of warning is attained by

making Judas receive the devil when he receives the bread

dipped in wine by the hand of Jesus.

avoids the ambiguous Synoptic word ‘covenant’

or ‘testament

and makes it clear,

the final discourse, that he regards the Spirit as a

(or

that implies nothing of the nature of a bargain or

compact.

5.

Mk.

14

27

(and Mt.; but Lk.

‘All

y e shall be caused to

stumble; for it is written, I will smite the Shepherd, and

sheep shall be scattered abroad,’ was likely to cause a ‘scandal

-

as

though God could ‘smite’ his son. This may be seen

from Barnabas, who gives the prophecy thus

:

(5

hen

they

the Jews] shall

own shepherd, then shall

perish the sheep of the flock. Jn. while retaining Christ’s

prediction that the disciples

be

‘scattered

effectively destroys the ‘scandal’ by adding that, even wheh

abandoned by them he would not be abandoned

the Father

‘And yet

I

alone, because the Father

with

me.’

The Passion.-The facts seem to be as follows :-

I

.

and Mt. place the words, ‘Arise

let us go’ a t

Lk. omits all that

between ( a )

Mk. 14 38

Watch and pray.

. .

temptation,’

and

(6) Mk.

‘Arise, let us go,’ having

merely (2246)

‘Stand

and pray

.

.

.

temptation.’

Now ‘to stand

‘nothing else than to pray’

2

But

might also mean ‘watch cp Neh. 73. Lk. may have considered

(6) a duplicate of

(a),

the meaning to he ‘stand fast and

pray.‘ Jn. places the words ‘Arise, let us go,’ at the moment

when Jesus feels the approach, not of

hut of

Lk. omits

all)

mention of the ‘binding’ of Jesus.

early Christian writers

regarded it as a symbolical

act, being performed in the case of the intended sacrifice of

Isaac, the prototype of Christ (Gen. 22

Jn. inserts it (18

a s does Mk. 15

I

(and Mt.).

3.

Lk. speaks of

52)

‘generals

(UT

of the temple.’

Jn.

says (18

‘The

and

officers of the

Lk. has loosely (3

Annas

Caiaphas a s ‘high priests

that

Caiaphas was high priest, and Annas his

father-in-law.

the arrival of Judas.

the

world

who

4. According to Mk. 14

false witnesses asserted that

Jesus had declared that

destroy the temple.

Mt. alters ‘would’ into was

and implies that, though

what had been previously testified was false

this

may have been

Lk. omits the whole.

I n his

the destruction of

the temple by the Romans was accepted by Christians as a

divine retaliation. which

he reearded as inflicted bv

Jesus himself, so’thaf he

wish

avoid saying that

testimony was ‘false.

says in effect, ‘Some words about

destroying “the temple

had been uttered by Jesus

but

they referred to “the temple of his body.” And

the

were

the-“destroyers.”’

Mk. 15

6

(and Mt.) says that it was the custom to

release a malefactor a t the feast.

Lk. omits this.

Jn. not

inserts it,

adds that Pilate himself

the

Jews of it.

6.

(and Mt.)

the (purple or scarlet)

‘robe and the ‘crown of thorns.

Lk. omits these striking

what reason, it

is

difficult to

Jn. inserts

both of them.

7.

Mk 1465 alone of the Synoptists mentions ‘blows with

the flat ‘hand”

; in

in

Is.

506).

Jn. also

mentions

3 (and

Conclusion and Exceptions.-The instances above

enumerated might be largely supplemented.

The

conclusion from them is that-setting

aside

(

I

)

descriptions of possession,

and other subjects excluded from the Johannine

allusions to John the Baptist,

( 3 )

a

few

passages where Jn., accepting

development,

Mt.13

17

Lk. 17

Also (3) and

and (5) may be interpola-

tions (but more probably early additions, made in a later edition

of the work)

I

Cor.

or (more probably) from

tradition.

D and

destroy this possibility by reading ‘two

witnesses.’

Barnabas ( 7 ) connects them with the scapegoat.

Possibly

this connection may have seemed to Lk. objectionable.

The miracle (Mk. 11

Mt. 21

of the Withered Fig Tree

may come under this head.

It

has a close resemblance to

(136) parable of the Fig Tree.

Cp

F

IG

.

GOSPELS

carries it a stage further,

ever agrees

with

as

whilst

he

very

steps

in

to

support,

or

explain

by

modifying, some obscure

harsh

statement

omitted

by Lk.

Two important exceptions demand mention :-

(a)

Mk.1525, ‘ I t was the

third

hour and they crucified

him,’ is omitted by Mt. and Lk and con-

14.

Exceptions.

tradicted indirectly

Jn. 19

‘ I t was

about the

hour’ (when Pilate pro.

nounced sentence).

Mk. may have confused

(‘sixth’)

(‘third’).

may be due to a similar confusion.] Or the sentence may be out

of place and should come later, describing the death of Jesus

a s occurring when

was the

lime

when

they crucified

How easily confusion might spring up,

may be seen from the Acts of John

‘when he was hanged

on

the bush of the cross i n the s i x t h

of the day

was over all the land.

First,

‘sixth

might be mistaken for

‘from the’ (or vice versa); then

a numeral would have to

Or

might be

repeated (or dropped) before

In Mk. 15

33,

D,

which

elsewhere gives

in

full, has an unusual symbol

Lk., and

t o be in error, and that Jn. corrected by

what Mt.

and Lk. corrected by omission.

(6)

Mk. 14 30, Before the cock crow

twice

thrice thou shalt

deny

is given by Mt. and Lk. with

omission of

‘twice.

This is remarkable because

‘

twice

enhances the

miraculousness of the predidtion.

May not Mk. be based on

a

Semitic original, which gave the saying thus, Before the cock

crow, twice and thrice’ (=repeatedly, see Job 3329

(1338) accepts

modification of Mt., but with

tion-‘the cock shall not crow, until such time a s thou deny

me thrice

Here Jn. accepts, but‘ improves on, the Synoptic correction of

Mk.,

though perhaps literally correct, does not represent

the spirit of what Jesus said.

[In

I

637

the impossible

thirty

The conclusion is that Mk. seemed to Mt.

111.

D

OUBLE

T

R

A

DI

T

I

O

N

S

.

T h e Double Traditions include what is common to

) Mk.

and Mt.,

)

Mk. and

)

Mt. and Lk. . The last

of

these is so much

fuller than

or

that it may be con-

veniently called

‘

Double Tradition.’

(i.)

and

;

in

to

and

Much of this has been incidentally discussed above,

under the head of the Triple Tradition : and what has

been said there will explain why

Lk.

and Jn. omit Mk.

and

(accounts of the Baptist),

913

(‘Elias

is

come already’),

He calleth for

omission of a long and continuous section of Mk.

(a),

Christ’s walking on the Sea,

the doctrine about

‘

things that defile,’ and

about

‘ t h e children’s crumbs,’

(d),

the feeding of the Four

‘Thousand, ( e ) , acomparison between this and the feeding

of the Five Thousand, and

the dialogue (see 39 n.

)

following the doctrine

of

leaven - may indicate

that

Lk.

knew this section as existing in a separate

tradition, which, for some reason, he did not wish

t o include in his Gospel.

Most

of

it may be said

t o belong to ‘the Doctrine of Bread,’ as taught

in Galilee. Jn. also devotes

a

section of his Gospel to

.a

doctrine of Bread (but of quite a different kind from

concentrating attention on Christ as the Bread.

Lk. also omits (Mk.

the cutting off of hand and

foot,’ and (Mk.

the discussion of the enactments

of Moses concerning divorce-the former, perhaps, as

being liable to literal interpretation, the latter, as being

of date.

The ambitious petition (Mk.

the sons

of

Zebedee, Christ’s rebuke (Mk.

of

Peter as Satan, and the quotation

(Mk.

‘ I will

smite the shepherd,’

L k .

may have omitted,

as

not

tending to edification. I n

the

discourse on ‘ t h e last

day’

L k .

omits a great deal that prevents attention

from being concentrated on the destruction of Jerusalem

as exactly

the predictions

of

Christ; but

especially he omits (Mk.

‘of this hour the Son

knoweth not.’

Attempts have been made, but

in

vain (see

Classical

Review,

T h e parallel

in Mt. can be ascertained by refer-

For the Withering

of

the Fig-Tree (Mk.

11

see 13

n.

18

to prove that

‘sixth hour’ meant 6

A.M.

ence to

GOSPELS

It must be added that,

in this Double Tradition

and (to

a

less extent) in those parts of the Triple

Tradition where

Lk.

makes omissions, Mk. and Mt.

generally agree more closely than where

Lk.

intervenes.

T h e phenomena point to

a

common document occasion-

ally used by

Mk.

and Mt., and, where thus used,

avoided by

Lk.

and also by

T h e Walking on the

Water

is

an exception to

general omission. The

Anointing of Jesus (since

Lk.

has

a

version of it) has

been treated above as part of the Triple Tradition.’

and

in

relation

to

and

is very brief.

The larger portion of it relates

to exorcism,

M k .

(and note

the close agreement between Mk. and

Lk. as to the exorcism of the Legion,’ a name omitted

by Mt. in his account of it). There are also accounts

of Jesus (Mk.

45)

retiring to solitude, and of

people flocking to him from (38) Tyre and Sidon.

A

section of some length attacks the Pharisees, as

(Mk.

12

38-40)

devourers of widows’ houses,’ and prepares the

(Mk.

236) way for

the story of

the widow’s mite.

In the later portions of the Gospel,

Lk. deviates from

Mk.

(as Mt. approximates to

M k . ) ,

returning to similarity in the Preparation for the Pass-

over (Mk.

14

12-16),

but from this point deviating more

and more.

insertion of what may be called the

section,’ is consistent with the prominence given by him

to women and to poverty (see below, 39).

and

or,

The

Double Tradition’

( a )

the Acts of the Lord, ( b ) the Words of

Acts

of

the Lord are con-

fined to

the details of the Tempta-

tion and

the healing of the Centurion’s servant.

gives no detailed account of a Temptation, hut just

it adding (1 13) ‘and the angels were ministering

apparentlyduring the Temptation ; Mt.

says that after the departure of the devil

‘

angels

and

to

unto him

;

Lk.

mentions no ‘angels.’

omits

all

temptation of Jesus,

suggests (1

that ‘angels were always ascending and descend-

ing

on the Son of man,’ and that, in course of time, the eyes of

the disciples would be opened todiscern them.

As regards the healing, some assert that Jn.

does

not refer to the event described by

But if so it can hardly be denied that he,

their

it

in inserting in his Gospel another

case of healing, resembling the former in being performed (

I

)

a t

a distance,

on the child (apparently) of a foreigner, and (3)

near Capernaum.

and Lk. differ irreconcileably.3 Jn.,

Space hardly admits mention of the possiblereasons for

several omissions. Some of these passages

the practical

abrogation of the Levitical Law of meats in Mk.

have seemed to him to point to a later period, such a s that

in

Actslog-16, where Christ abrogated the Law by a special

utterance to Peter. Again in the Doctrine of Bread, while

(Mk.

7

crumbs and

8

leaven are used spiritually

loaves’ and (Mk. 8

‘one loaf’ are used literally and

mixture of the literal and metaphorical may have perplexed Lk

especially if he interpreted the miracle of the Fig-Tree

phorically, and was in doubt a s to the literal or metaphorical

meaning of the Walking on the Water. Some passages he may

also have omitted a5 du licates,

the Feeding of the Four

lhousand.

As regards ‘leaven,’

insertion

‘which is

hypocrisy’), if authentic, is fatal to the authenticityof Mk.

Perhaps the original was simply Beware of leaven,’ and the ex-

planation,

the

was

‘

Beware of

,the leaven of

hypocrisy.

T h e rest was

evangelistic teaching

How

Jesus mean real leaven and

real bread when he could feed his flock with the leaven of heaven

a t his pleasure?’) inserted first as a parenthesis (perhaps about

the

Son

of man or the Son of God), and then transferred to the

text in the first person. The variation of Mt.

ftom Mk.

suggests that the words were not Christ’s.

Jn.

thenarrative of Jesus walking on the Sea but adds

expressions (6

borrowed from Ps.

‘go

to

the

sea and

where they would

which increase

the symbolism of a story describing the helplessness of the

Twelve, when, for a short time, they had left their master. Jn.

omits the statement

(Mk.

and

Mt.)

that Jesus constrained the

disciples to leave him.

The passages referred to in this section will be found in

Rushhrooke’s

Synopticon,

arranged in

order.

D

and

omit Lk.

7

‘Wherefore

neither

thought

I

myself worthy

to

come unto thee,’ thus harmonising Lk. with

Mt.,

who says that the

man did

come to Jesus.

.

GOSPELS

GOSPELS

while correcting both Evangelists in some respects, and especially

in tacitly (448) denying that Jesus ‘marvelled,’ corrects Lk.

more particularly by stating (

I

) that the man came to Jesus

that Jesus

a

word, or promise of healing (3)

the child was healed in t h a t hour,’ and

by

it clear

that the patient was not a servant but a

In the first tbree

points,

Jn. agrees with Mt. in the fourth, he interprets Mt.

in

all,

he differs from Lk.

T h e Words of the Lord are differently arranged

by Mt. and Lk.

Mt. groups sayings according to

their subject matter.

Lk. avows in

his preface

( 1 3 )

an intention to write

in (chronological) order,’ and he often supplies for a

saying a framework indicating the causes and circum-

stances

called it forth. Sometimes, however, he is

manifestly wrong in his chronological arrangement,

,

whenheplaces Christ’s mourning over Jerusalem

(1334 35)

early, and in Galilee, whereas Mt.

(2337-39)

places it in

the Temple at the close of Christ’s

I t was

perhaps on the principle of grouping that Mt. added

to

the shorter version of the Lord’s Prayer the words,

thy will be done, as in heaven so on earth,’ as having

been in part used by Jesus on another occasion (Mt.

other addition, Deliver

us

from the evil

one,’ is not indeed recorded as having been used by

Jesus elsewhere,

it resembles the prayer of Jesus for

his disciples in Jn.

:

keep them

from the

one’

(and cp

Tim.

On

changes, see

L

ORD

’

S

P

RAYER

they adapt the prayer for daily

and indicate that Lk. follows a later version of the

prayer in

his

alterations, but an earlier version in his

omissions.4

exactly

in the Double Tradition

are for the most part of a prophetic or historical char-

acter. Some describe the relations between John the

Baptist and Christ another calls down woe on

another, in language that reminds

of the thoughts,

though not of the words of

thanks God for revealing

t o

babes what He has hidden from the wise and

prudent another pours forth lamentations over doomed

Jerusalem.

Others, such

as,

‘But know this, that if

the goodman,’

and ‘ W h o then is the faithful and

just steward,’ etc., appear to have an ecclesiastical

rather than an individual reference, at all events in their

primary application.

All

these passages were especially

fitted for reading in the services of the Church, and

consequently more likely to have been

soon

committed

to

writing. On the other hand, those sayings which

have most gone home to men’s hearts and have been

most on their lips,

as

being of individual application,

seem to have been

so

early modified by oral tradition

as

to deviate from exact agreement.

Such are, ‘ T h e

mote and the beam

Ask and it shall be given unto

you

Take no thought for the morrow

Fear not

them that kill the body’

‘Whosoever shall confess,’

etc.

He that loveth father or mother more than me,’

etc.

and note, above all, the differences in the Lord’s

Prayer.

As

Lk. approaches the later period of Christ’s

work, he deviates more and more both from Mt. and

Mt. 86 mentions

which may mean ‘child,’ but more

often means servant’ in such a phrase as

etc. See (RV) Mt.

‘my servant’; Acts3

his

(marg. or Child ’).

has repeatedly

47

50)

‘son,’

but finally recurs to Mt. s

word (4

child

liveth (the only instance in which

uses

The reason for

transposition

is

probably to be

in

the last words of the passage, ‘Ye shall not see me, until ye

shall say,

is

t h a t cometh

in the name of the Lord,’

words uttered by the crowd (Lk.

38) welcoming Jesus on his

entrance

into

Lk. probably assumed that the

prediction referred to

utterance, and must, there-

fore, have been made sometime before

before the entrance

into Jerusalem.

3

Cp

I

RV:

‘As may be the will in heaven,

so

The Lord‘s Prayer

(Mt.

69-13

Lk.

112-4).

mentions

(7

‘

servant.

shall he do.’

Cp Lk.

9 23

:

‘If

any one wishes to

come

after

me,

.

.

.

let him take up his cross

daily,’ where Lk. substitutes

the present

for

and

and inserts ‘daily.

in order to adapt the precept to the inculcation of

of

a

from

perhaps because there was a

as well

as

a Galilean tradition of the life of Jesus, and

towards

the close of his history, depended mainly

on

the former.

owing to their length and number

(and perhaps their frequent repetition in varied shapes

by Jesus himself, and by the apostles after

the resurrection), would naturally contain

more variations than are found in the

shorter Words of the Lord.

T h e parable of the Sower,

coming first in order, and having appended to it a

short discourse

of

Jesus (Mk.

that might

seem intended to explain the motive of the parabolic

might naturally find

a

place in the Triple

Tradition.

But this privilege was accorded to no other

parable except that

of

the Vineyard, which partakes

of

the natwe of prophecy.

.

T h e longer discourses of the Double Tradition show traces

o f

a Greek document, often in rhythmical and almost poetic style.

Changes of words such as

for

for

for

for

for

may indicate merely an attempt to render

more exactly a word in the original; but such substitutions as

(Lk.

Spirit’ for (Mt.

‘good

indicate doctrinal pur-

pose. The original of Lk.

13

was perhaps

(as

‘thyspiritis

good,’

R T ]

Lk. appears to have the older

version when he retains (L 1426)

‘hate

his father,’

Mt.

‘love more than

Other variations indicate a corruption or various interpretation

of a Greek original

of course, precluding a still earlier

Mt.

probably

in

text

which he read as

e.,

‘for

two farthings,’ and then he added (‘five before

to complete the sense. Perhaps a desire to make straightforward

sense as well

as

some variation in the

MS.,

may have led Lk. to

substitute

for

in

Mt.

Lk.

This last passage exhibits Lk. as apparently misunderstanding

a

tradition more correctly given by Mt.

I n Mt. it is part of a

late and public denunciation of the Pharisees in Jerusalem in

Lk. it is an early utterance, and in the house of a Pharisee

Christ’s host.

Probably the use of the singular

‘Thou blind Pharisee’), together with the metaphor of the ‘cup

and platter,’ caused Lk. to infer that the speech was delivered

to a Pharisee, in whose house Jesus was dining. The use

of (Lk. 11 39)

(see below,

38) makes it Probable

that

is a late tradition. Other instances of Lk. s altera-

tions are his change of the original and

into the Christian (Lk. 11 49)

Lk. also omits the difficult

I n

Mt.

2334, Jesus

is

represented as saying ‘Wherefore behold

send unto you prophets

. .

.

and

of

them

ye slay

etc.

.

Lk. 1149, ‘Wherefore also

the

Wisdom

God said,

I

unto

them rophets

.

. .

and some

of

them shall they slay etc., omitting ‘crucify.’

Here Lk. seems

to have

in some respects, the original tradition

whereas

Mt.

interpreting the Wisdom of God (cp

I

Cor.

‘Christ the

of

God

to mean Jesus,

it

Also Mt. retains a n a

tradition

which made ‘Zachariah’

of Barachiah

;

Lk. omits the

error.

I n the ‘parables of

the Wedding

Feast, the Talents, and the Hundred Sheep-it may be

said that Mt. lays more stress on the exclusion of those

who might have been expected to be fit, Lk. on the

inclusion of those who might have been expected to b e

unfit.

Thus in the Wedding Feast, Lk. adds

the invitation

of

the maimed,’ etc. Mt. adds

the rejection

Cp P

ARABLES

.

Mk.

(also

Mt. and. Lk.) ‘he will destroy

husband-

men’-{.e., the Jewish nation. The parable of the Sower may

also

be said to predict the history of the Church, its successes

and failures.

‘Hebrew ‘when used in the present article concerning the

original

of the Gospels, means

‘

Hebrew or Aramaic,’

leaving that question open. But see Clue, A. and C. Black,

4

Other instances are

‘over many